Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0 Part 4: Optimistic Concurrency

Authoring APIs that respect change

Part of the series: Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0

This is the fourth part in a multi-part series on Web API design. Here is the full list for easy navigation:

- Intro and Content Negotiation

- HATEOAS

- Exceptions

- Concurrency (currently reading)

- Security

- Bonus (because I said it would be five): Swagger

Most API implementations are stateless — you can think of them as having no memory. The payload that is passed to the API contains everything needed for the process to complete successfully. That’s all fun and games until you sign up your second user or your one existing user opens the app in a separate tab. Now you’re on the hook to handle concurrency.

Imagine Tristan and Iseult are working from the same task list. They both read the list at the same time, and it has exactly one entry:

“Take the clean dishes out of the dishwasher.” — Incomplete

Two things happen at the same time. Iseult decides that it is important not only to take the clean dishes out, but to put the dirty dishes back in. So she sends an update that looks like this:

“Take the clean dishes out of the dishwasher, then put the dirty dishes in.” — Incomplete

At the same time, Tristan has finished emptying the dishwasher so he marks the task complete because he is totally unaware of Iseult’s change. His update looks like this:

“Take the clean dishes out of the dishwasher.” — Complete

Oops. Now there’s a problem!

The two main methods for tackling concurrency are pessimistic and optimistic concurrency. If you’re a pessimist, you assume the worse: everyone is going to be stomping over each other all of the time.

Instead of allowing anyone to update the task, you implement a system with locks. Anyone can read a task, at any time. However, when someone wants to update a task, they must first obtain an exclusive lock. The first person to acquire the lock wins, and no one else is able to make any changes until the lock is released. That narrative looks like this:

Iseult and Tristan both read the task.

Iseult locks the task to update it.

Tristan attempts to lock the task to update it, but can’t, because Iseult has the lock.

Iseult updates the task then releases the lock.

Tristan has to refresh his task to see if the lock is released. When he does, he realizes there is more to do. Eventually he, too, locks and updates the task.

In reality, most systems don’t experience truly concurrent updates so often, and implement optimistic concurrency. As an optimist, you assume that most of the time, the task hasn’t changed since you last looked at it, so your update should be valid. However, in the rare case it has changed, you are given the chance to either redo your changes or force the update. It goes something like this:

Iseult and Tristan both read the task.

Iseult updates the task.

Tristan tries to update the task, but the system recognizes that the copy he is trying to update is old and stale. Tristan is informed that the task has changed, and given the option to force his update or refresh the changes.

Tristan refreshes, and sees the task has changed. He takes appropriate action, and everyone is happy.That all sounds great, but how do you implement in code? It’s actually quite easy. In fact, web APIs typically leverage the same mechanism that web browsers have used for caching pages since 1999. The method uses special values known as entity tags. The server should return an ETag value for the requested page that the browser can store as part of the cache. The next time the page is requested, the browser sends the ETag back. If the content hasn’t changed, the server returns a 304 — not modified response code. Otherwise, the new content (and ETag) is returned.

For REST APIs, the URL refers to the data you are dealing with. You can generate an ETag for the data several ways:

- Use a field that auto-updates anytime a record is modified, like SQL Server’s

[rowversion](https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/sql/t-sql/data-types/rowversion-transact-sql) - Generate and store a unique value, such as a GUID, any time the record is modified

- Compute a hash tag from the data that has a low likelihood of collision (i.e. the same value for two different data points)

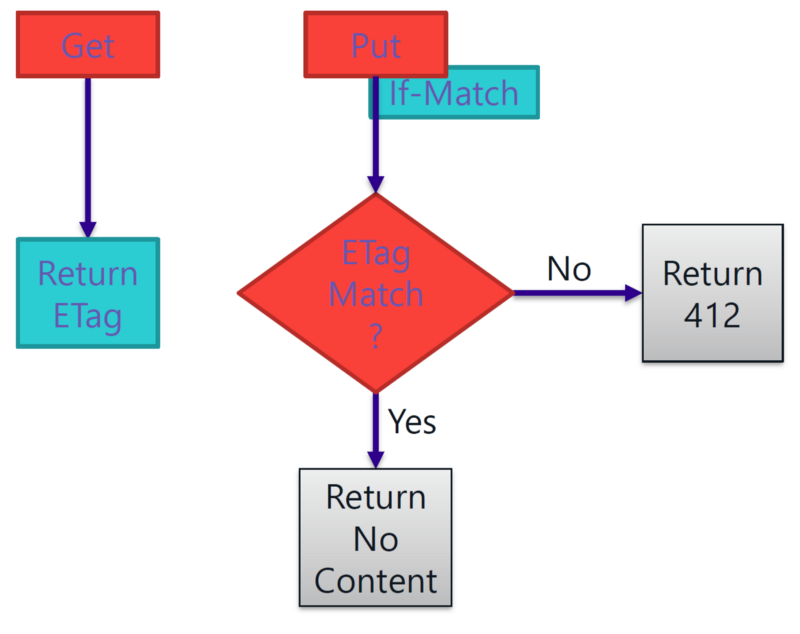

The server should return the ETag as part of the response header, and the client should include it in the If-Match header when performing updates. When the tags don’t match, implying the data has changed since the client last fetched it, the server returns a failure code (412 — precondition failed) and does not perform the operation. The client can then fetch the newer version and prompt the user to refresh or overwrite the changes.

To help illustrate this, I tapped into my shallow well of artistic ability to create this brilliant diagram.

In our simple “to do list” application, the individual data items don’t have a GUID or time stamp, so I implemented a primitive hash function that combines the id, status, and text of the task to create a string. I use the message-digest algorithm to generate a 128-bit hash code and return its hexadecimal value.

This is just one example. To avoid the overhead of computing a hash every time, the easiest approach is to use a built-in database mechanism, like a row version, high precision time stamp, or GUID.

var itemText = $"{item.Id}|{item.IsComplete}|{item.Name}";

using (var md5 = MD5.Create())

{

byte[] retVal = md5.ComputeHash(Encoding.Unicode.GetBytes(itemText));

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (int i = 0; i < retVal.Length; i++)

{

sb.Append(retVal[i].ToString("x2"));

}

return sb.ToString();

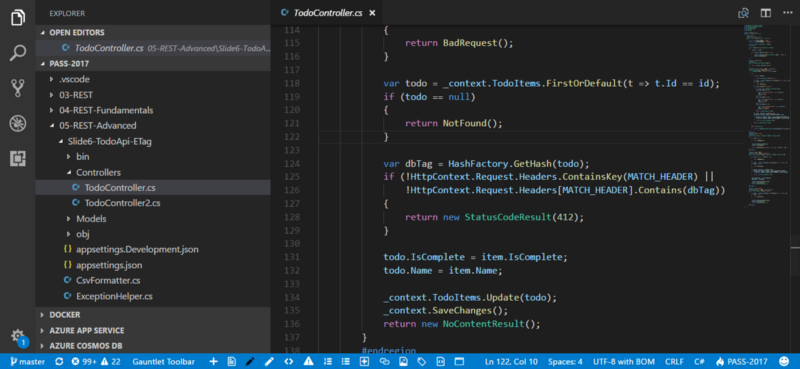

}The controller always returns the hash in the ETag header value.

var eTag = HashFactory.GetHash(item);

HttpContext.Response.Headers.Add(ETAG_HEADER, eTag);When the client sends an existing value using the If-Match header and the hash code hasn’t changed, the controller returns the “not modified” response code with no body.

if (HttpContext.Request.Headers.ContainsKey(MATCH_HEADER) &&

HttpContext.Request.Headers[MATCH_HEADER].Contains(eTag))

{

return new StatusCodeResult(304);

}Finally, the update operation expects an If-Match header to exist. If the header doesn’t exist, or if it doesn’t match the current hash code, it returns the error status.

var dbTag = HashFactory.GetHash(todo);

if (!HttpContext.Request.Headers.ContainsKey(MATCH_HEADER) ||

!HttpContext.Request.Headers[MATCH_HEADER].Contains(dbTag))

{

return new StatusCodeResult(412);

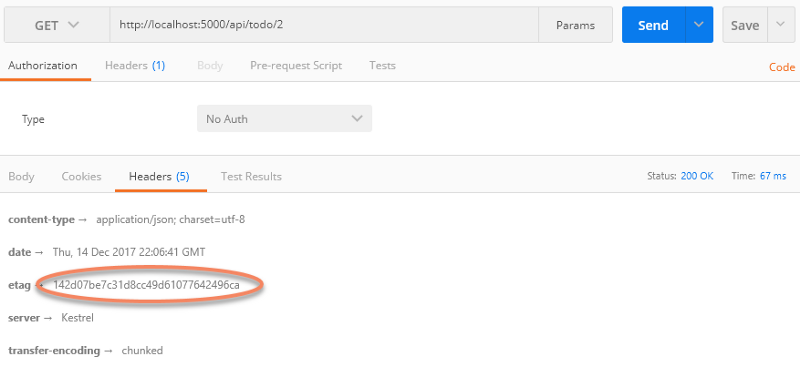

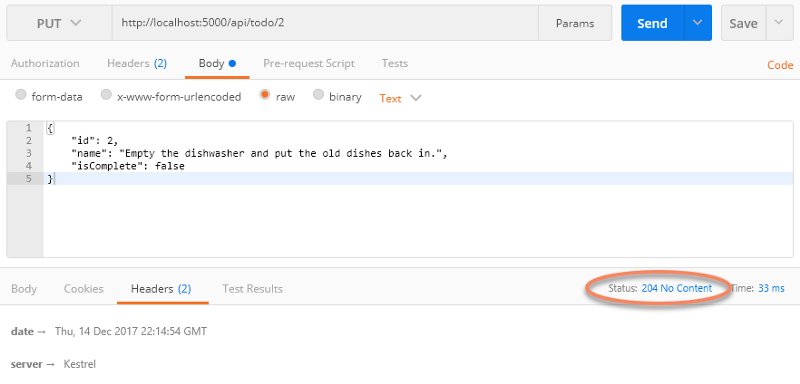

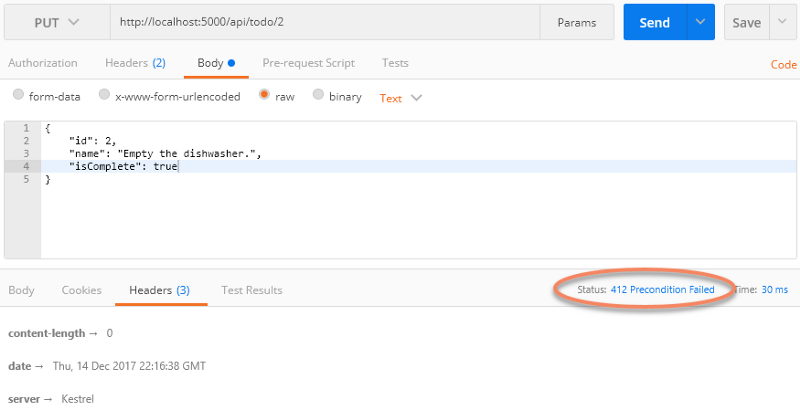

}Now Tristan and Iseult’s story unfolds, as told by Postman and ASP. NET Core 2.0 Web API:

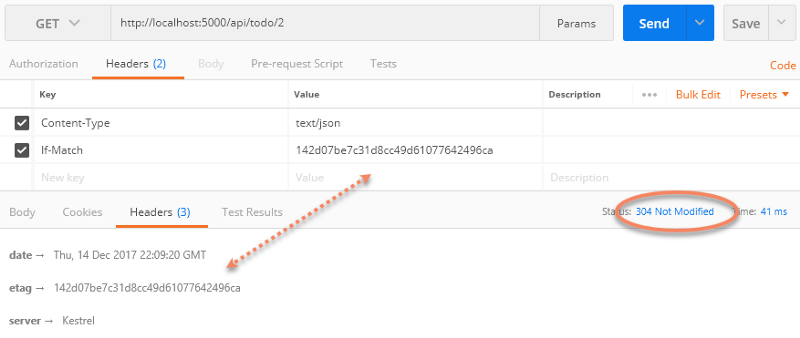

Notice that an ETag is returned. Let’s assume for the sake of argument that Tristan wanted to be sure nothing changed, so he requested it again with the If-Match header set to the hash value.

Finally, Tristan is able to refresh the task to obtain the updates along with the correct ETag and eventually close the loop. That concludes our grand tale of optimism.

But wait! There’s more …

Easy navigation:

- Intro and Content Negotiation

- HATEOAS

- Exceptions

- Concurrency (currently reading)

- Security

- Bonus (because I said it would be five): Swagger

Regards,

Part of the series: Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0

- Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0 Part 1: Content Negotiation

- Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0 Part 2: HATEOAS

- Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0 Part 3: Exceptions

- Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0 Part 4: Optimistic Concurrency

- Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0 Part 5: Security

- Five RESTFul Web Design Patterns Implemented in ASP.NET Core 2.0 Bonus: Swagger