Play the Chaos Game to Understand WebAssembly Memory Management

A tale of C, fractals, and JavaScript-Wasm Interopability

I’ve been digging into WebAssembly for several weeks now, and one aspect that was difficult for me to understand is how memory is allocated and shared between JavaScript and generated Wasm. There are a few answers scattered across the Internet and simple examples, but I wanted to build something more comprehensive. So, I went back to my roots and tackled the age old “Chaos Game.”

Playing the Chaos Game

I can tell you the exact moment I learned about chaos and fractals. I was on vacation in the late 80’s and our family stayed at a campground somewhere in North Carolina. It was pouring rain, so we were stuck in the cabin. The main lodge had two video games (Donkey Kong and Tempest). I was bored with playing so I decided to browse through the tiny library. One book jumped out at me, entitled “Chaos: The Making of a New Science.” I read it cover-to-cover several times and couldn’t wait to get back home and implement fractals on my Texas Instruments graphing calculator.

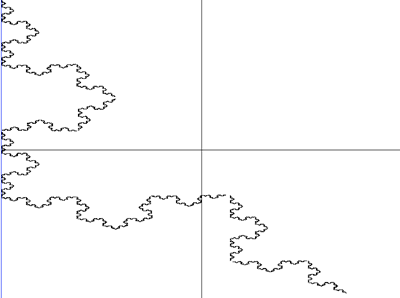

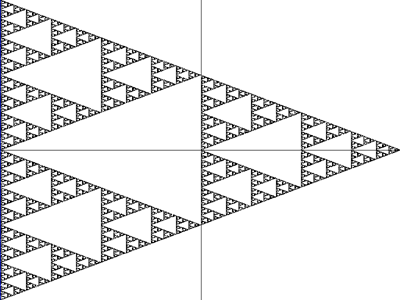

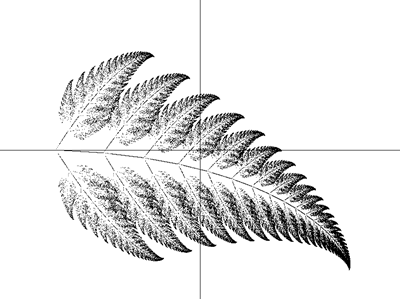

My next purchase was the book “Fractal Programming in C.” Hours later, I was rendering my first fractals. To me, fractals have been a great way to learn new languages. They are based on algorithms so they can be translated to multiple languages, they require array and buffer manipulation to render graphics and provide near immediate feedback and visual gratification. One of the easiest fractals to implement is the chaos game. The chaos game takes in a matrix of values and probabilities, then “rolls the dice” and applies a transformation to a point based on a column of transforms. The results can be stunning.

Top to bottom: Koch curve, Sierpinski triangle, fractal tree, and fractal fern

The chaos game is the perfect way to test WebAssembly’s performance and learn about memory management at the same time.

🔗 Source code: https://github.com/JeremyLikness/wasm-trees

👀 Live demo: https://jlikme.z13.web.core.windows.net/wasm/wasm-trees/

The Challenge

For this challenge, I wanted to learn about memory management and passing buffers between JavaScript and Wasm. My requirements:

- Bi-directional: show I can both pass a buffer into WebAssembly as well as receive one from WebAssembly

- Multiple types and sizes: understand how to access memory holding different types, for example bytes vs. floating point decimal values

- Performance: measure the performance of rendering in Wasm and see if it is practical, for example, to run the examples in a phone browser

Armed with my old books, my knowledge of fractals and WebAssembly and of course the power of search engines, I set forth to implement the chaos game.

I Can “C” Clearly Now

The chaos game operates by holding a matrix of transformations and a probability each will be applied. A point randomly hops around the playing field based on these transformations. The following code sets up the transformations and probabilities for rendering a fractal tree.

void tree()

{

a[0] = 0; a[1] = 0.1; a[2] = 0.42; a[3] = .42;

b[0] = 0; b[1] = 0; b[2] = -0.42; b[3] = 0.42;

c[0] = 0; c[1] = 0; c[2] = 0.42; c[3] = -0.42;

d[0] = 0.5; d[1] = 0.1; d[2] = 0.42; d[3] = 0.42;

e[0] = 0; e[1] = 0; e[2] = 0; e[3] = 0;

f[0] = 0; f[1] = 0.2; f[2] = 0.2; f[3] = 0.2;

p[0] = 1638; p[1] = 6553; p[2] = 19660; p[3] = 32767;

xscale = width * 2;

yscale = height * 2;

xoffset = width / 2;

yoffset = 0;

}The p values are a scale of probability. If I roll a 32768-sided die, it will fall under one of the columns and that is what I use for the transformation.

The Evolution of the Integer: My first attempt to adapt some old C code to WebAssembly failed horribly. Any attempt I made would only render a few points. It was then I realized I was using

intand callingrand()to generate a value. The probabilities are staggered from 0 through 32767 which are the positive values for a signed 16-bit integer. That was fine in 1989, but today integers by default are 32-bit and allow an order of magnitude more values. So, I had to modify the probability by usingrand() % 32768.

The main algorithm to play the game simply iterates (in my case 99,999 times) and plots the point wherever it lands. This is the code to play the game.

int px, py;

float x = 0, y = 0;

for (int i = 0; i <= 99999; i++)

{

int j = rand() % 32678;

int k = (j < p[0]) ? 0 : ((j < p[1]) ? 1 : ((j < p[2]) ? 2 : 3));

float newx = (a[k] * x + b[k] * y + e[k]);

y = (c[k] * x + d[k] * y + f[k]);

x = newx;

px = x * xscale + xoffset;

py = y * yscale + yoffset;

plot(px, py, 0x01);

}That simple amount of code — the seeded values and the iterator — are all that is needed to produce the graphics depicted earlier. Pretty powerful! The scale and offsets are values I experiment with to render the graphic correctly inside of the view port. I wrote the code so an unsigned byte buffer is passed in (this allows me to pre-render grid lines in JavaScript and show that I can pass an array into WebAssembly), along with the width and height of the “playing field”, and two flags. One flag initializes the model with one of the preset matrices: tree, fern, triangle, maze, and Koch curve. The other flag, called “distort” simply nudges a random transformation in one direction. By using this flag, I can animate the changes that occur when the values change.

This is the method declaration and the code to “nudge” the matrix.

unsigned char *renderTree(unsigned char *buf,

unsigned int inHeight, unsigned int inWidth, int model, int distort)

{

printf("RenderTree %d %d %d %d\n", inHeight, inWidth, model, distort);

buffer = buf;

height = inHeight; width = inWidth;

minx = 32768; maxx = -32768; miny = 32768; maxy = -32768;

if (distort == 1)

{

float *arr;

int which = rand() % 6;

switch (which)

{

case 0:

arr = &a[0];

break;

case 1:

arr = &b[0];

break;

case 2:

arr = &c[0];

break;

case 3:

arr = &d[0];

break;

case 4:

arr = &e[0];

break;

default:

arr = &f[0];

}

int direction = rand() % 2 == 0 ? -1 : 1;

int idx = rand() % 4;

arr[idx] += 0.005 * direction;

}

}Notice a pointer to a buffer is passed in. That pointer is also passed back to JavaScript at the end with return &buffer[0]; The printf statement gets mapped to console.log. I also track bounds for plotted points, capturing the minimum and maximum values passed even if they fall outside of the view port. This helped me adjust the appropriate scales and offsets for rendering purposes.

The plot method simply does some bounds checking and if the point is in bounds, renders it by setting a byte in the buffer:

buffer[x * height + y] = color;

Because the code mutates the matrix of values, I want a way to pass those values back to JavaScript to display on screen (this way if you end up with an amazing new fractal, you can freeze the frame and save the values for later). The matrix is a set of arrays:

float a[4], b[4], c[4], d[4], e[4], f[4];

The addresses of those arrays can be stored in an array of pointers:

float *addresses[6];

The getAddresses method sets the pointers and then returns the array of memory addresses. Notice it uses the ** format “pointer to pointer”.

float **getAddresses()

{

addresses[0] = &a[0];

addresses[1] = &b[0];

addresses[2] = &c[0];

addresses[3] = &d[0];

addresses[4] = &e[0];

addresses[5] = &f[0];

return &addresses[0];

}All the code is available online in this GitHub repository.

The next step is to compile the C code to WebAssembly.

Compiling C to Wasm

Emscripten is a set of tools created specifically to compile C/C++ projects to WebAssembly. In addition to generating Wasm byte code, it provides other services such as mapping standard output to the JavaScript console and converting JavaScript types when passed as parameters to C and C++ functions. The SDK has tools to install and/or build it on multiple platforms, but my preference is to use a pre-built Docker container. This allows me to use the tools without installing anything locally.

Included in the project are two “helper” scripts in the tools folder for building the WebAssembly. They should be run from the src directory, like this: ..\tools\compile.bat or ../tools/compile.sh. The main command looks like this for Windows:

docker run -it --rm -v %cd%:/src trzeci/emscripten emcc trees.c -O2 -s WASM=1 -s EXPORTED_FUNCTIONS="['_renderTree', '_getAddresses']" -s EXTRA_EXPORTED_RUNTIME_METHODS="['ccall','cwrap']" -o trees.js -s ALLOW_MEMORY_GROWTH=1

The bash shell version is almost identical except for the convention to get the current working directory. This is a breakdown of the parameters:

run— tells Docker to run the specified image. It will download it if it’s not already available locally.-it— runs interactively in “terminal” mode, so you will see the output of executed commands.--rm— removes the Docker container automatically when it’s done running.-v— mounts storage for the container. The convention after maps the current working directory on the host machine to thesrcfolder in the container. This allows the Emscripten tools to “see” the current working directory.trzeci/emscripten— points to this pre-configured Docker container with the SDK and tools.emcc—runs the Emscripten compiler.trees.cis passed as the file to compile.-O2—optimizes the output. There are several optimization options, and this is the most effective that preserves the utilities for memory management.-s WASM=1—informs the compiler to output WebAssembly. Use 0 to emit asm.js instead.-s EXPORTED_FUNCTIONS— exposes functions from the C code to the JavaScript module that is generated. If the functions aren’t specified, the compiler has no way of knowing they will be called, and they end up optimized out of the generated Wasm.-s EXTRA_EXPORTED_RUNTIME_METHODS—indicates what “helper” functions provided by Emscripten are included. The functions listed help convert parameters when calling from JavaScript into Wasm and vice versa. More on those later.-s ALLOW_MEMORY_GROWTH=1—generates memory management code to allocate bytes from JavaScript that can be passed to WebAssembly.-o trees.js— indicates that a “wrapper” JavaScript file to load and expose the WebAssembly should be generated.

Running this command should create two files around 20 kilobytes in size each: trees.js and trees.wasm. The scripts will also copy these into the web directory.

Pass Data and Call Functions from JavaScript

The main JavaScript code (written, not generated) lives in index.js. There you will find a variable set to track state, references to the canvas, and several functions that are called on intervals or based on events. The first “Wasm-related” bit of code looks like this:

const renderTree = Module.cwrap("renderTree", "number", ["array", "number", "number", "number", "number"]);

const loadValues = Module.cwrap("getAddresses", "number", []);The cwrap call is aptly named: it wraps a call to a C function in a JavaScript function. It’s not a requirement (you could use Module._renderTree directly instead) but approaching it this way ensures proper type conversion. More importantly, it also allows you to pass arrays into WebAssembly. The parameters, in order, are the function name, the return value, and the types of the parameters passed in. Let’s look more closely at renderTree for a moment. Notice the first parameter is of type “array.”

In this scenario, a buffer is created in JavaScript that is passed to Wasm and used as a “canvas” to plot points on. To show it is successfully passed in, a set of grid lines are “drawn” in JavaScript. This code creates the array and populates the grid lines.

let typedArray = new Uint8Array(width * height);

const mid_x = width / 2;

const mid_y = height / 2;

for (let x = 0; x < width; x += 1) {

for (let y = 0; y < height; y += 1) {

typedArray[mid_y * width + x] =

typedArray[y * width + mid_x] = 1;

}

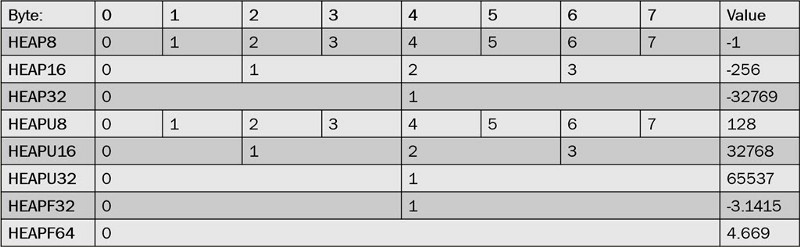

}There are two steps needed to pass in the array. First, memory must be allocated in WebAssembly to receive the buffer. Second, the buffer must be copied into Wasm. For convenience, WebAssembly exposes its memory based on contiguous blocks, or heaps, of typed data. For example, Module.HEAPU8 exposes the heap of unsigned bytes. Module.HEAPF32 exposes a memory block that contains 32-bit floating-point numbers. The buffer we’ll be using, specified as unsigned char * in the C code, is unsigned bytes and therefore it is the unsigned byte heap we use.

The following code allocates the memory and copies the JavaScript array into the memory. It then passes the array directly using the wrapped function call, that in turn will find the pointer to the array in the heap and pass that into the C function. After parsing the returned value, the allocated memory is freed.

let buffer = Module._malloc(typedArray.length * typedArray.BYTES_PER_ELEMENT);

Module.HEAPU8.set(typedArray, buffer / typedArray.BYTES_PER_ELEMENT);

let offset = renderTree(typedArray, width, height, model, distort);

Module._free(buffer);The key here is to note even though

typedArrayis passed to the function, it is a wrapped call. What is actually passed to the C code is a pointer toHEAPU8that was created in the earliersetoperation.

Notice that it is important to allocate the right memory size and pass the correct pointer. In this case, the math is a bit redundant because there is exactly one byte per element. Keeping this formula in mind and consistently using the built-in constants for element sizes will ensure you always allocate and set the memory correctly. You multiply by bytes per element (for example, a 16-bit integer would have two bytes per element) to allocate memory, and divide by bytes per element to set the memory pointer.

At this stage, you can observe a few interesting behaviors:

- Any manipulation of the memory is not reflected in the original

typedArrayinstance. You can inspect the array after the call and find it is unchanged. It is used to transfer data into the Wasm heap. - The offset created by allocating memory is not the same offset that is passed back. The memory given to C is separate and must be passed back for access. Therefore, the

bufferoffset is not used to read the altered bytes; instead, a new pointer is passed back into theoffsetvariable.

Next, let’s read some memory from WebAssembly.

Read WebAssembly Memory from JavaScript

The most straightforward way to read Wasm memory is to use the unsigned byte heap. The following code successfully parses the buffer that was manipulated by WebAssembly and uses it to construct image data that is drawn on the canvas. Note that it simply iterates through the heap starting at the offset that was passed back from the C code (see line 3).

let imageBuffer = new Uint8ClampedArray(width * height * 4);

for (let idx = 0; idx < typedArray.length; idx += 1) {

let color = Module.HEAPU8[offset + idx];

if (color != 0) {

let pos = idx * 4;

imageBuffer[pos] = imageBuffer[pos + 1] = imageBuffer[pos + 2] = color;

imageBuffer[pos + 3] = 255;

}

}

let imageData = new ImageData(imageBuffer, width, height);

ctx.putImageData(imageData, 0, 0);That’s great, but what about other types of memory? If you recall, the C code holds several floating-point arrays of data used for transformations. The getAddresses method returns a pointer to an array of pointers that each point to arrays of floating-point numbers.

What?!

Let’s deconstruct that by looking at the getValues function.

let variables = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f'];

const ptr = loadValues();

let str = 'Variables:';

variables.forEach((val, idx) => {

const varOffset = Module.HEAPU32[ptr / Uint32Array.BYTES_PER_ELEMENT + idx];

str += "\n";

for (let i = 0; i < 4; i += 1) {

const value = Module.HEAPF32[varOffset / Float32Array.BYTES_PER_ELEMENT + i];

str += `${val}[${i}]=${value.toFixed(2)} `;

}

});

return str;The data passed back is an array of pointers. Pointers are unsigned 32-bit integers, so the heap is parsed by computing an offset into HEAPU32 using the pointer passed back by the loadValues (mapped to getAddresses) call:

const varOffset = Module.HEAPU32[ptr / Uint32Array.BYTES_PER_ELEMENT + idx];

Notice the pointer is divided by the size of the array elements before being indexed.

The

HEAPxxtypes overlay the same memory. They are just different typed views into a singleArrayBuffer.

Each pointer retrieved is a pointer to a floating-point array. Therefore, the second pointer value is used to reference memory in HEAPF32. We know each floating-point array has four elements, so an inner loop iterates through those values. The key, again, is to divide the pointer by the size of the elements to index the actual offset in memory.

const value = Module.HEAPF32[varOffset / Float32Array.BYTES_PER_ELEMENT + i];

Logically, the layout looks like this:

HEAP overlays

Let’s assume you want to reference an array of two unsigned 16-bit integers starting at memory location 4. The pointer is always a byte-aligned pointer, so “4” really means position “2” in the HEAPU16 (4 / 2 = 2). This code will do the trick:

const ptr = Module.getOffset(); // assume this passes the mem addr (4) const jsArray = new Uint16Array(Module.HEAP16, ptr/Uint16Array.BYTES_PER_ELEMENT, 2);

After grabbing the values from memory, the function then emits these values so you can capture them for later reference.

Conclusion

This project focuses on how WebAssembly and JavaScript work together to manage and access memory. Hopefully, this provides a solid understanding of the Wasm memory model, how to wrap functions for calls, and how to correctly access memory from JavaScript. Before I conclude, I don’t want to lose sight of the magic that is happening.

🔗 Source code: https://github.com/JeremyLikness/wasm-trees

👀 Live demo: https://jlikme.z13.web.core.windows.net/wasm/wasm-trees/

When you run the application, you can open the browser debug console and view some statistics emitted by the code. For example, the buffer offset passed into render tree is shown, along with the pointer passed out. Notice how different they are! But more important, look at how long it takes to render the graphic. Each “frame” performs 99,999 iterations of a floating-point matrix transformation, and on my machine, it runs in less than 10 milliseconds. It also doesn’t appear to skip a beat when rendered on my phone. In my opinion that stands as a testament to not only how far compute power has come, but also how practical it is to run code today in the global, standard, secure operating system known as your web browser.

Regards,

Related articles:

- Build a Blazor WebAssembly Line of Business App Part 3: Query, Delete and Concurrency (Webassembly)

- Build a Single Page Application (SPA) Site With Vanilla.js (JavaScript)

- Explore WebAssembly System Interface (WASI for Wasm) From Your Browser (Wasm)

- Getting Behind the 9-Ball: Cosmos DB Consistency Levels Explained (Programming)

- Implement a Progressive Web App (PWA) in your Static Website (JavaScript)

- What the Shard? (Programming)