Run EF Core Queries on SQL Server From Blazor WebAssembly

...or any other EF Core provider, for that matter

It started with a simple idea.

💡 What if I could write a LINQ query on a client the same way I would on a server, and execute it remotely with minimal configuration, setup, ritual and ceremony?

It’s not a new idea. The idea sparks important questions such as:

- How do I prevent users from writing dangerous queries that impact performance or return excessive rows?

- How do I keep users from calling methods that have negative side effects?

- How do I account for differences between database providers?

What if you could write fewer than five lines of configuration code and have something like this work seamlessly … from a Xamarin or Blazor WebAssembly client?

var list = await DbClientContext<ThingContext>.Query(context => context.Things)

.Where(t => t.IsActive == ActiveFlag &&

EF.Functions.Like(t.Name, $"%{nameFilter}%"))

.OrderBy(t => EF.Property<DateTime>(t, nameof(Thing.Created)))

.ExecuteRemote()

.ToListAsync();

The experience of working with data from .NET applications is extremely important to me. OK, it’s technically my job. I built many production line of business applications in C# over almost two decades and have many unique experiences to learn from. A very common problem to solve for any application is how the various clients will connect to the source of truth to query, mutate, and synchronize data. Most operations are straightforward to implement using protocols like REST or gRPC. The surface area of an insert, update, or delete operation is relatively small, even when applying business rules and validation, compared to queries. The query scenario is more complex. There are options to make your life easier (like Swagger and the OpenAPI specification) and you can tap into existing solutions like OData or GraphQL, but those often require significant setup and impose limitations.

To solve problems like this, I like to work backwards from the solution. I mocked some code that represents what I think a quality experience looks like, then set out to make it a reality. I chose to use Entity Framework Core not only because it is a product I help manage, but because it has successfully encountered and solved many problems and edge cases already. Instead of figuring out the database pieces, I can just figure out how to hand off my query to EF Core and let it take care of the rest. I spun up a “pet project” with the intent to learn as much as possible about maintaining an open source project. Even if I weren’t able to solve the problem, I knew I would learn much.

The Solution

The solution involves just two lines of code to setup and enable running queries remotely. Caveat: this code is alpha. There are a few things I know need to be done and likely a lot of things to be completed that I don’t know about yet. I haven’t focused on performance or rough edges. This is what’s possible for a Blazor WebAssembly project with an ASP.NET Core API backend:

- Install the middleware on the server (you might need

-prereleaseand-Versionoptions depending on when you read this)Install-Package ExpressionPowerTools.Serialization.EFCore.AspNetCore - Add the line of code to

Startup.csto configure the middlewareapp.UseEndpoints(endpoints => { endpoints.MapPowerToolsEFCore<ThingContext>(); endpoints.MapRazorPages(); }); - Install the client on the Blazor WebAssembly project

Install-Package ExpressionPowerTools.Serialization.EFCore.Http - Add the line of code to

Program.csto configure the clientbuilder.Services.AddExpressionPowerToolsEFCore(new Uri(builder.HostEnvironment.BaseAddress));

With that, you’re ready. Assuming you have a DbContext named ThingContext on the server connected to SQLite, SQL Server, MySQL, PostgreSQL or Oracle, you can run queries as if you’re on the server. As I wrote earlier, you can…

var list = await DbClientContext<ThingContext>.Query(context => context.Things)

.Where(t => t.IsActive == ActiveFlag &&

EF.Functions.Like(t.Name, $"%{nameFilter}%"))

.OrderBy(t => EF.Property<DateTime>(t, nameof(Thing.Created)))

.ExecuteRemote()

.ToListAsync();

Notice that I’m using EF Core extension methods and functions as part of the query! Although I haven’t tested it, this should also work perfectly fine with Azure Cosmos DB. It was a very exciting moment to see the Sample project run and return results the first time. I plan to build a more involved sample based on the reference contacts app and MVVM. The rest of this post is about the journey. I won’t cover everything, but it has been an amazing journey the past several months.

Here are just a few things I learned during this project:

- What Language Integrated Queries LINQ really are and how they are composed with extension methods and expressions

- Expression trees, inside and out

- How the .NET type system works

- How to take an incredibly complex type and reconstruct it on demand

- How to reverse engineer the XML documentation comments bizarre key format and build an algorithm to map members to XML comments

- How to uniquely identify members like fields, properties, methods and constructors

- How to build ASP.NET Core middleware using endpoint routing

- How to build a reusable HTTP-based client using IHttpClientFactory

- How to apply a common set of style guidelines across projects using StyleCop and .editorConfig

- How to use xUnit.net for unit tests

- How to adopt a versioning strategy using tools like Nerdbank GitVersion

- How to apply common project attributes

- How to automate the generation of useful API documentation through XML comments

- How to automate builds, tests, and NuGet packaging with GitHub actions

Explore the Expression Power Tools on GitHub

Let the journey begin!

Comparisons

The first thing I had to tackle is verification. If I write a query on the client, how do I verify it is correctly reassembled on the server? It turns out that comparing expressions is not straightforward. I came across a few libraries in my research but ultimately decided to build a comparison engine on my own. If nothing else, this forced me to dig deep into the internals of expressions.

⭐ Tip: I wish I knew this earlier, but ultimately I found two resources that helped me tremendously with understanding expressions. The first is a single class in the .NET Core source. Expressions provide a surprisingly detailed representation when you call

ToString()and that is due to theExpressionStringBuilderclass. Because it must deal with every expression type, it is a single source to understand how to navigate and read parts of expressions. The second resource is the EF Core source code. It takes a while to understand but I consider the code in the EFCore/Query subfolder to be a graduate course curriculum in expressionology.

I chose to go with a recursive approach. I started with the simplest case: the ConstantExpression. This expression holds a value and the value’s type (in case it is null.) The logic to compare two constant expressions looks like this:

- Do they share the same reference? If yes, they are equivalent. If not…

- Is one or the other null? Then they are not equivalent

- The types of the expressions must be equal to each other

- If the type of the expression is another expression, apply the equivalency check to the values

- Otherwise, try to do a value comparison

It turns out that answering the question, “are these two values equal” without context can be difficult. I settled on a “good enough” approach that looks like this (ValuesAreEquivalent in ExpressionEquivalency.cs):

- Reference equals

- If values are types, compare types

- If values are expressions, compare expressions

- If values are

MemberInfo(properties, fields, methods, or constructors), compare members - If values are dictionaries, compare the dictionary keys and values

- If values implement

IEquatablethen cast and invoke - If values implement

IComparablethen cast and invoke - If values are exceptions, compare the types and messages

- If values are enumerable, enumerate and compare recursively (except for strings, which are enumerable as characters)

- Last resort:

Object.Equals

After doing this for several expressions, I realized it is possible to encapsulate the rules in expressions themselves. For example, this is true:

public static Expression<Func<T, T, bool>> True<T>()

where T : Expression => (_, __) => true;

For combing fragments of rules, here’s a logical OR implementation:

public static Expression<Func<T, T, bool>> Or<T>(

this Expression<Func<T, T, bool>> left,

Expression<Func<T, T, bool>> right)

where T : Expression

{

var expr = Expression.Invoke(right, left.Parameters);

return Expression.Lambda<Func<T, T, bool>>(

Expression.OrElse(left.Body, expr), left.Parameters);

}

The left expression already exists, so it has parameters that point to the expressions to compare. To pass the parameters to the right expression, we create an invocation. This can then be combined with the left expression using the Expression.OrElse method. The trick is that somewhere at the top of the tree there are parameters set with the expressions, so these are passed down as the tree is built. You can utilize existing method calls, like this example:

public static Expression<Func<T, T, bool>> ExpressionsMustBeEquivalent<T>(

Func<T, Expression> member)

where T : Expression => (s, t) =>

eq.AreEquivalent(member(s), member(t));

And build combinations:

public static Expression<Func<T, T, bool>> AndExpressionsMustBeEquivalent<T>(

this Expression<Func<T, T, bool>> rule,

Func<T, Expression> member)

where T : Expression => And(rule, ExpressionsMustBeEquivalent(member));

Why bother? Because of readability. Here is the rule for lambda expressions:

public static Expression<Func<LambdaExpression, LambdaExpression, bool>>

DefaultLambdaRules { get; } =

rules.MembersMustMatch<LambdaExpression>(e => e.Name)

.AndMembersMustMatch(e => e.TailCall)

.AndExpressionsMustBeEquivalent(e => e.Body);

It should be fairly clear! The rules are all implemented in DefaultComparisonRules.cs. I’ll talk about “similarity” in a minute.

Compiled expressions vs. “raw code”? What about performance? I haven’t run any performance benchmarks yet, but compiled expressions perform exceptionally well. I will eventually write some benchmarks, but in case it becomes a problem down the line, I maintain a separate rules implementation that is direct code. Ultimately, I’d probably include logic to emit Intermediate Language (IL) from the expressions on frameworks that support it and fallback to code on those that don’t.

Again, this was a fun project to explore expressions and use them.

Sidebar: Lambdas in APIs

Expressions are extremely helpful for building APIs that infer information from strongly typed references. For example, I wrote Ensure.NotNull to validate parameters the old-fashioned, pre “nullable types” way. It’s not necessary because new keywords and attributes like CallerMemberName and nameof can resolve references at compile time, but it was a fun learning experience. Here’s the code to extract the value and name of a parameter using an expression like this: () => parameter:

// extract the name

public static string MemberName<T>(

this Expression<Func<T>> expr) =>

((MemberExpression)expr.Body).Member.Name;

// compile and check the value

public static void NotNull<T>(Expression<Func<T>> value)

{

var fn = value.Compile();

if (fn() == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException(value.MemberName());

}

}

A more interesting example of this came when I needed a way to identify methods, constructors, properties and fields for the permissions engine. Instead of forcing you to use reflection to find the member, I wanted to provide flexible options, like:

// type and name

var member = helper.OfType<MyClass>().WithName(nameof(MyClass.Property));

// but what if there are multiple overloads, as with a method? How about a template:

var member = helper<MyClass>(mc => { mc.DoStuff(1, 2); }); // never called

More on that later. After tackling equivalency, I added a few extension methods and arrived at my first milestone: verifying that expressions match.

[Fact]

public void GivenIEquatableImplementedAndTrueThenAreEquivalentShouldReturnTrue()

{

var source = new IdType().AsConstantExpression();

var target = new IdType

{

Id = ((IdType)source.Value).Id,

IdVal = ((IdType)source.Value).IdVal

}.AsConstantExpression();

Assert.True(eq.AreEquivalent(source, target));

}

There was a problem, though. For some reason, comparing a complex expression based on a query was failing. And I realized it’s not always practical to compare the full expression. Let’s assume I’m unit testing a view model and want to verify it applies the Skip property to the expression. How can I verify that Skip(Skip) is a part of the expression without having to compare the entire expression?

Unroll the Expression Tree

The first step was to have a consistent way to parse the tree. Expression trees can be very deep and complex, so I wrote ExpressionEnumerator and related extension methods to easily parse the tree. For example, I can extract all of the constants like this:

var constants = expr.AsEnumerable().OfType<ConstantExpression>().ToList();

Even better, if I want to examine the integers in the tree:

var integers = expr.AsEnumerable().ConstantsOfType<int>().ToList();

This let me implement IsPartOf so I can assert:

Assert.True(exprChild.IsPartOf(exprParent));

The child might be the “take” portion of the expression while the parent is the whole query. This would fail with equivalency because the parameters won’t match. Take(10) is a method call with two parameters: the source entities to take from (this is what the extension method starts with), and the number of entities to take. On the other hand, Where(t => t.IsActive).Take(10) has the same value parameter (10) but the other parameter is a method call (Where) that must be resolved to serve as input. Recognizing this, I built a similarity system to make relative comparisons. The IsPartOf implementation unrolls the parent tree and looks for any expressions that are similar:

return targetTree.Any(t => AreSimilar(source, t));

How is similarity implemented?

Similarity

When the Take method is encountered, the following rule is applied:

public static Expression<Func<MethodCallExpression, MethodCallExpression, bool>>

DefaultMethodSimilarities { get; } =

rules.TypesMustBeSimilar<MethodCallExpression>()

.AndTypesMustBeSimilar(e => e.Method.DeclaringType)

.AndMembersMustMatch(e => e.Method.Name)

.AndMembersMustMatch(e => e.Arguments.Count)

.AndIf(

condition: (s, t) => s.Object != null,

rules.SourceMustBePartofTarget<MethodCallExpression>(

e => e.Object))

.And((s, t) => ExpressionSimilarity.ArgumentsAreSimilar(

s.Arguments,

t.Arguments));

The method must be the same, but arguments only need to be similar. Ultimately we end up with the rule for constants. The rule eventually uses equivalency to compare the values, but there is a concession in the code:

var type = source.GetType();

if (type.IsGenericType && type.GetGenericTypeDefinition() == typeof(EnumerableQuery<>))

{

var targetType = target.GetType();

return targetType.IsGenericType &&

targetType.GetGenericTypeDefinition() == typeof(EnumerableQuery<>) &&

!targetType.GenericTypeArguments.Except(type.GenericTypeArguments).Any();

}

This basically checks to make sure the query is of the same type. This allows the expression to match independent of the implementation. Because we only need the parameter to be “a part of”, the fragment with just Take is compared to the Where method, which has its own parameter that is a queryable, and those arguments will match.

[Fact]

public void GivenTargetWithSimilarQueryPartsWhenIsPartOfCalledThenShouldReturnTrue()

{

var target = query.Skip(2).Take(3);

var source = target.CreateQueryTemplate().Take(3);

Assert.True(eq.IsPartOf(source.Expression, target.Expression));

}

That’s a ✅ passing test.

Hosts and Providers

In building the core library I decided it was important to be able to take a snapshot of a query when executed (useful for validating tests) and mutate a query (useful for doing things like security checks). I imagined I would have a set of rules to apply against an expression to transform it into compliance. It turns out when I finally implemented the serialization, I was able to apply rules as I rebuilt the expression. That’s fine because the capability is still there. I wrote about this at length in Inspect and Mutate IQueryable Expression Trees. The library provides a generic QueryHost that allows you to track additional metadata about a query. I use it in my solution to track the original EF Core source so I can route the request appropriately. There are two built-in providers as well.

The QuerySnapshotProvider exposes a callback that is invoked right before a query runs. You can snapshot for logs or even inspect it and throw an error to prevent execution. The QueryInterceptingProvider goes one step further and allows you to transform the query (for example, strip out unwanted method calls or add business logic automatically).

A query is nothing more than a wrapper around an expression tree that provides a GetEnumerator() method for iterating the result. The provider is what makes it happen. The provider has an Execute(Expression) method for compiling and running the expression tree against the source. This is where you can tap into the pipeline. There is also a CreateQuery(Expression) method that turns an expression into a queryable. This happens during the course of processing existing expression trees that project to other types. If you write a query like this:

var query = things.Select(t => new SubThing(t.Id));

The query starts out as an IQueryable<Thing> but ends up as an IQueryable<SubThing>. When the projection is encountered, the provider will create a query with the new type for the subtree. Another place this is useful is in a serialization pipeline. I serialize the expression tree and use CreateQuery to turn it back in the query that EF Core runs.

Dependency Injection

It quickly became evident I needed a dependency injection system. Instead of taking a dependency on an external provider, I decided to implement my own. Again, this was mostly a learning experience, but I also wanted to minimize dependencies and make it more self-contained so that overriding defaults is the exception, not the null. The system allows for registering types that are implemented on the fly, and singletons. I may have made a bad decision when I chose to implement the solution as a static host, but it was the easiest way to make it globally available. The caveat is that I have to run tests in single-threaded to avoid conflicts with the services mutating as part of test runs. I am considering refactoring to allow partitions as part of Issue #20 but for now I haven’t encountered major issues outside of testing.

The ServiceHost contains a static reference to a Services instance. The services are a simple dictionary for mapping types and singletons. To avoid conflicts I chose to create a “registration window” for registering services that doesn’t allow mutations after. The goal is not to allow users to override services, but to easily define them internally and provide a way to mock or substitute for tests. This is why the “service domain” concept is appealing to me. By default, the services are loaded from the static constructor. You can call Initialize to register overrides. This passes back an interface with the registration methods that is can be chained to register in one pass:

ServiceHost.Initialize(register =>

{

var evaluator = new ExpressionEvaluator();

register.RegisterSingleton(Services)

.RegisterSingleton(DefaultRules)

.RegisterSingleton<IExpressionEvaluator>(evaluator)

.Register<IExpressionEnumerator, ExpressionEnumerator>()

.RegisterGeneric(typeof(IQuerySnapshotHost<>), typeof(QuerySnapshotHost<>))

.RegisterGeneric(typeof(IQueryHost<,>), typeof(QueryHost<,>))

.RegisterGeneric(typeof(IQueryInterceptingProvider<>), typeof(QueryInterceptingProvider<>))

.RegisterGeneric(typeof(IQuerySnapshotProvider<>), typeof(QuerySnapshotProvider<>));

});

The service exposes a GetService and a recommended GetLazyService method. The latter allows code to reference the service but not actually implement it until it is used to potential avoid conflicts during registration.

Satellite Assemblies

When I started the second project for serialization, I immediately realized I needed a way for dependent assemblies to register their own services. I decided the easiest way is to simply implement an interface. When ServiceHost is initialized, it scans the app domain assemblies for types that implement IDependentServiceRegistration and calls RegisterDefaultServices. By convention, you’ll see a file in the root of my projects named Registration that implements the interface to register dependencies. I also added an AfterRegistered hook. This allows scenarios such as initializing configuration and default options after the services are registered. For example, the ASP.NET Core middleware uses this to allow EF Core extension methods:

public void AfterRegistered()

{

ServiceHost.GetService<IRulesConfiguration>()

.RuleForType(typeof(Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.EF))

.RuleForType(typeof(Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.DbFunctionsExtensions));

}

But now I’m getting ahead of myself. Before we can talk about serialization rules, we should talk about serialization!

Serialization

As with everything else, I took a step-by-step test-driven approach and started with the easiest option: ConstantExpression. There are just two parts: a value and a type. What could possibly go wrong?

It turns out that types aren’t as easy as they may seem. You can’t simply save a type name and easily recreate it. Simple types are fine, but types that have generic parameters are another story. I built a system that seems to work, but I also am spiking a different solution that shows promise. I’ll cover what’s there now in a moment. The strategy I decided to go with was to create some complementary classes to expressions that are easy to serialize. The first class is the base class for all of these building blocks: SerializableExpression. It contains just one thing: the ExpressionType. This is exactly what’s needed to construct a new expression. Some types map one-to-one, such as Constant. Other types like Add and And both belong to BinaryExpression.

The unit of serialization is the Constant class. This holds a type for the constant, a value, and a type for the value. Why the difference? It turns out you can potentially have a constant with an interface type. The value obviously can’t be an interface but must be an implementation of the interface. The value type allows me to deserialize the value while the constant type enables recreating the expression. This is done recursively in the ConstantSerializer. It’s recursive because the value of the constant can be another expression.

You’ll notice that the serialization uses System.Text.Json. I may refactor it later to an encoded stream that can be transported via other methods, but for now this was the simplest approach. I wanted to minimize dependencies on third-party libraries and take advantage of the performance of the library. Let’s talk types.

Types

To capture types, I came up with a hierarchical set of primitives named SerializableType with a handful of properties (don’t look for it in the code, it’s gone because I’ve already refactored it):

- FullTypeName was a human-readable, friendly look at the full hierarchy including generic type arguments

- TypeName was the machine-readable name used to generate the type

- GenericTypeArguments were used to find the right generic type or close the generic type as needed

During serialization, the SerializationState maintains a list of types. Unless the option is disabled, types are compressed. This means their index is swapped for their full name. Consider a list like this:

0 IQueryProvider<T>

0->0 - T

1 IQueryHost<T, IQueryProvider<T>>

1->0 - T

1->1 - IQueryProvider<T>

1->1->0 -- T

2 CustomProvider<T>

2->0 - T

3 QueryHost<T, CustomProvider<T>>

3->0 - T

3->1 - CustomProvider<T>

3->1->0 -- T

4 T

5 QueryHost<string, CustomProvider<string>>

5->0 - System.String

5->1 - CustomProvider<string>

5->1->0 -- System.String

6 CustomProvider<string>

6->0 - System.String

7 System.String

After compression, the list looks like this:

0 IQueryProvider<T>

0->0 - ^4

1 IQueryHost<T, IQueryProvider<T>>

1->0 - ^4

1->1 - ^0

2 CustomProvider<T>

2->0 - ^4

3 QueryHost<T, CustomProvider<T>>

3->0 - ^4

3->1 ^2

4 T

5 QueryHost<string, CustomProvider<string>>

5->0 - ^7

5->1 - ^6

5->1->0 -- ^7

6 CustomProvider<string>

6->0 ^7

7 System.String

This is easily compressed and decompressed.

The New Type System

It was frustrating me to have so much overhead for types and a different system to serialize types verse other members like constructors. I realized the XML doc comments already have a workable algorithm to uniquely identify types. So, I reverse engineered the algorithm to implement a new member management system. Now all members are represented as strings. Base types map directly to nodes in XML comments. For example:

Here is the representation of a generic type.

typeof(IThing<,,>)

"T:ExpressionPowerTools.Core.Tests.MemberAdapterTests+IThing`3"

The single back tick means it’s a type with three generic parameters. This is how the base system works. I extended it to allow me to reference closed types as well, like this:

typeof(IThing<ThingImplementation, IComparable<ThingImplementation>, char>)

"T:ExpressionPowerTools.Core.Tests.MemberAdapterTests+IThing{ExpressionPowerTools.Core.Tests.MemberAdapterTests+ThingImplementation,System.IComparable{ExpressionPowerTools.Core.Tests.MemberAdapterTests+ThingImplementation},System.Char}"

Notice that closed types may be nested. Methods with generic method parameters get two back ticks. Here’s a dummy method to demonstrate:

public static TResult Result<T, TResult>(T entity, string name) => default;

Representation:

"M:ExpressionPowerTools.Core.Tests.MemberAdapterTests.Result``2(``0,System.String)"

The two back ticks mean there are two closed types. In the parameters, the 0 refers to the first closure. So where is the second? If it’s not in the parameters, it’s the return type. Knowing that, I can “close” the method:

Expression<Func<int>> closedResultExpr = () => Result<MemberAdapterTests, int>(

new MemberAdapterTests(),

nameof(indexer));

And serialize it like this:

"M:ExpressionPowerTools.Core.Tests.MemberAdapterTests.Result{System.Int32}(ExpressionPowerTools.Core.Tests.MemberAdapterTests,System.String)"

If you want to have fun seeing how I stretched the limits of my ability to figure out an algorithm, check out the member adapter. I plan to add extension methods to make it easier for others to use, for example when generating documentation. I’m confident I have some optimization opportunity there. I added some cache and improved performance 50% but my spike to change string manipulation to use Span<T> did not perform better so I pulled it to minimize dependencies.

Members

Members are tricky to serialize. Members include types, methods, constructors, properties, and fields. It’s fairly straightforward to ask for ToString() on the System.String type, but what if you have IMyType<T, TImpl> where TImpl : IOther<T> and then a method that is TImpl SetImplementation<Z>(Z input) where Z : IRoutable<T>? It can get very complex quickly. The initialize approach I settled on before I figured out the universal method system was to create unique building blocks per member, then expose a “key” that is essentially everything unique about that member, combined into a string. That way I can verify I’ve deserialized to the right member and use properties to build implementations of generic types. Consider a constructor:

[Serializable]

public class Ctor : MemberBase

{

public Ctor()

{

}

public Ctor(ConstructorInfo info)

{

DeclaringType = SerializeType(info.DeclaringType);

MemberValueType = DeclaringType;

ReflectedType = SerializeType(info.ReflectedType);

IsStatic = info.IsStatic;

Name = $"{DeclaringType.FullTypeName}()";

Parameters = info.GetParameters().Select(

p => new

{

p.Name,

Type = SerializeType(p.ParameterType),

})

.ToDictionary(p => p.Name, p => p.Type);

}

public override int MemberType

{

get => (int)MemberTypes.Constructor;

set { }

}

public bool IsStatic { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public Dictionary<string, SerializableType> Parameters { get; set; }

= new Dictionary<string, SerializableType>();

}

It contains the parent type, the static flag, and parameters. The “key” for this looks like;

public override string CalculateKey() =>

string.Join(

",",

new[] { "C:" }

.Union(Parameters.Keys.ToArray())

.Union(Parameters.Values.Select(p =>

GetFullNameOfType(p)).ToArray())

.Union(new[]

{

GetFullNameOfType(ReflectedType),

IsStatic.ToString(),

GetFullNameOfType(DeclaringType),

Name,

}));

To deserialize, I found the parent type, applied any type arguments needed, then search constructors to find a match. I’m currently working on a new approach that may simplify things in the future.

Now I just use the new universal string system I explained earlier. So much easier!

Security

The biggest concern with an approach to serializing queries is security. A malicious user could issue a purposefully complex query designed to hinder performance. The attacker may try to invoke methods on the server that involve file I/O. To prevent

this, I built an opt-in security model. The queries can access fields and properties but by default are not authorized to use methods or constructors. You can further ban entire types you don’t want to expose. The rule builder is fluent and hierarchical. For example, the default rules ensure you can query and enumerate, manipulate strings and dates, and use the math library. The only thing allowed on the base object class is ToString().

rules.RuleForType(typeof(Math))

.RuleForType(typeof(Enumerable))

.RuleForType(typeof(Queryable))

.RuleForType<string>()

.RuleForType<DateTime>()

.RuleForMethod(

selector =>

selector.ByNameForType<MethodInfo, object>(

nameof(object.ToString)));

The EF Core libraries also allow some EF Core extension methods:

public void AfterRegistered()

{

ServiceHost.GetService<IRulesConfiguration>()

.RuleForType(typeof(Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.EF))

.RuleForType(typeof(Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.DbFunctionsExtensions));

}

For performance, rules are cached as they are evaluated. I suspect this is the area I’ll spend the most time on to take this to production. Security is incredibly important, especially hardening the application to prevent access to types that expose sensitive data. I am thinking about denying properties and fields by default as well, then allowing assembly-level config so you can opt-in your model project, etc.

The Selector

As I mentioned earlier, finding the actual definition of a member can be hard. For this reason, I build a selector to make it easier to define types. If you want all overloads of a method to be available, you can use this convention:

SelectMember<MethodInfo>(selectMethod => selectMethod.ByNameForType<MethodInfo, SelectorTests>

(nameof(SelectorMethod)));

If you want a specific member, you can use a resolver template. This mimics a call but is never actually executed and only used to find the member. Here’s an example that resolves a specific constructor overload:

SelectMember<ConstructorInfo>(selectCtor => selectCtor.ByResolver<ConstructorInfo, Nested>

(n => new Nested(nameof(Nested).GetHashCode())));

That will find the constructor that takes an integer parameter. This is done, of course, using expressions. The lambda expression is “unrolled” using the enumerable extension, then the relevant expression that references the member is extracted.

private static void Resolve<T, TTarget>(

MemberSelector<T> memberSelector,

Expression expr)

where T : MemberInfo

{

if (typeof(T) == typeof(MethodInfo))

{

var methodCall = expr.AsEnumerable()

.OfType<MethodCallExpression>().FirstOrDefault();

memberSelector.Member = new[] { methodCall.Method as T };

}

else if (typeof(T) == typeof(ConstructorInfo))

{

var ctor = expr.AsEnumerable()

.OfType<NewExpression>().FirstOrDefault();

memberSelector.Member = new[] { ctor.Constructor as T };

}

else

{

var memberAccess = expr.AsEnumerable()

.OfType<MemberExpression>().FirstOrDefault();

memberSelector.Member = new[] { memberAccess.Member as T };

}

}

At this point I hit my goal and was able to successfully serialize, deserialize, and execute queries. However, when it came to testing across machines, something interesting came up. An expression like this would invariably fail:

var filterActive = true;

var activeFilter = false;

var skip = 5;

var query = things.Where(t =>

(filterActive && t.IsActive == activeFilter) || !filterActive)

.Skip(skip)

.Take(10);

Can you spot the challenge?

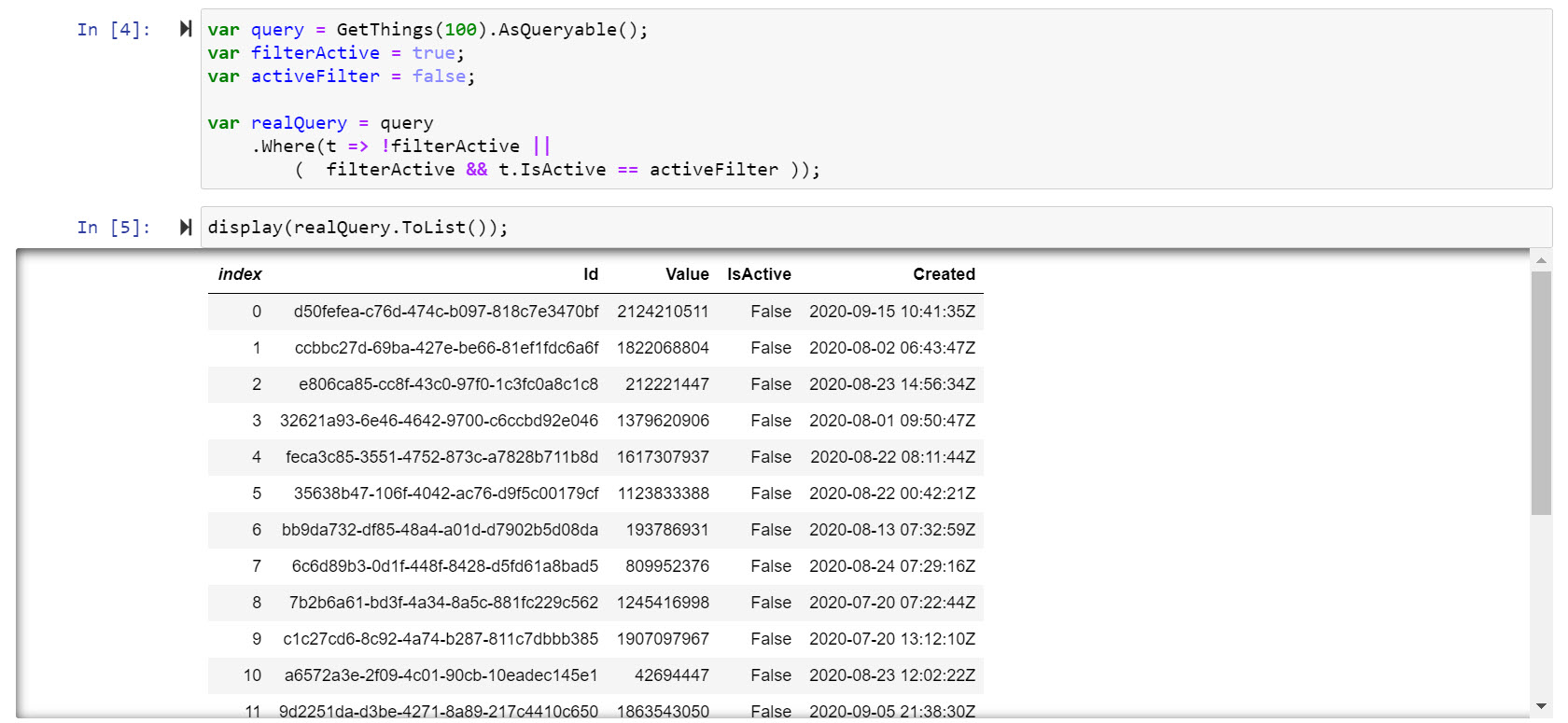

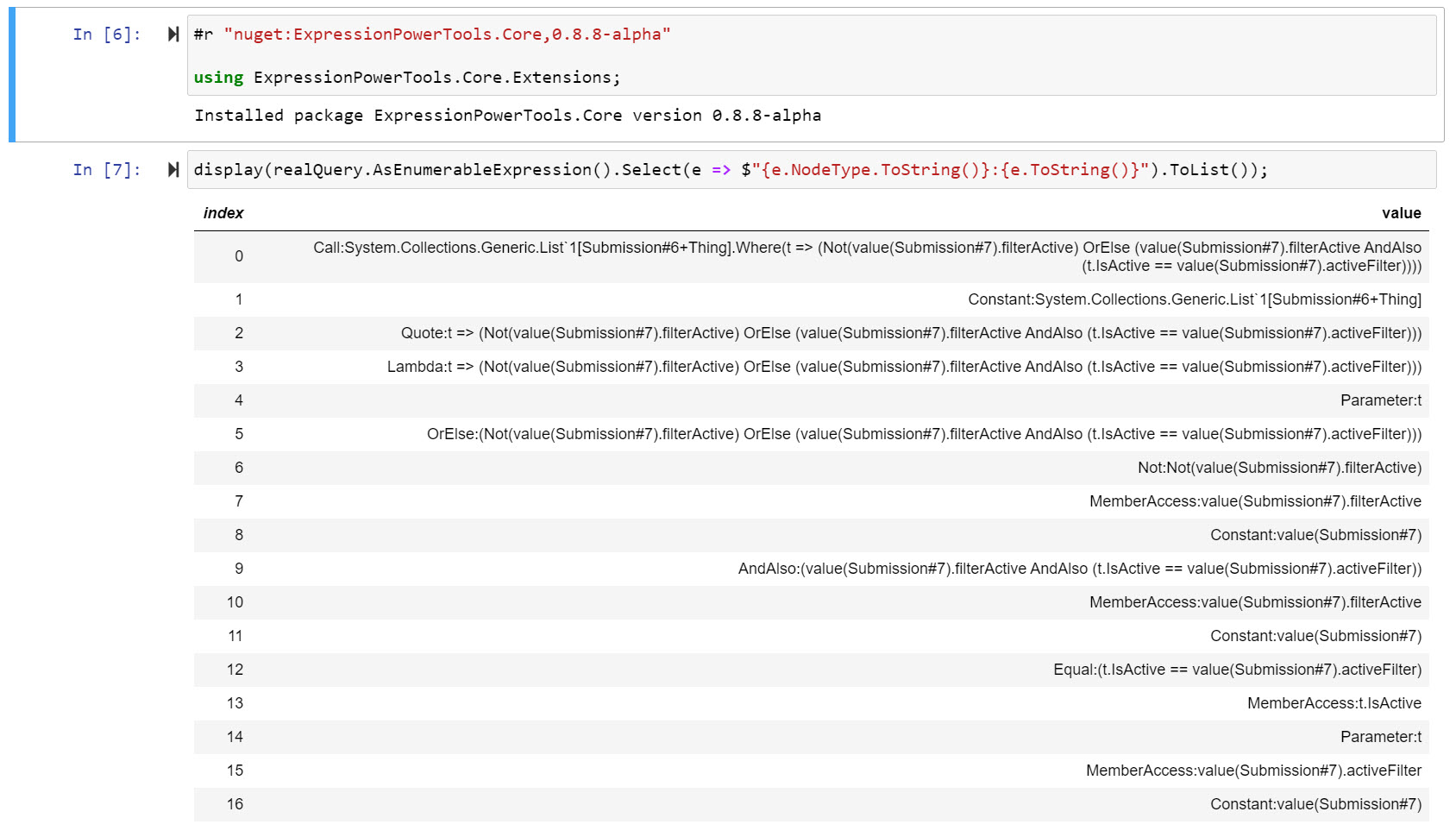

Let’s unroll the query. Here it is in a Jupyter notebook. I’ll follow up with more on notebooks in another post.

I installed the power tools and unrolled the query. Notice the MemberAccess nodes.

The variables filterActive and activeFilter are defined in my scope. If I serialize the query and send it to the server, there is no way to reference the variables! Instead, I have to transform the expression tree to pull out what I can.

Compression and Partial Compilation

To prepare the query for serialization, I first compile it to compress types. Local variables can be resolved to constants, but parameterized expressions must remain (these are ones that will be passed query entities or sent to the database for evaluation). Basically, when you see t => t.Id == myVariable the t.Id must be resolved later, whereas myVariable can be resolved now. The process takes multiple passes. First, a nominator recursively iterates expressions to find what candidates exist.

public override Expression Visit(Expression expression)

{

if (expression != null)

{

bool saveCannotBeEvaluated = cannotBeEvaluated;

cannotBeEvaluated = false;

base.Visit(expression);

if (!cannotBeEvaluated)

{

if (expression.NodeType != ExpressionType.Parameter)

{

if (expression.Type.Namespace != null

&& expression.Type.Namespace

.StartsWith($"{nameof(System)}.{nameof(System.Linq)}"))

{

cannotBeEvaluated = true;

}

else

{

candidates.Add(expression);

}

}

else

{

cannotBeEvaluated = true;

}

}

cannotBeEvaluated |= saveCannotBeEvaluated;

}

return expression;

}

The code is looking at a branch on the tree. If the branch has a parameter, it is not a candidate. If it doesn’t have parameters, it can be collapsed. Consider this:

BinaryExpression Equals

Left: Member Access t => t.Id (parameter)

Right: Member Access myVariable

The BinaryExpression has parameters so it is not a candidate. The left uses those parameters, so it is not a candidate. The right doesn’t take parameters as it simply accesses the variable directly, so it is tagged as a candidate. I also disqualify LINQ methods because those may try to evaluate expressions too soon (like Sum or Count). The candidates are then resolved:

LambdaExpression lambda = Expression.Lambda(e);

Delegate fn = lambda.Compile();

return Expression.Constant(fn.DynamicInvoke(null), e.Type);

This turns the variable into a constant with the variable value. The final passes simplify nodes. I’m still expanding on this, but consider the following:

BinaryExpression AND

Left BinaryExpression Equals

Left myVariable

Right myOtherVariable

Right BinaryExpression Equals

Left Member Access t => t.IsActive

Right Member Access myVariable

Let’s assume myVariable is false and myOtherVariable is true. In the evaluation pass it will transform it to look like this:

BinaryExpression AND

Left BinaryExpression Equals

Left false

Right true

Right BinaryExpression Equals

Left Member Access t => t.IsActive

Right Constant false

We won’t crunch the right side due to parameters. BUT we can certainly collapse the “equals” node:

BinaryExpression AND

Left false

Right BinaryExpression Equals

Left Member Access t => t.IsActive

Right Member Access myVariable

According to the rules for logical AND operations, if one side is false, the entire expression is false. Therefore, I can turn this node into:

Constant false

Here’s the code that parses an AND expression:

private Expression CompressAnd(BinaryExpression node)

{

if (TryCheckBoolean(node.Left, out bool left))

{

if (!left)

{

treeModified = true;

return Expression.Constant(false);

}

if (TryCheckBoolean(node.Right, out bool innerRight))

{

treeModified = true;

return Expression.Constant(innerRight);

}

treeModified = true;

return Visit(node.Right);

}

if (TryCheckBoolean(node.Right, out bool right))

{

if (!right)

{

treeModified = true;

return Expression.Constant(false);

}

treeModified = true;

return Visit(node.Left);

}

return base.VisitBinary(node);

}

private bool TryCheckBoolean(Expression expression, out bool value)

{

if (expression is ConstantExpression ce

&& ce.Type == typeof(bool))

{

value = (bool)ce.Value;

return true;

}

value = false;

return false;

}

Because the expression is now a constant, it is possible its parent can be simplified, too. The algorithm iterates multiple times until no expressions are modified. That closes the loop. After implementing the compression I could successfully serialize a query and deserialize it. Time to move the code into the Blazor scenario!

ASP.NET Middleware

I chose to go with ASP.NET Middleware and allow you to set up a route. To support multiple contexts, the endpoint includes the type of the DbContext and the name of the collection. A set of handlers parse the route information and map to the appropriate type and set. Assume you have a context named ThingsContext with a DbSet<Thing> named Things. The default routing will POST the serialized query to /efcore/ThingsContext/Things. We can use reflection to get the property for the collection:

if (typeof(DbContext).IsAssignableFrom(context))

{

var match = collection.ToLowerInvariant().Trim();

dbSet = context.GetProperties().FirstOrDefault(

p => p.Name.ToLowerInvariant() == match

&& p.PropertyType.IsGenericType

&& typeof(DbSet<>).IsAssignableFrom(p.PropertyType.GetGenericTypeDefinition()));

return dbSet != null;

}

Then we can build the AsQueryable extension to get an IQueryable. Here collection is the PropertyInfo of the collection we obtained in the previous code.

var dbSet = collection.GetValue(context);

var asQueryable = dbSet.GetType().GetMethod(nameof(Queryable.AsQueryable));

return asQueryable.Invoke(dbSet, null) as IQueryable;

Next, we can take the serialized query and build it on top of the IQueryable we just generated.

var request = await JsonSerializer.DeserializeAsync<SerializationPayload>(json);

var query = Serializer.DeserializeQuery(template, request.Json);

Finally, we execute the query by applying a method like ToArray and serialize the results:

private readonly MethodInfo toArray = typeof(Enumerable).GetMethods()

.First(m => m.Name == nameof(Enumerable.ToArray)

&& m.IsGenericMethodDefinition

&& m.GetParameters().Length == 1);

var typeList = new[] { query.ElementType };

var parameters = new object[] { query };

var arrayMethod = toArray.MakeGenericMethod(typeList);

result = arrayMethod.Invoke(null, parameters);

var json = JsonSerializer.Serialize(result);

var bytes = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(json);

return response.WriteAsync(bytes, 0, bytes.Length);

Running the sample app, we can see the serialized query going out and the serialized result coming in.

A Client Approach

The last step is to tie things together on the client. I wanted to allow you to shape your queries based on the existing DbContext, so I built a DbClientContext<T> where T: DbContext. The entry into a query is a lambda expression that references the DbSet like this:

var myQuery = DbClientContext<ThingsContext>(t => t.Things).Where(t => t.Id...)

The query uses a custom query host and provider that work like any other IQueryable but capture the context and collection. Instead of risking collision with existing extension methods, I decided to use ExecuteRemote to cast to the IRemoteQueryable<T> interface and cast the extensions from that. For example, here is the code for a query that returns a list:

public static Task<IList<T>> ToListAsync<T>(this IRemoteQueryable<T> query)

{

Ensure.NotNull(() => query);

return resolver.Value.ToListAsync(query as RemoteQuery<T, RemoteQueryProvider<T>>);

}

The resolver is an interface that is implemented using HttpClient but could be extended to use another protocol like gRPC-Web. The main work is done in this method:

if (!(query is IRemoteQuery remoteQuery))

{

throw new ArgumentException(

$"{query.GetType()} => {typeof(IRemoteQuery)}",

nameof(query));

}

var compressedQuery =

query.Provider.CreateQuery<T>(compressor.EvalAndCompress(query.Expression));

var json = Serializer.Serialize(compressedQuery);

var payload = new SerializationPayload(type)

{

Json = json,

};

var options = GetJsonSerializerOptions();

var transportPayload = JsonSerializer.Serialize(payload, options);

var requestContent = new StringContent(transportPayload);

var path = PathTransformer(remoteQuery);

var client = GetHttpClient();

var contentJson = await client.FetchRemoteQueryAsync(path, requestContent);

The query is compiled, serialized, and sent over the wire and response is fetched from the middleware.

Summary

I have learned quite a lot on the journey to build a seamless client for EF Core. The journey still continues, and I’ll post my findings as the project evolves. A mentor once told me, “It takes a lot of technology to create the illusion of simplicity.” Although that’s true, it’s also true that sometimes a simple, iterative approach is best way to tackle complex problems. Start at the desire result and work backwards. I hope that sharing this journey gives you knowledge and insights and that you continue to learn more about and appreciate the power of expressions.

Explore the Expression Power Tools on GitHub

Regards,

Related articles: