Serverless HTTP With Durable Functions

Headache-free asynchronous HTTP shout-outs

Durable Functions enables developers to implement implicit (code-based) and explicit (entity-based) stateful workflows in serverless apps. If you aren’t familiar with this feature, take a moment to read my original article:

Learn how to implement long running stateful workflows in a serverless architecture using Durable Functions, the combination of the open source Durable Task Framework and Azure Functions.

Durable functions rely on a main orchestrator function that coordinates the overall workflow. Orchestrator functions must be deterministic and execute code with no side effects so that the orchestration can be replayed to “fast forward” to its current state. Actions with side effects are wrapped in special activity tasks that act as functions with inputs and outputs and manage things like I/O operations. The first time the workflow executes, the activity is called, and the result evaluated. Subsequent replays use the returned value to ensure the deterministic code path. Until the release of version 2.0, this meant interacting with HTTP endpoints required creating special activity tasks.

As of 2.0, this is no longer the case!

Now, with the introduction of the HTTP Task, it is possible to interact with HTTP endpoints directly from the main orchestration function! The HTTP Task handles most of the interaction for you and returns a simple result. There are some trade-offs. Advantages of using this approach include:

- The task returns a simple result that encapsulates the HTTP content as a string.

- HTTP Tasks support long polling. If the endpoint returns a

202status code, the task will automatically continue to poll the endpoint until it returns a non-202status. - Managed identities are supported out-of-the-box, making it possible to call APIs that require Azure Active Directory tokens. This enables scenarios like restarting VMs and spinning up clusters. In addition,

- Tokens are automatically refreshed when they expire.

- Tokens are never stored in the orchestration state.

- Token acquisition happens automatically.

The disadvantages include:

- HTTP Tasks provide less control relative to wrapping a

HttpClientrequest. - You will experience greater latency with the overhead of the HTTP Task.

- Responses too large to queue are persisted in blob storage resulting in additional overhead and negative performance impact.

- There is no support for streaming, chunking, or binary payloads (i.e. you wouldn’t use this to automate file downloads).

- You have less control over the HTTP headers.

These points are mostly summarized in the official docs; what about a hands-on example to better illustrate its use?

Introducing Durable Search

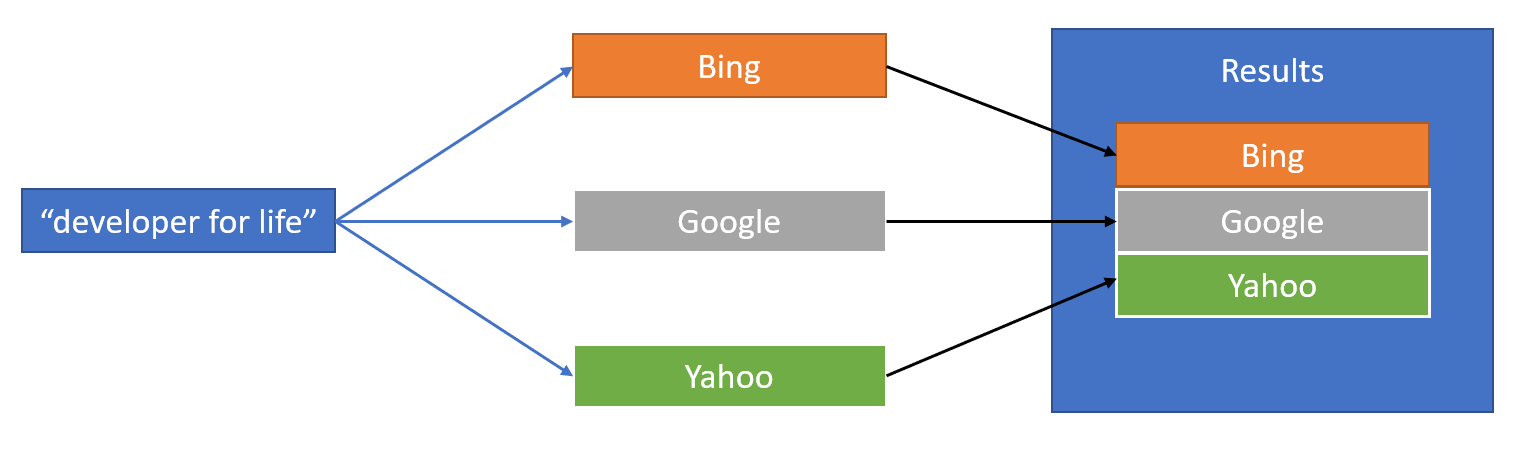

I often use the example of passing a search to multiple sites then aggregating the results when explaining the serverless fan-out/fan-in pattern. It’s time to implement that! I originally wanted to build a site map, but that example is overly complex. In the spirit of keeping things simple, I built “Durable Search”:

This example illustrates a few serverless techniques:

- Serving a single page application (SPA) from an embedded resource that auto-updates to the correct end point

- A serverless function that uses an HTTP Trigger to kick off two orchestrations

- A custom endpoint for querying the status of a long-running orchestration that returns the results when completed

- An orchestration that fans out to multiple search sites and fans-in the results

- A simple orchestration that waits for the longer orchestration to complete by taking advantage of the built-in long-polling feature of HTTP Tasks

The Search Orchestration

The search orchestration is kicked off with an OrchestrationTrigger and returns an array of strings that represent the search results from each site.

[FunctionName(nameof(SearchWorkflow))]

public static async Task<string[]> SearchWorkflow(

[OrchestrationTrigger]IDurableOrchestrationContext context,

ILogger logger)After retrieving the query, the HTTP tasks are kicked off in parallel like this:

var searches = new List<Task<DurableHttpResponse>>()

{

context.CallHttpAsync(HttpMethod.Get,

new Uri($"https://google.com/search?q={search}")),

context.CallHttpAsync(HttpMethod.Get,

new Uri($"https://search.yahoo.com/search?p={search}")),

context.CallHttpAsync(HttpMethod.Get,

new Uri($"https://bing.com/search?q={search}"))

};

var result = await Task.WhenAll(searches);Notice the call signature is as simple as specifying the method and the URL. The responses will contain the result code and the resulting “page” information when successful. The orchestration simply parses the responses and either adds the results or adds a message that something went wrong.

Note: You will still need to handle your own exceptions. If you pass an invalid site, for example (as opposed to just in invalid page with a

404status result) the HTTP Task will throw an exception. For production code you should catch exceptions and handle accordingly (or not catch them and allow the orchestration to fail).

Conceptually, the orchestration looks like this:

Here is the code to build and return the result:

var resultString = new List<string>();

foreach (var response in result)

{

if (response.StatusCode == HttpStatusCode.OK)

{

resultString.Add(response.Content);

}

else

{

resultString.Add("<h1>No Results</h1>");

}

}

return resultString.ToArray();Does it get any easier than that?

The Watcher

Orchestrations automatically expose a set of built-in orchestration APIs for managing and querying the workflow. The status inquiry returns a 202 status code until the orchestration finishes, then it returns a 200 with the results. To demonstrate how the HTTP Task handles long-polling, I wrote a simple “watcher” that issues a status request to the search workflow. The code is straightforward:

var req = context.GetInput<string>();

logger.LogInformation("Starting watcher: {url}", req);

var result = await context.CallHttpAsync(

HttpMethod.Get,

new Uri(req, UriKind.Absolute));

logger.LogInformation("Done watching: {url}", req);

return result.StatusCode;Even though there is just one request, this request will automatically poll the endpoint if it receives a 202 status until it receives something besides 202. It then returns the status code it received.

A Serverless HTTP Function Kick Off

The StartSearch method kicks things off. It is an HTTP-triggered function that has an instance of IDurableClient passed in.

[FunctionName(nameof(StartSearch))]

public static async Task<IActionResult> StartSearch(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get", "post", Route = null)] HttpRequest req,

[DurableClient]IDurableClient client,

ILogger log)After parsing out the query, it does three things:

- Kicks off the search workflow an obtains its unique identifier

- Constructs a status query URL and uses that to kick off the “watcher” workflow

- Returns the unique identifier for the client

var id = await client.StartNewAsync(nameof(SearchWorkflow), (object)query);

// set a workflow that watches the workflow

var queryCheckBase = $"{req.Scheme}://{req.Host.Value}{req.Path.Value}".Replace($"api/{nameof(StartSearch)}", string.Empty);

var checkUrl = $"{queryCheckBase}runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/{id}";

await client.StartNewAsync(nameof(WatchWorkflow), (object)checkUrl);

return new OkObjectResult(id);Tip: when you pass a string as the second parameter to

StartNewAsyncthe client expects that to be the unique identifier. If you are trying to pass a string as a parameter and expect the workflow to be assigned a unique guid instead, simply cast the string parameter toobjectas shown.

At this stage all the required elements are in place. I could write a client that understands the orchestration endpoints and queries the status directly, but I chose to wrap that logic in another function.

The Status Endpoint

The status endpoint is another HTTP-triggered function that takes the id of the workflow as a parameter.

[FunctionName(nameof(GetResult))]

public static async Task<IActionResult> GetResult(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get", "post", Route = null)] HttpRequest req,

[DurableClient]IDurableClient client,

ILogger logger)It uses the IDurableClient instance to request the status of the workflow, then returns a status and/or result based on a few conditions:

- “Not found” (

404) is returned if the workflow doesn’t exist - If the orchestration ended for a reason other than success, a “bad request” (

400) result is returned - After the orchestration completes, an “OK” (

200) status is returned and the results are passed back as an HTML page with a horizontal rule separating providers - Otherwise, an “accepted” (

202) result is returned, indicating the workflow is still in process

Here is the implementation:

var jobStatus = await client.GetStatusAsync(idString);

if (jobStatus == null)

{

return new NotFoundResult();

}

if (jobStatus.RuntimeStatus == OrchestrationRuntimeStatus.Canceled

|| jobStatus.RuntimeStatus == OrchestrationRuntimeStatus.Failed

|| jobStatus.RuntimeStatus == OrchestrationRuntimeStatus.Terminated)

{

return new BadRequestObjectResult("Orchestration failed.");

}

if (jobStatus.RuntimeStatus == OrchestrationRuntimeStatus.Completed)

{

var result = jobStatus.Output.ToObject<string[]>();

var response = new ContentResult

{

Content = string.Join("<hr/>", result),

ContentType = "text/html"

};

return response;

}

return new StatusCodeResult((int)HttpStatusCode.Accepted);Now we have the full workflow!

A Simple Client

To make it easier to interact with the workflow, I created a simple Single Page Application that I embed in the assembly as index.html. This lets me use intelligent code completion, syntax highlighting and formatting when I build it but makes it easily packaged and shipped.

The code waits for you to enter some text and click a button. After the button is clicked, the fetch API is used to hit the function endpoint that kicks off the workflow. The id is saved and used to query the results API. If the result is a 202, the request is repeated every 300ms until a valid status code is received. A 200 means the request is ready and the result is stuffed into a div element.

I added a Content Security Policy (CSP) that prevents any of the sites from pulling in embeds, fonts, stylesheets, or JavaScript. This means the results are not styled. If you want to see them styled with embeds (i.e. when the result returns images and/or videos) simply remove the meta tag from index.html that specifies the security policy. You can learn more about the CSP here:

A Content Security Policy (CSP) helps prevent a variety of attacks on your site. This article describes how to implement one for a static website when you don't control the headers.

The following code is executed only once per process to retrieve the embedded resource:

var assembly = Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly();

var resource = $"{assembly.GetName().Name}.index.html";

using (var stream = assembly.GetManifestResourceStream(resource))

{

using (var reader = new StreamReader(stream))

{

return reader.ReadToEnd();

}

}The base API URL is specified like this:

const url = "{baseUrl}";An HTTP-triggered function is used to return the page. It dynamically retrieves the base URL from the request and uses it to update the returned page.

var url = $"{req.Scheme}://{req.Host.Value}{req.Path.Value}".Replace("Search", string.Empty);

var contentResult = new ContentResult

{

Content = SearchContent.Replace(BaseUrl, url),

ContentType = "text/html"

};

return contentResult;Now everything is ready to run!

The Finished App

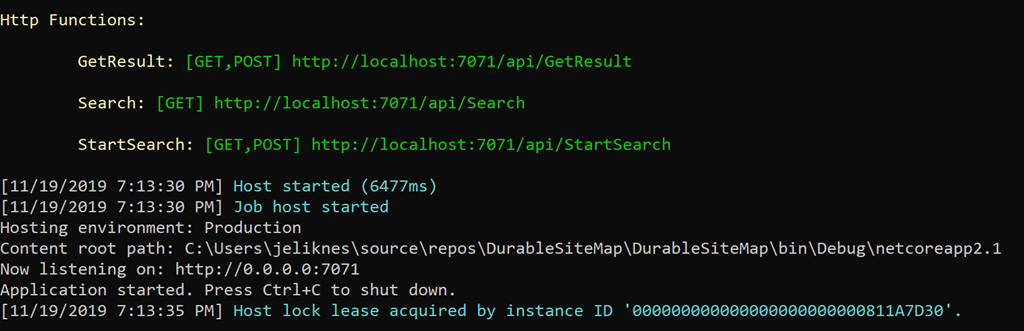

I tested the app locally with the storage emulator running. The project spins up and reveals the HTTP endpoints:

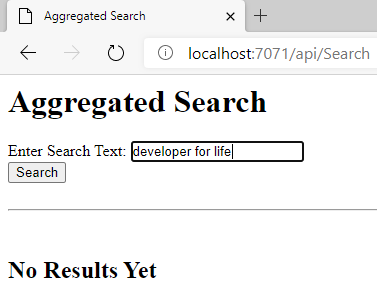

The search endpoint is the one I’m interested in, so I open that in my browser and the single page app is served:

After a delay of a few seconds as the results are aggregated …

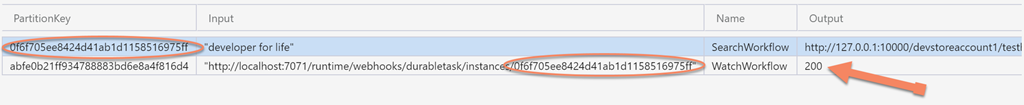

The results return and the workflow completes. I can then look at the Azure storage tables that Durable Functions uses “behind the scenes” and see the successfully completed workflow. Notice the search workflow has the query set for input and the output points to a “large message” that contains the string array of results. The “watcher” workflow has the orchestration status URL for input and the final status (“OK” - 200) for output.

That’s a wrap!

Conclusion

The new Durable Functions framework has many new features. Hopefully this gives you an idea and insight into managing HTTP APIs, both as a consumer and a producer. Be sure to visit the official documentation for the latest information. As always, I welcome your discussions, comments, suggestions and feedback below.

Regards,

Related articles:

- Azure Cosmos DB With EF Core on Blazor Server (Azure)

- Deep Data Dive with Kusto for Azure Data Explorer and Log Analytics (Azure)

- Introducing Durable Entities for Serverless State (Azure Functions)

- Moving From Lambda ƛ to Azure Functions <⚡> (Azure Functions)

- Stateful Serverless: Long-Running Workflows with Durable Functions (Durable Functions)

- The Year of Angular on .NET Core, WebAssembly, and Blazor: 2019 in Review (Azure)