Azure Cosmos DB With EF Core on Blazor Server

A planetary example for planetary scale

Like many other .NET developers, I was very skeptical of a NoSQL “ORM” when I joined the EF Core team in early 2020. After all, doesn’t the “R” stand for “relational?”

🤣 Dad (or Bad) joke: What’s a pirate’s favorite letter? Everyone: “RRRrrrrrrrr.” Me: “No, it B the C we love!”

I quickly learned to appreciate the potential when I began to dive into the details. I’m not trying to sell you on the idea, but do want to share what I’ve learned.

- It’s used in production for large volume and high velocity workloads. A team at Microsoft, for example, uses it to ingest data and “fan out” to a SQL Server and a Cosmos DB instance.

- Developers appreciate the easy of setup… until they don’t. There is a great getting started story but we still have work to do to grow up, specifically when it comes to changing assumptions and conventions. More on that later.

- The most requested provider for EF Core (that doesn’t already exist) is MongoDB. That shows there is an appetite to use the EF Core APIs for document databases.

I’ve had requests to show what a “full” app featuring updates and queries look like for some time. The recent Azure Cosmos DB Conference gave me the opportunity to build one. I introduced the reference app and explained it at a high level here (this post gets into far more detail than I could in my session):

Azure Cosmos DB with Entity Framework Core

I’m happy to share with you the “Planetary Docs” demo. It includes:

- EF Core-isms

- An Azure Cosmos DB

DbContext - Entity relationships configuration

- Container and discriminator configuration

- An Azure Cosmos DB

- Azure Cosmos DB-isms

- Partition key management

- Handling “related entities”

- Blazor-isms

- Keyboard input

- Bookmarking query pages

- Transforming Markdown to HTML

- Rendering HTML with a cool “cheat”

- Handling large fields in Blazor Server with another “cheat”

It is available on GitHub:

This blog post walks through all you need to know about the project!

Quickstart

The best way to get started is to follow the Planetary Docs quickstart. The steps involve:

- Clone the repo

- Set up Azure Cosmos DB and/or use the emulator

- Clone the ASP.NET Core docs repo

- Install and seed the database using a console app

- Run and start using the Blazor Server app

I understand if you’re impatient and are already pulling down code to get up and running. If you don’t mind, however, I’d like to provide a gentle introduction to the concept behind the app.

Introducing Planetary Docs

You may (or may not) know that Microsoft’s official documentation runs entirely on open source. It uses markdown with some metadata enhancements to build the interactive documentation that .NET developers use daily. The hypothetical scenario for Planetary Docs is to provide a web-based tool for authoring the docs. It allows setting up the title, description, the alias of the author, assigning tags, editing markdown and previewing the HTML output.

It’s planetary because Azure Cosmos DB is “planetary scale.” I also recently took up a new hobby: deep sky astrophotography. This was a great opportunity for me to arbitrarily toss in a stylized photo of M42 (the Great Orion Nebula). I flexed some of my Blazor skills as well.

The app provides the ability to search documents. Documents are stored under aliases and tags for fast lookup, but full text search is available as well. The app automatically audits the documents (it takes snapshots of the document anytime it is edited and provides a view of the history). As of writing this, delete and restore aren’t implemented yet. I filed issue #3 to add delete capability and issue #4 to provide restore capability for anyone interested.

Here’s a look at the document for Document:

public class Document

{

public string Uid { get; set; }

public string Title { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public DateTime PublishDate { get; set; }

public string Markdown { get; set; }

public string Html { get; set; }

public string AuthorAlias { get; set; }

public List<string> Tags { get; set; }

= new List<string>();

public string ETag { get; set; }

public override int GetHashCode() => Uid.GetHashCode();

public override bool Equals(object obj) =>

obj is Document document && document.Uid == Uid;

public override string ToString() =>

$"Document {Uid} by {AuthorAlias} with {Tags.Count} tags: {Title}.";

}

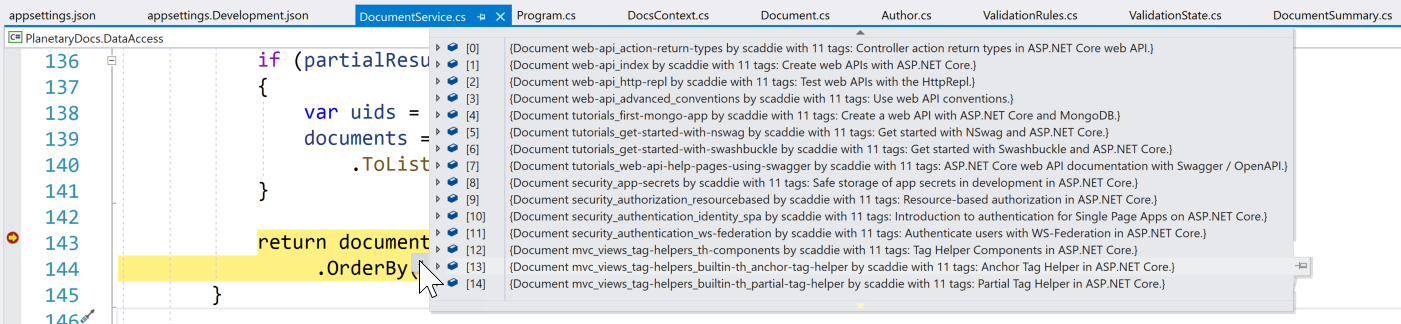

💡 Coding tip: I always implement a meaningful hash code and override

Equalsto behave the way that makes sense for my domain objects. That way, list lookups and useful containers likeHashSet“just work.” I also like to have a goodToString()override so my debug view gives me good “at a glance” information.

Here’s what viewing a list of documents during a debug session looks like in Visual Studio:

For faster lookups, I created a DocumentSummary class that contains some basic information about the document.

public class DocumentSummary

{

public DocumentSummary()

{

}

public DocumentSummary(Document doc)

{

Uid = doc.Uid;

Title = doc.Title;

AuthorAlias = doc.AuthorAlias;

}

public string Uid { get; set; }

public string Title { get; set; }

public string AuthorAlias { get; set; }

public override int GetHashCode() => Uid.GetHashCode();

public override bool Equals(object obj) =>

obj is DocumentSummary ds && ds.Uid == Uid;

public override string ToString() =>

$"Summary for {Uid} by {AuthorAlias}: {Title}.";

}

This is used by both Author and Tag. They look pretty similar. Here’s the Tag code:

public class Tag : IDocSummaries

{

public string TagName { get; set; }

public List<DocumentSummary> Documents { get; set; }

= new List<DocumentSummary>();

public string ETag { get; set; }

public override int GetHashCode() => TagName.GetHashCode();

public override bool Equals(object obj) =>

obj is Tag tag && tag.TagName == TagName;

public override string ToString() =>

$"Tag {TagName} tagged by {Documents.Count} documents.";

}

Immediately you ask, “Jeremy, what’s the ETag all about?”

Thanks for asking! To keep things simple, I implement the property on the model so it follows the model around. This is used for concurrency in Azure Cosmos DB. I implemented concurrency support in the sample app (try opening the same document in two tabs, then updating one and saving it, and finally updating the other and saving it.)

Because people often struggle with disconnected entities in EF Core, I chose to use that pattern in this app. It’s not necessary in Blazor Server but makes it easier to scale the app. The alternative approach is to track the state of the entity with EF Core’s incredible change tracker. The change tracker would enable me to drop the ETag property and use a shadow property instead.

Finally, there is the DocumentAudit document.

public class DocumentAudit

{

public DocumentAudit()

{

}

public DocumentAudit(Document document)

{

Id = Guid.NewGuid();

Uid = document.Uid;

Document = JsonSerializer.Serialize(document);

Timestamp = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow;

}

public Guid Id { get; set; }

public string Uid { get; set; }

public DateTimeOffset Timestamp { get; set; }

public string Document { get; set; }

public Document GetDocumentSnapshot() =>

JsonSerializer.Deserialize<Document>(Document);

}

Ideally, the Document snapshot would be a proper property (yeah, I went there) instead of a string. This is one of the EF Core Azure Cosmos DB provider limitations EF Core currently has. There is not currently a way for Document to do double-duty as both a standalone entity and an “owned” entity. If I want the user to be able to search on properties in the historical document, I could either add those properties to the DocumentAudit class to be automatically indexed, or make a DocumentSnapshot class that shares the same properties but is configured as “owned” by the DocumentAudit parent.

My domain is ready. Let’s create the strategy to store these documents in a document database.

Azure Cosmos DB setup

My strategy for the data store is to use three containers.

One container named Documents is dedicated exclusively to documents. They are partitioned by id. Yes, there is one partition per document. Why on earth would I do that? Here’s the answer.

The audits are contained in a container (wow, we really got the naming right on that one) named, well, Audits. The partition key is the document id, so all histories are stored in the same partition. Seems to me to be a reasonable strategy since I’ll only ever ask for history for a single document.

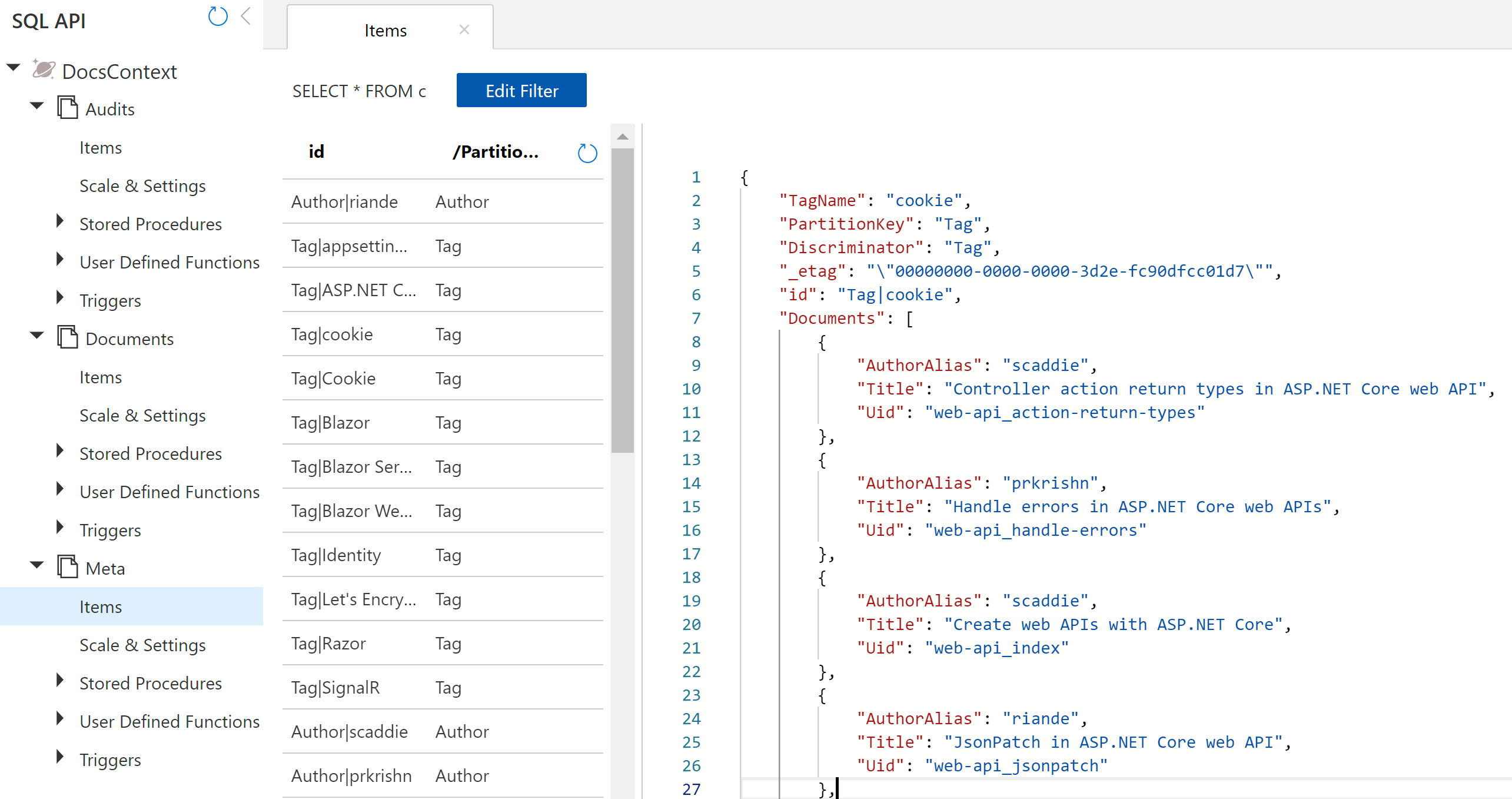

Finally, there is some metadata that is stored in Meta (I know, it’s so meta). The partition key is the meta data type, either Author or Tag. The metadata contains summaries of the related documents. If I want to search for documents with tag x I don’t have to scan all documents. Instead, I read the document for tag x and it contains a collection of the related documents it is tagged in. This obviously means keeping the summaries up to date. More on that in a bit.

Here’s a peek at a tag for “cookie”.

Although this is the plan for the database, I actually don’t lift a finger in the portal to create anything. Instead, I configured a model in EF Core and set up the application to generate documents based on that model.

Entity Framework Core

It all starts with the DbContext. This is how your application informs EF Core of what is important to track and how your domain model is mapped to the underlying data store. The DbContext for Planetary Docs is named DocsContext in the PlanetaryDocs.DataAccess project. For the context, I use my favorite anti-magic string “trick” to define the name of the partition key field and the name of the container that will hold metadata.

public const string PartitionKey = nameof(PartitionKey);

private const string Meta = nameof(Meta);

I define a constructor that takes a DbContextOptions<DocsContext> parameter and passes it to the base class to enable run-time configuration.

public DocsContext(DbContextOptions<DocsContext> options)

: base(options) =>

SavingChanges += DocsContext_SavingChanges;

What’s that? Did I just hook into an event? I did! More on that in a minute. Next, I use the DbSet<> generic type to specify the classes that should be persisted.

public DbSet<DocumentAudit> Audits { get; set; }

public DbSet<Document> Documents { get; set; }

public DbSet<Tag> Tags { get; set; }

public DbSet<Author> Authors { get; set; }

I placed a few helper methods on the DbContext to make it easier to search for and assign metadata. Both metadata items use a string-based key and specify the type as the partition key. This enables a generic strategy to find records:

public async ValueTask<T> FindMetaAsync<T>(string key)

where T : class, IDocSummaries

{

var partitionKey = ComputePartitionKey<T>();

try

{

return await FindAsync<T>(key, partitionKey);

}

catch (CosmosException ce)

{

if (ce.StatusCode == HttpStatusCode.NotFound)

{

return null;

}

throw;

}

}

The nice thing about FindAsync (the existing method on the base DbContext that is shipped as part of EF Core) is that it doesn’t require closing the type to specify the key. It takes it as an object parameter and applies it based on the internal representation of the model.

“Jeremy, where is this model of which you speak?'

We’ll get there in a second. Wait for it… OK.

In the OnModelCreating overload, we configure the entities and fluently assert how they should persist. Here’s the first configuration for DocumentAudit.

modelBuilder.Entity<DocumentAudit>()

.HasNoDiscriminator()

.ToContainer(nameof(Audits))

.HasPartitionKey(da => da.Uid)

.HasKey(da => new { da.Id, da.Uid });

This configuration informs EF Core that…

- There will only be one type stored in the table, so there is no need for a discriminator to distinguish types.

- The documents should be stored in a container named

Audits. - The partition key is the document id.

- The access key is the unique identifier of the audit combined with the partition key (the unique identifier of the document).

Next, we configure the Document:

var docModel = modelBuilder.Entity<Document>();

docModel.ToContainer(nameof(Documents))

.HasNoDiscriminator()

.HasKey(d => d.Uid);

docModel.HasPartitionKey(d => d.Uid)

.Property(p => p.ETag)

.IsETagConcurrency();

docModel.Property(d => d.Tags)

.HasConversion(

t => ToJson(t),

t => FromJson<List<string>>(t));

Here we specify a few more details.

- The

ETagproperty should be mapped as concurrency. - A conversion is used to serialize and deserialize the tags list. This is a workaround for the fact that EF Core doesn’t handle collections of primitive types.

The Tag and Author configuration is similar. Here is the definition for Tag:

var tagModel = modelBuilder.Entity<Tag>();

tagModel.Property<string>(PartitionKey);

tagModel.HasPartitionKey(PartitionKey);

tagModel.ToContainer(Meta)

.HasKey(nameof(Tag.TagName), PartitionKey);

tagModel.Property(t => t.ETag)

.IsETagConcurrency();

tagModel.OwnsMany(t => t.Documents);

A few notes:

- The partition key is configured as a shadow property. Unlike the

ETagproperty, the partition key is fixed and therefore doesn’t have to live on the model. - The

OwnsManyis used to inform EF Core thatDocumentSummarydoesn’t live in its own documents, but should always be included as part of the parentTagdocument.

The last point is important. In a relational database, you’d likely normalize the summaries in a table and define them with a relationship. This is an anti-pattern in document databases because the extra lookup adds significant overhead compared to including it in the document. This is an example of a DbContext that either can’t be shared between providers or would require some conditional logic. In document databases, ownership should be implied. If you agree, please like this issue to add your vote!

Read this to learn more about models in EF Core: Creating and configuring a model.

Don’t worry, I didn’t forget about the SaveChanges event. I use that to automatically insert a document snapshot any time a document is inserted or updated. Every time changes are saved and the event is fired, I tap into EF Core’s powerful ChangeTracker and ask it to give me any Document entities that were added or updated. I then insert an audit entry for each one.

private void DocsContext_SavingChanges(

object sender,

SavingChangesEventArgs e)

{

var entries = ChangeTracker.Entries<Document>()

.Where(

e => e.State == EntityState.Added ||

e.State == EntityState.Modified)

.Select(e => e.Entity)

.ToList();

foreach (var docEntry in entries)

{

Audits.Add(new DocumentAudit(docEntry));

}

}

Doing it this way will ensure audits are generated even if you build other apps that share the same DbContext.

The Data Service

I’m often asked if developers should use the repository pattern with EF Core, and my answer is always, “It depends.” To the extent that the DbContext is testable and can be interfaced for mocking, there are many cases when using it directly is perfectly fine. Whether or not you specifically use the repository pattern, adding a data access layer often makes sense when there are database-related tasks to do outside of the EF Core functionality. In this case, there is database-related logic that makes more sense to isolate rather than bloating the DbContext, so I implemented a DocumentService.

The service is constructed with a DbContext factory. This is provided by EF Core to easily create new contexts using your preferred configuration. The app uses a “context per operation” rather than using long-lived contexts and change tracking. Here’s the configuration to grab the settings and tell the factory to make contexts that connect to Azure Cosmos DB. The factory is then automatically injected into the service.

services.Configure<CosmosSettings>(

Configuration.GetSection(nameof(CosmosSettings)));

services.AddDbContextFactory<DocsContext>(

(IServiceProvider sp, DbContextOptionsBuilder opts) =>

{

var cosmosSettings = sp

.GetRequiredService<IOptions<CosmosSettings>>()

.Value;

opts.UseCosmos(

cosmosSettings.EndPoint,

cosmosSettings.AccessKey,

nameof(DocsContext));

});

services.AddScoped<IDocumentService, DocumentService>();

Using this pattern allowed me to demonstrate disconnected entities and also builds some resiliency against the case when your Blazor SignalR circuit may break.

Load a document

The document load is intended to get a snapshot that isn’t tracked for changes because those will be sent in a separate operation. The main requirement is to set the partition key.

private static async Task<Document> LoadDocNoTrackingAsync(

DocsContext context, Document document) =>

await context.Documents

.WithPartitionKey(document.Uid)

.AsNoTracking()

.SingleOrDefaultAsync(d => d.Uid == document.Uid);

Query documents

The document query allows the user to search on text anywhere in the document and to further filter by author and/or tag. The pseudo code looks like this:

- If there is a tag, load the tag and use the document summary list as the result set

- If there is also an author, load the author and filter the results to the intersection of results between tag and author

- If there is text, load the documents that match the text then filter the results to the author and tag intersection

- If there is also text, load the documents that match the text then filter the results to the tag results

- If there is also an author, load the author and filter the results to the intersection of results between tag and author

- Else if there is an author, load the author and filter the results to the document summary list as the result set

- If there is text, load the documents that match the text then filter the results to the author results

- Else load the documents that match the text

Performance-wise, a tag and/or author-based search only requires one or two documents to be loaded. A text search always loads matching documents and then further filters the list based on the existing documents, so it is significantly slower (but still fast).

Here’s the implementation. Note the HashSet just works because I overrode Equals and GetHashCode:

public async Task<List<DocumentSummary>> QueryDocumentsAsync(

string searchText,

string authorAlias,

string tag)

{

using var context = factory.CreateDbContext();

var result = new HashSet<DocumentSummary>();

bool partialResults = false;

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(authorAlias))

{

partialResults = true;

var author = await context.FindMetaAsync<Author>(authorAlias);

foreach (var ds in author.Documents)

{

result.Add(ds);

}

}

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(tag))

{

var tagEntity = await context.FindMetaAsync<Tag>(tag);

IEnumerable<DocumentSummary> resultSet =

Enumerable.Empty<DocumentSummary>();

if (partialResults)

{

resultSet = result.Intersect(tagEntity.Documents);

}

else

{

resultSet = tagEntity.Documents;

}

result.Clear();

foreach (var docSummary in resultSet)

{

result.Add(docSummary);

}

partialResults = true;

}

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(searchText))

{

return result.OrderBy(r => r.Title).ToList();

}

if (partialResults && result.Count < 1)

{

return result.ToList();

}

var documents = await context.Documents.Where(

d => d.Title.Contains(searchText) ||

d.Description.Contains(searchText) ||

d.Markdown.Contains(searchText))

.ToListAsync();

if (partialResults)

{

var uids = result.Select(ds => ds.Uid).ToList();

documents = documents.Where(d => uids.Contains(d.Uid))

.ToList();

}

return documents.Select(d => new DocumentSummary(d))

.OrderBy(ds => ds.Title).ToList();

}

Now we can query documents, but how do we make them?

Create a document

Ordinarily, creating a document with EF Core would be as easy as:

context.Add(document);

await context.SaveChangesAsync();

For PlanetaryDocs however, the document can have associated tags and an author. These have summaries that must be updated explicitly because there are no formal relationships.

📝 Note: This example uses code to keep documents in sync. If the database is used by multiple applications and services, it may make more sense to implement the logic at the database level and use triggers and stored procedures instead.

A generic method handles keeping the documents in sync. The pseudo code is the same whether it is for an author or a tag:

- If the document was inserted or updated

- A new document will result in “author changed” and “tags added”

- If the author was changed or a tag removed

- Load the metadata document for the old author or removed tag

- Remove the document from the summary list

- If the author was changed

- Load the metadata document for the new author

- Add the document to the summary list

- Load all tags for the model

- Update the author in the summary list for each tag

- If tags were added

- If tag exists

- Load the metadata document for the tag

- Add the document to the summary list

- Else

- Create a new tag with the document in the summary list

- If tag exists

- If the document was updated and the title changed

- Load the metadata for the existing author and/or tags

- Update the title in the summary list

This algorithm is an example of how EF Core shines. All of these manipulations can happen in a single pass. If a tag is referenced multiple times, it is only ever loaded once. The final call to save changes will commit all changes including inserts.

Here’s the code for handling changes to tags that is called as part of the insert process:

private static async Task HandleTagsAsync(

DocsContext context,

Document document,

bool authorChanged)

{

var refDoc = await LoadDocNoTrackingAsync(context, document);

var updatedTitle = refDoc != null && refDoc.Title != document.Title;

if (refDoc != null)

{

var removed = refDoc.Tags.Where(

t => !document.Tags.Any(dt => dt == t));

foreach (var removedTag in removed)

{

var tag = await context.FindMetaAsync<Tag>(removedTag);

if (tag != null)

{

var docSummary =

tag.Documents.FirstOrDefault(

d => d.Uid == document.Uid);

if (docSummary != null)

{

tag.Documents.Remove(docSummary);

context.Entry(tag).State = EntityState.Modified;

}

}

}

}

var tagsAdded = refDoc == null ?

document.Tags : document.Tags.Where(

t => !refDoc.Tags.Any(rt => rt == t));

if (updatedTitle || authorChanged)

{

var tagsToChange = document.Tags.Except(tagsAdded);

foreach (var tagName in tagsToChange)

{

var tag = await context.FindMetaAsync<Tag>(tagName);

var ds = tag.Documents.SingleOrDefault(ds => ds.Uid == document.Uid);

if (ds != null)

{

ds.Title = document.Title;

ds.AuthorAlias = document.AuthorAlias;

context.Entry(tag).State = EntityState.Modified;

}

}

}

foreach (var tagAdded in tagsAdded)

{

var tag = await context.FindMetaAsync<Tag>(tagAdded);

if (tag == null)

{

tag = new Tag { TagName = tagAdded };

context.SetPartitionKey(tag);

context.Add(tag);

}

else

{

context.Entry(tag).State = EntityState.Modified;

}

tag.Documents.Add(new DocumentSummary(document));

}

}

The algorithm as implemented works for inserts, updates, and deletes.

Update a document

Now that the metadata sync has been implemented, the update code is simple:

public async Task UpdateDocumentAsync(Document document)

{

using var context = factory.CreateDbContext();

await HandleMetaAsync(context, document);

context.Update(document);

await context.SaveChangesAsync();

}

Concurrency works in this scenario because we persist the loaded version of the entity in the ETag property.

Delete a document

The delete code uses a simplified algorithm to remove existing tag and author references.

public async Task DeleteDocumentAsync(string uid)

{

using var context = factory.CreateDbContext();

var docToDelete = await LoadDocumentAsync(uid);

var author = await context.FindMetaAsync<Author>(docToDelete.AuthorAlias);

var summary = author.Documents.Where(d => d.Uid == uid).FirstOrDefault();

if (summary != null)

{

author.Documents.Remove(summary);

context.Update(author);

}

foreach (var tag in docToDelete.Tags)

{

var tagEntity = await context.FindMetaAsync<Tag>(tag);

var tagSummary = tagEntity.Documents.Where(d => d.Uid == uid).FirstOrDefault();

if (tagSummary != null)

{

tagEntity.Documents.Remove(tagSummary);

context.Update(tagEntity);

}

}

context.Remove(docToDelete);

await context.SaveChangesAsync();

}

Search metadata (tags or authors)

Finding tags or authors that match a text string is a straightforward query. The key is to improve performance and reduce the cost (literally, as in dollars) of the query by making it a single partition query.

public async Task<List<string>> SearchAuthorsAsync(string searchText)

{

using var context = factory.CreateDbContext();

var partitionKey = DocsContext.ComputePartitionKey<Author>();

return (await context.Authors

.WithPartitionKey(partitionKey)

.Select(a => a.Alias)

.ToListAsync())

.Where(

a => a.Contains(searchText, System.StringComparison.InvariantCultureIgnoreCase))

.OrderBy(a => a)

.ToList();

}

The ComputePartitionKey method returns the simple type name as the partition. The authors list is not long so I pull down the aliases first, then apply an in-memory filter for the contains logic.

Deal with document audits

The last set of APIs deal with the automatically generated audits. This method loads document audits then projects them onto a summary. I don’t do the projection in the query because it requires deserializing the snapshot. Instead, I get the list of audits, then deserialize the snapshots and pull out the relevant data to display such as title and author.

public async Task<List<DocumentAuditSummary>> LoadDocumentHistoryAsync

(string uid)

{

using var context = factory.CreateDbContext();

return (await context.Audits

.WithPartitionKey(uid)

.Where(da => da.Uid == uid)

.ToListAsync())

.Select(da => new DocumentAuditSummary(da))

.OrderBy(das => das.Timestamp)

.ToList();

}

The ToListAsync materializes the query results and everything after is manipulated in memory.

The app also lets you review an audit record using the same viewer control that live documents use. A method loads the audit, materializes the snapshot and returns a Document entity for the view to use.

public async Task<Document> LoadDocumentSnapshotAsync(

System.Guid guid,

string uid)

{

using var context = factory.CreateDbContext();

try

{

var audit = await context.FindAsync<DocumentAudit>(guid, uid);

return audit.GetDocumentSnapshot();

}

catch (CosmosException ce)

{

if (ce.StatusCode == HttpStatusCode.NotFound)

{

return null;

}

throw;

}

}

Finally, although you can delete a record, the audits remain. The web app doesn’t implement this yet (though it should) but I did implement it in the data service. The steps are simply deserialize the requested version and insert it.

public async Task<Document> RestoreDocumentAsync(

Guid id,

string uid)

{

var snapshot = await LoadDocumentSnapshotAsync(id, uid);

await InsertDocumentAsync(snapshot);

return await LoadDocumentAsync(uid);

}

So far we’re worked backwards from the database through EF Core to an application service. Next, let’s implement the Blazor Server app!

Blazor

I’m a huge fan of Blazor. I am able to quickly build web apps using C# code and logic that would take me much longer to figure out and/or implement in JavaScript. For the rest of this blog post, I assume you are familiar with the Blazor basics and will focus on specific implementation details of the app.

JavaScript Titles and Navigation

Let’s get the JavaScript (mostly) out the way. I know the marketing brochure said no JavaScript but in reality it can be helpful. For example, this code gets a reference to the title tag and updates the browser title for context:

window.titleService = {

titleRef: null,

setTitle: (title) => {

var _self = window.titleService;

if (_self.titleRef == null) {

_self.titleRef = document.getElementsByTagName("title")[0];

}

setTimeout(() => _self.titleRef.innerText = title, 0);

}

}

Of course, I wouldn’t make you call this directly. Instead, I wrap it in a service. The service automatically refreshes the title after a navigation and provides a method to dynamically set it:

public class TitleService

{

private const string DefaultTitle = "Planetary Docs";

private readonly NavigationManager navigationManager;

private readonly IJSRuntime jsRuntime;

public TitleService(

NavigationManager manager,

IJSRuntime jsRuntime)

{

navigationManager = manager;

navigationManager.LocationChanged += async (o, e) =>

await SetTitleAsync(DefaultTitle);

this.jsRuntime = jsRuntime;

}

public string Title { get; set; }

public async Task SetTitleAsync(string title)

{

Title = title;

await jsRuntime.InvokeVoidAsync("titleService.setTitle", title);

}

}

Setting the title from code is then as easy as:

await TitleService.SetTitleAsync($"Editing '{Uid}'");

I also wanted to provide a natural “cancel” feature that returns to the previous page without having to keep my own journal/list of visited pages. It turns out the JavaScript History API is perfect for this. A wrapper to the service looks like this:

public HistoryService(IJSRuntime jsRuntime)

{

goBack = () => jsRuntime.InvokeVoidAsync(

"history.go",

"-1");

}

public ValueTask GoBackAsync() => goBack();

The first page the user is presented with is search.

Search

Search is a common feature. I am often frustrated when I have a perfect set of search results but can’t share the link because the URL forces the user to re-enter search parameters. I designed the app to be bookmark-friendly so you can navigate to practically any page. The NavigationHelper service makes it easy to generate links within the application. For example, the edit link is exposed like this:

public static string EditDocument(string uid) =>

$"/Edit/{Web.UrlEncode(uid)}";

This makes it easy to reference the edit navigation from anywhere in the app, and provides a single place to update it if I ever need to refactor.

Bookmark support

The helper also provides a service to read and write the querystring parameters. Whenever the search parameters are updated, the querystring is regenerated and the app calls navigation:

var queryString =

NavigationHelper.CreateQueryString(

(nameof(Text), WebUtility.UrlEncode(Text)),

(nameof(Alias), WebUtility.UrlEncode(Alias)),

(nameof(Tag), WebUtility.UrlEncode(Tag)));

navigatingToThisPage = false;

NavigationService.NavigateTo($"/?{queryString}");

This does not force a reload, so the navigation flag is set to false to indicate the event is meant to update the browser URL. This allows you to bookmark the search. When you navigate to the full URL, the parameters are parsed and a search is invoked.

var queryValues = NavigationHelper.GetQueryString(

NavigationService.Uri);

var hasSearch = false;

foreach (var key in queryValues.Keys)

{

switch (key)

{

case nameof(Text):

Text = queryValues[key];

hasSearch = true;

break;

case nameof(Alias):

Alias = queryValues[key];

hasSearch = true;

break;

case nameof(Tag):

Tag = queryValues[key];

hasSearch = true;

break;

}

}

navigatingToThisPage = false;

if (hasSearch)

{

InvokeAsync(async () => await SearchAsync());

}

Keyboard support

Keyboard support isn’t just a convenience item. It is important for accessibility as not everyone can use a mouse and for those who aren’t able to use a keyboard, voice software often mimics keyboard gestures. I implemented several specific features for this. The first is updating the tabindex property for natural navigation between fields. When I make a custom control that wraps an HTML form element, I expose a parameter called TabIndex there as well.

The input element I anticipate users will need the most is the text search. I decorate that with autofocus to automate focus there when the form loads. I also use @ref="InputElement" to bind the HTML element to the code-behind that defines it as:

public ElementReference InputElement { get; set; }

After a search completes, I set focus using the newer Blazor feature:

await InputElement.FocusAsync();

So the user can just type and hit ENTER to refine their search. The auto-submit makes it easy to submit the form just by pressing the ENTER key anywhere. I hook into keyboard events on the parent HTML element:

<div @onkeypress="HandleKeyPress">

Handling the key press is as simple as:

protected void HandleKeyPress(KeyboardEventArgs key)

{

if (key.Key == KeyNames.Enter)

{

InvokeAsync(SearchAsync);

}

}

Both tags and authors feature an autocomplete, so I created a generic AutoComplete.razor control. The control also handles the keyboard by hooking into the HandleKeyDown event. The code keeps track of an index into the possible values and highlights the currently selected item. Pressing the up or down arrows increments or decrements the index accordingly.

protected void HandleKeyDown(KeyboardEventArgs e)

{

var maxIndex = Values != null ?

Values.Count - 1 : -1;

switch (e.Key)

{

case KeyNames.ArrowDown:

if (index < maxIndex)

{

index++;

}

break;

case KeyNames.ArrowUp:

if (index > 0)

{

index--;

}

break;

case KeyNames.Enter:

if (Selected)

{

InvokeAsync(

async () =>

await SetSelectionAsync(string.Empty, true));

}

else if (index >= 0)

{

InvokeAsync(

async () =>

await SetSelectionAsync(Values[index]));

}

break;

}

}

A little code can go a long ways!

View

The view page displays the pertinent document information. It also enables an HTML preview. If you try to bind HTML to a control in Blazor, for security reasons it will escape the HTML by default. In earlier versions of Blazor, a workaround was required that involved using some client JavaScript and a textarea element. Fortunately, Blazor now has the MarkupString type that will render as raw HTML.

I implemented an HtmlPreview.razor control to simplify the process of casting HTML text to a MarkupString. The component is fairly straightforward so I won’t spend too much time on it here. Let’s edit our document!

Edits

The edit control uses Blazor’s built-in EditForm combined with a custom validation engine to present the form. I’m not happy with the implementation and plan to refactor it. Although it works, keeping track of multiple validation states is tedious compared to having a single service to manage that. Most of the validations are straightforward. The exception is the markdown field.

The first challenge I had was the size of the field. I was getting “connection lost” and timeout errors whenever I tried to edit it. I tried tweaking the message size for SignalR, but it didn’t work. So, I resorted to another method. I can’t explain why it works, because it should still be using SignalR, but it does.

In essence, instead of directly data-binding the field, I bypass data-binding altogether. I created a special MultiLineEdit.razor control that works with JavaScript to manually data bind. When the field is initialized, this JavaScript is called to render the text in the textarea and listen for changes as the user types:

target.value = txt;

target.oninput = () => window.markdownExtensions.getText(id, target);

The MultiLineEditService generates a unique id to keep track of the session and calls the JavaScript to pass the initial field value.

var id = Guid.NewGuid().ToString();

await jsRuntime.InvokeVoidAsync(

"markdownExtensions.setText",

id,

text,

component.TextArea);

components.Add(id, component);

Services.Add(id, this);

return id;

As the user types, the JavaScript listener calls the service:

getText: (id, target) => DotNet.invokeMethodAsync(

'PlanetaryDocs',

'UpdateTextAsync',

id,

target.value)

The service exposes the method as JsInvokable and routes the changes to the appropriate control.

[JSInvokable]

public static async Task UpdateTextAsync(string id, string text)

{

var service = Services[id];

var component = service.components[id];

await component.OnUpdateTextAsync(text);

}

When the field changes, the editor marks it as invalid pending a user preview. A link button allows the user to generate the preview and this clears the validation error.

I’d be interested in learning why this works as opposed to just data-binding directly. Any thoughts?

Conclusion

My hope in sharing this is to provide some guidance for using the EF Core Azure Cosmos DB provider and to demonstrate the areas it shines. There is work to do, but the good news is we have prioritized updates to the provider for our EF Core 6.0 release. You can help by viewing the issues list and up-voting (click the “like” flag) the issues that impact you the most.

There is plenty of work to be done on this reference project. If you’re looking for an opportunity to contribute to open source, consider grabbing an open issue or entering one of your own. I’m available and happy to help!

Regards,

Related articles: