Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) Explained

Data-binding still delights after a decade

The purpose of this post is to provide an introduction to the Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) pattern. While I’ve participated in lots of discussions online about MVVM, it occurred to me that beginners who are learning the pattern have very little to go on and a lot of conflicting resources to wade through in order to try to implement it in their own code. I am not trying to introduce dogma but wanted to pull together key concepts in a single post to make it easy and straightforward to understand the value of the pattern and how it can be implemented. MVVM is really far simpler than people make it out to be.

This post was originally written in 2010 with Silverlight examples. The current article has been updated to use modern examples. If you’re interested, you can read the original at CodeProject.

For a more recent look at the patterns behind MVVM, read:

Learn the history of and decompose modern JavaScript frameworks like Angular, React, and Vue by learning about dependency injection, declarative syntax, and data-binding.

Why Care About MVVM

Why should you, as a developer, even care about the Model-View-ViewModel pattern? There are a number of benefits this pattern brought to WPF and Silverlight development, and are now reflected in modern front-end JavaScript frameworks (often called _MV*_ when they don’t explicitly provide a viewmodel). Before you go on, ask yourself:

- Do you need to share a project with a designer, and have the flexibility for design work and development work to happen near-simultaneously?

- Do you require thorough unit testing for your solutions?

- Is it important for you to have reusable components, both within and across projects in your organization?

- Would you like more flexibility to change your user interface without having to refactor other logic in the code base?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, these are just a few of the benefits that using the MVVM model can bring for your project.

I’ve been amazed at some conversations I’ve read online. Things like, “MVVM only makes sense for extremely complex UI” or “MVVM always adds a lot of overhead and is too much for smaller applications.” The real kicker was, “MVVM doesn’t scale.” In my opinion, statements like this speak to knowledge and implementation of MVVM, not MVVM itself. In other words, if you think it takes hours to wire up MVVM, you’re not doing it right. If your application isn’t scaling, don’t blame MVVM, blame how you are using MVVM. Binding 100,000 items to a list box can be just silly regardless of what pattern you are following.

So the quick disclaimer: this is MVVM as I know it, not MVVM as a universal truth. I encourage you to share your thoughts, experiences, feedback, and opinions using the comments. If you feel something is incorrect, let me know and I’ll do my best to keep this post updated and current.

MVVM at a Glance

Let’s examine the pieces of the MVVM pie. We’ll start with the basic building block that is key for all applications: data and information. This is held in the model.

The Model

The model is what I like to refer to as the domain object. The model represents the actual data and/or information we are dealing with. An example of a model might be a contact (containing name, phone number, address, etc.) or the characteristics of a live streaming publishing point.

The key to remember with the model is that it holds the information, but not behaviors or services that manipulate the information. It is not responsible for formatting text to look pretty on the screen, or fetching a list of items from a remote server (in fact, in that list, each item would most likely be a model of its own). Business logic is typically kept separate from the model, and encapsulated in other classes that act on the model. This is not always true: for example, some models may contain validation.

It is often a challenge to keep a model completely “clean.” By this I mean a true representation of “the real world.” For example, a contact record may contain a last modified date and the identity of the modifying user (auditing information), and a unique identifier (database or persistence information). The modified date has no real meaning for a contact in the real world but is a function of how the model is used, tracked, and persisted in the system.

This is a simple example of a model expressed as a JSON (JavaScript) object. The model contains a list of items and associated prices.

[

{ id: 1, name: "Computer", price: 199.99 },

{ id: 2, name: "Car", price: 39999.99 },

{ id: 3, name: "House", price: 199999.99 }

]The View

The view is what most of us are familiar with and the only thing the end user really interacts with. It is the presentation of the data. The view takes certain liberties to make this data more presentable. For example, a date might be stored on the model as number of seconds since midnight on January 1, 1970 (Unix Time). To the end user, however, it is presented with the month name, date, and year in their local time zone. A view can also have behaviors associated with it, such as accepting user input. The view manages input (key presses, mouse movements, touch gestures, etc.) which ultimately manipulates properties of the model.

In MVVM, the view is active. As opposed to a passive view which has no knowledge of the model and is completely manipulated by a controller/presenter, the view in MVVM contains behaviors, events, and data-bindings that ultimately require knowledge of the underlying model and viewmodel. While these events and behaviors might be mapped to properties, method calls, and commands, the view is still responsible for handling it’s own events and does not turn this completely over to the viewmodel.

One thing to remember about the view is that it is not responsible for maintaining its state. Instead, it will synchronize this with the viewmodel.

Here is how to define a view using the legacy Angular.js framework.

<div ng-app='myApp' class="container">

<div class="row">

<div class="h2">{{selected.name}}</div>

<div class="h2">{{selected.price|currency}}</div>

<button class="btn btn-warning" ng-click="selected.price = selected.price * 2">Double</button>

</div>

<div class="row">

<hr/>

</div>

<div class="row">

<ul>

<li class="btn btn-success"

ng-class="{ 'btn-danger' : selected.id==item.id }"

ng-click="pick(item)"

ng-repeat="item in list">{{item.name}}</li>

</ul>

</div>

</div>Notice that it uses valid HTML that is extended with features like data-binding to properties ({{selected.name}}) and functions (ng-click). The model contains a list, but it’s the view that defines how that list is rendered using the ng-repeat directive. The model contains a number in selected.price but it is passed through a currency filter to display as money.

The ViewModel (Our Controller/Presenter)

The viewmodel is a key piece of the triad because it introduces Presentation Separation, or the concept of keeping the nuances of the view separate from the model. Instead of making the model aware of the user’s view of a date, so that it converts the date to the display format, the model simply holds the data, the view simply holds the formatted date, and the controller acts as the liaison between the two. The controller might take input from the view and place it on the model, or it might interact with a service to retrieve the model, then translate properties and place it on the view.

The viewmodel also exposes methods, commands, and other points that help maintain the state of the view, manipulate the model as the result of actions on the view, and trigger events in the view itself.

MVVM, while it evolved “behind the scenes” for quite some time, was introduced to the public in 2005 via Microsoft’s John Gossman blog post about Avalon (the code name for Windows Presentation Foundation, or WPF). The blog post is entitled, Introduction to Model/View/ViewModel pattern for building WPF Apps and generated quite a stir judging from the comments as people wrapped their brains around it.

I’ve heard MVVM described as an implementation of Presentation Model designed specifically for WPF (and later, Silverlight).

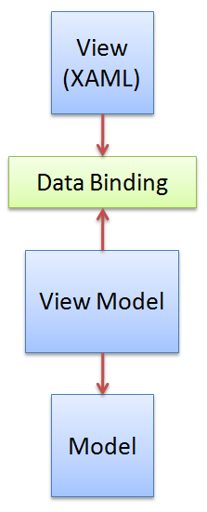

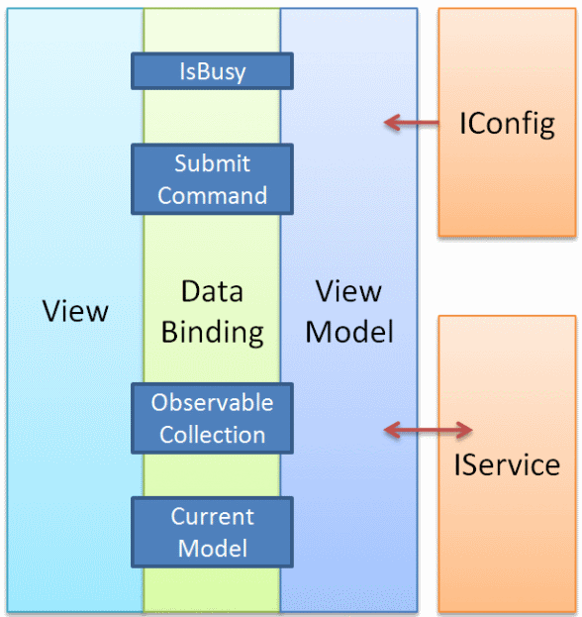

The examples of the pattern often focus on XAML for the view definition and data-binding for commands and properties. These are more implementation details of the pattern rather than intrinsic to the pattern itself, which is why I offset data-binding with a different color:

Here is what a sample viewmodel looks like, expanding our Angular.js example.

(function (app) {

app.value('list', [{ id: 1, name: "Computer", price: 199.99 },

{id: 2, name: "Car", price: 39999.99 },

{id: 3, name: "House", price: 199999.99 }]);

app.run(['$rootScope', 'list', function (rs, l) {

rs.list = l;

rs.selected = l[0];

rs.pick = function (item) {

rs.selected = item;

};

}]);

})(angular.module('myApp', []));The viewmodel exposes the model as a value named list and sets the list to a scope that then participates in real-time data-binding. The pick method is used to select an item from the list for display in the view that was defined earlier.

For larger applications, I prefer to wire in references externally or use a dependency injection framework. Learn more about dependency injection here:

Large JavaScript projects may have dozens or even hundreds of related components interacting with each other. Managing dependencies between components can become incredibly complex if you aren't taking advantage of dependency injection. Learn what DI is and how to implement it with a simple reference application.

What’s nice is we have the flexibility to build it like this initially and then refactor as needed - again, you do not have to use any of these frameworks to take advantage of the pattern, as you can see from this example. It fetches the list right away, which is a hard-coded list of values.

Putting it Together

Let’s get a little more specific and look at how this would be implemented in a sample application. Here is what an X-ray of a sample MVVM set up may look like:

So what can we gather from this snapshot?

First, the IConfig represents a configuration service (in a newsreader it may contain the account information and feeds that are being fetched), while the IService is “some service” - perhaps the interface to fetch feeds from RSS sources in a news reader application.

The View and the ViewModel

- The view and the viewmodel communicate via data-binding, method calls, properties, events, and messages

- The viewmodel exposes not only models, but other properties (such as state information, like the “is busy” indicator) and commands (functions that are called to handle events)

- The view handles its own UI events, then maps them to the viewmodel via commands

- The models and properties on the viewmodel are updated from the view via two-way data-binding

The ViewModel and the Model

The viewmodel becomes wholly responsible for the model in this scenario. Fortunately, it’s not alone:

- The viewmodel may expose the model directly, or properties related to the model, for data-binding

- The viewmodel can contain interfaces to services, configuration data, etc. in order to fetch and manipulate the properties it exposes to the view

The Chicken or the Egg

You might have heard discussion about view first or viewmodel first. In general, I believe most developers agree that a view should have exactly one viewmodel. There is no need to attach multiple viewmodels to a single view. If you think about separation of concerns, this makes sense, because if you have a “contact widget” on the screen bound to a “contact viewmodel” and a “company widget” bound to a “company viewmodel”, these should be separate views, not a single view with two viewmodels.

A view may be composed of other views, each with its own viewmodel. Viewmodels might compose other viewmodels when necessary (often, however, I see people composing and aggregating viewmodels when in fact what they really want is messaging between viewmodels).

While a view should only have one viewmodel, a single viewmodel might be used by multiple views (imagine a wizard, for example, that has three views but all bind to the same viewmodel that drives the process).

Complete Examples

This is the complete example using Angular.js:

To compare, here is a different example using Vue.js:

And finally, an example using plain Vanilla.js:

What MVVM Isn’t

No discussion would be complete unless we talked about what MVVM isn’t.

MVVM isn’t a complete framework. It’s a pattern, and might be part of a framework, but it’s only a piece of the overall solution for your application architecture. It doesn’t address, and doesn’t really care, about what happens on your server or how your services are put together. It does stress separation of concerns, which is nice.

I bet that nowhere in this article did you read a rule that stated, “With MVVM, code-behind is not allowed”. This is a raging debate, but the pattern itself doesn’t tell you how to implement your view, whether that is with XAML, HTML, code-behind, JavaScript, or a combination of everything. I would suggest that if you are spending days writing something just to avoid minutes of code-behind, your approach is wrong.

It is not required for all applications. I believe that line-of-business, data-driven, and forms-based applications are prime candidates for MVVM. Games, entertainment websites, paint programs, and others may not make sense. Be sure you are using the right tool for the right job.

MVVM is not supposed to slow you down! All new patterns and frameworks come with a learning curve. You’ll have to accept that your developers need to learn and understand the pattern, but you should not accept that your entire process suddenly takes longer or becomes delayed. The pattern is useful when it accelerates development, improves stability and performance, reduces risk, and so forth. When it slows development, introduces problems, and has your developers cringing whenever they hear the phrase “design pattern”, you might want to rethink your approach.

Conclusion

Hopefully this helps illustrate what MVVM, why it is useful, and helps you better understand modern frameworks that are based on the _MV*_ paradigm.

Appendix: Before MVVM

MVVM is fairly recent in the longer history of design or view patterns. Here are a few older and popular patterns with illustrations.

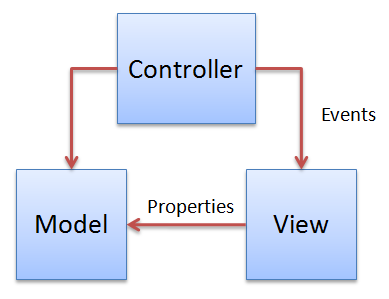

Model-View-Controller (MVC)

This software architecture pattern was first described in the context of Smalltalk at Xerox in 1979. If you are interested, you can download some of those original papers (PDF format) by clicking here (PDF).

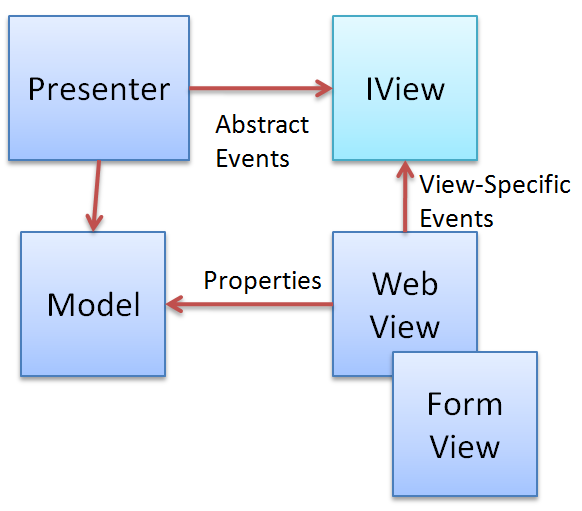

Model-View-Presenter (MVP)

In 1996, the Model-View-Presenter pattern (PDF) was introduced to the world. This pattern builds on MVC but places special constraints on the controller, now called the presenter. A general overview looks like this:

Martin Fowler describes this pattern with two flavors: the Supervising Controller/Presenter and the Passive View.

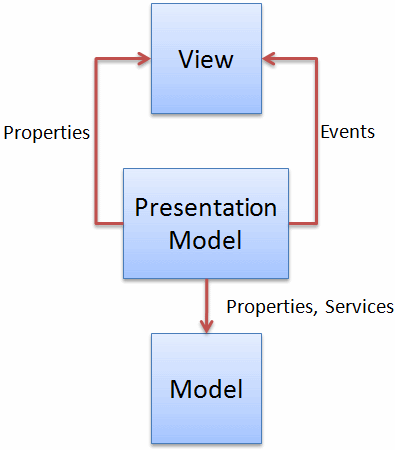

Presentation Model

In 2004, Martin Fowler published his description of the Presentation Model. The summary is quite succinct: “Represent the state and behavior of the presentation independently of the GUI controls used in the interface.” As you can see, MVVM is a specialized form of this pattern:

Thanks for reading! Please share your thoughts and feedback below.

Regards,