JSON and the MongoDB Driver for the .NET Developer

Tips for using the C# MongoDB Driver with examples using CosmosDB and .NET Core 2.0.

Recently I created a .NET Core 2.0 project to demonstrate several features of CosmosDB. I chose the MongoDB driver due to its popularity and because I’m already familiar with it through my Node.js work. As a C# developer, I love that I can create strongly-typed domain objects and work with “known entities” as part of my application. Paradoxically, as a JavaScript developer I love the dynamic flexibility that JSON documents provide. Believe it or not, it’s possible to have the best of both worlds.

To keep things simple and provide a meaningful demo, I chose to work with the freely available USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. This database contains lists of foods, food groups, and other nutrient data that you can query for information like protein content and total calories using different weights and measures. The files are well-documented and relatively easy to parse. I built an application to import them into CosmosDB that I’ll share in a follow-up post after I present my CosmosDB talk.

The Strongly Typed World

The key component of the USDA database that I am interested in is the individual food items. Each food item has one or more weights or “units of measure” associated with it (think: tablespoons vs. cups or dry vs. cooked) and a list of nutrient information. Some foods in the database only have a few entries for nutrient information, while others may have several hundred values. My first pass at a class definition looked like this:

public class FoodItem

{

public string FoodId { get; set; }

public string FoodGroupId { get; set; }

public FoodGroup Group { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public string ShortDescription { get; set; }

public string CommonNames { get; set; }

public string Inedible { get; set; }

public Weight[] Weights { get; set; }

public Nutrient[] Nutrients { get; set; }

}One benefit of document databases is that you aren’t constrained by foreign key relationships and can embed other nested documents as needed. In this case, although I created a separate collection (think of collections as tables in traditional relational databases) for the nutrient definitions, I also store them directly on the “FoodItem” in the “Nutrients” array as a property of the “Nutrient” class. This makes it easy to access values because once I load the food item, all of the related information (or “navigation properties”) is already there.

I started building a set of APIs to access the data and immediately ran into a problem. It is important to be able to query food items by content. You might want to ask a question like, “What foods have the most protein by weight?” or, if you follow a 100% plant-based diet like I do, “What foods in the nuts and seeds group have the most calcium by weight?”

The problem with the class as defined above is that the nutrient information is stored as an array. There is no predefined “slot” for a given nutrient, so any type of sort requires a sub-query across the nutrients list to find the right amount. Even a query designed to grab the top 20 records has to scan every single document (and there are almost 9,000 of them) in order to find the nutrient amounts. The database can’t build an index over the information because of the way it is defined. The “top nutrients” query took over 30 seconds to run and often timed out with too many requests.

I needed a different approach.

The Dynamically Typed World

To solve the problem, I chose to take advantage of the fact that CosmosDB is a document database that doesn’t force the documents into a specific schema. Instead, I am able to store the data in whatever way makes it easier to query. To do this, I decided to move the nutrients from an array to direct properties of the document in the database. Instead of this:

{

foodItem: 'Purple pancakes',

nutrients: [

{ name: 'protein', amount: 100 },

{ name: 'carbohydate', amount: 1000 }

]

}The document is stored like this:

{

foodItem: 'Purple pancakes',

nutrients: {

protein: { amount: 100 }

carbohydrate: { amount: 1000 }

}

}The difference is subtle but powerful. Now I can build a query to sort by “nutrients.protein.amount descending” without using an inner query or having to scan all of the documents. The database is able to generate the appropriate index because it’s a navigable property on the document. Of course, my client is still written in C#. How do I handle the dynamic type?

MongoDB.BSON to the Rescue!

Behind the scenes, documents are stored in a binary-serialized version of JSON to reduce space and improve performance. The MongoDB driver for C# includes a powerful library for manipulating BSON documents and values.

BSON is short for “binary-serialized JSON.”

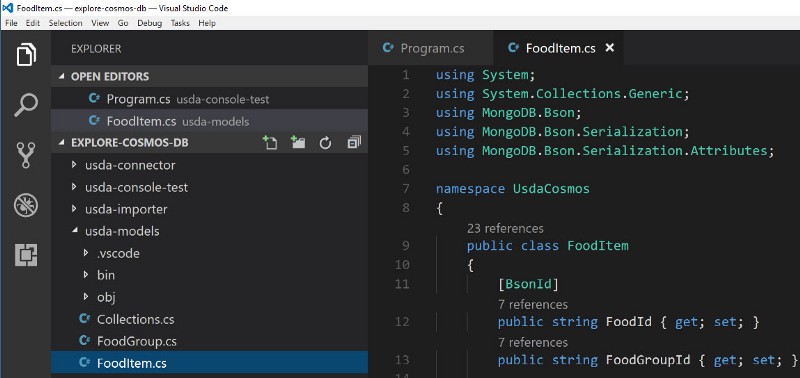

Although I could have easily taken the approach to work entirely with BSON-style documents (think of it as “dynamic types” in C#), I chose the approach that I believe provides the best of both worlds. First, I updated the class definition to include the BSON library and added a few attributes and a new property. The new class looks like this:

public class FoodItem

{

[BsonId]

public string FoodId { get; set; }

public string FoodGroupId { get; set; }

public FoodGroup Group { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public string ShortDescription { get; set; }

public string CommonNames { get; set; }

public string Inedible { get; set; }

public Weight[] Weights { get; set; }

public BsonDocument NutrientDoc { get; set; }

[BsonIgnore]

public Nutrient[] Nutrients { get; set; }

}The “BsonId” attribute specifies that the “FoodId” property is the unique identifier for the document. The “BsonIgnore” attribute informs the driver not to serialize the values in the “Nutrients” array. Instead, a new property of type “BsonDocument” is exposed that is essentially a sub-document to contain the nutrient information. I still deal with the class as a strongly-typed domain object in C#, but when I’m ready to serialize it, I call a helper method that transfers the nutrition information into the document property.

public void SerializeNutrients()

{

var root = new BsonDocument() { {"nutrients", new BsonDocument()} };

foreach (var nutrient in this.Nutrients)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(nutrient.Definition.TagName))

{

continue;

}

root["nutrients"][nutrient.Definition.TagName] =

new BsonDocument() {

{"id", nutrient.NutrientId},

{"amount", nutrient.AmountInHundredGrams},

{"description", nutrient.Definition.Description},

{"uom", nutrient.Definition.UnitOfMeasure},

{"sortOrder", nutrient.Definition.SortOrder}

};

}

this.NutrientDoc = root;

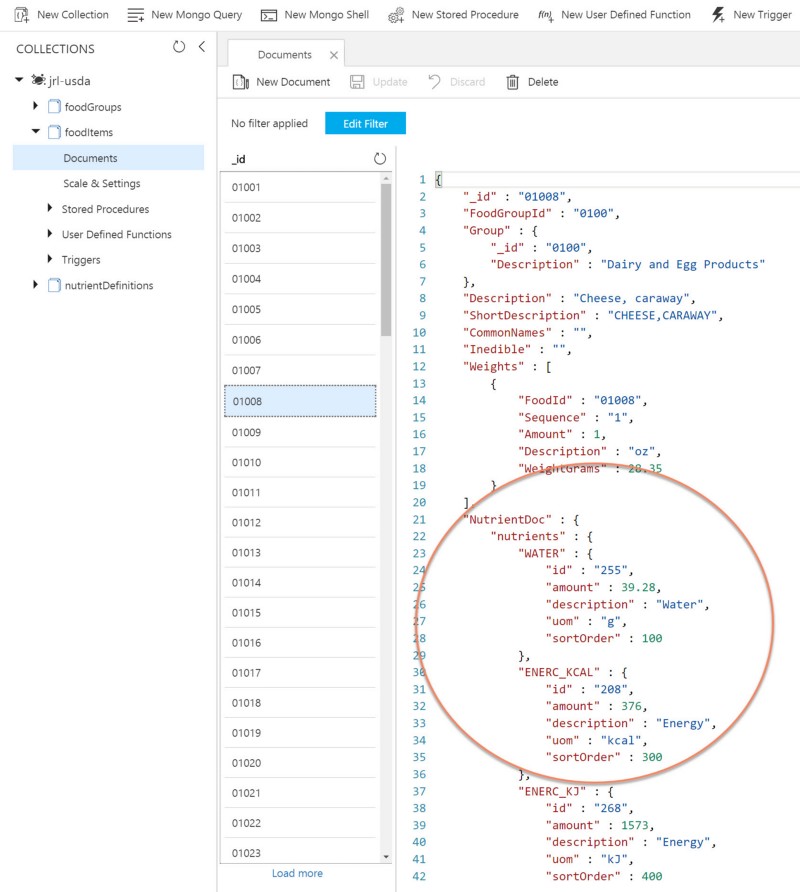

}The resulting document looks like this in raw JSON format (courtesy of the browser-based CosmosDB data explorer):

Loading a document from the database only populates the document property, so I also wrote a helper method that iterates the available nutrients and rebuilds the nutrient array. It also supports filtering to a specific nutrient tag.

public void DeserializeNutrients(string tag = null)

{

var elements = this.NutrientDoc["nutrients"].AsBsonDocument;

var list = new List<Nutrient>();

foreach (var element in elements.Elements)

{

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(tag)) {

if (element.Name != tag) {

continue;

}

}

var nutrient = new Nutrient

{

FoodId = this.FoodId,

NutrientId = element.Value.AsBsonDocument["id"].AsString,

AmountInHundredGrams = element.Value.AsBsonDocument["amount"].ToDouble(),

Definition = new NutrientDefinition

{

NutrientId = element.Value.AsBsonDocument["id"].AsString,

UnitOfMeasure = element.Value.AsBsonDocument["uom"].AsString,

Description = element.Value.AsBsonDocument["description"].AsString,

TagName = element.Name,

SortOrder = element.Value.AsBsonDocument["sortOrder"].AsInt32

}

};

list.Add(nutrient);

}

this.Nutrients = list.ToArray();

}Pro Tip: even though the “amount” property is a double, the BSON serialization engine assumes it is an integer when the value is a whole number. Therefore, an “AsDouble” cast will fail. The solution is to use “ToDouble” instead, so it can cast any integer values to double as needed.

The final step is the query itself. Similar to using an Object-relational mapper (ORM), the MongoDB driver makes it possible to project documents directly onto strong types. Here are the steps for a strongly-typed query:

- Use the strongly-typed “FoodItem” class but only bring the “FoodId,” “FoodGroupId,” “Description,” and “ShortDescription” properties back from the server to save bandwidth

- Use the “foodItems” collection

- Find the first 100 food items that match the search filter

- Iterate the result list asynchronously

Here is the code:

var projection = Builders<FoodItem>.Projection

.Include(fi => fi.FoodId)

.Include(fi => fi.FoodGroupId)

.Include(fi => fi.Description)

.Include(fi => fi.ShortDescription);

var query = db.GetCollection<FoodItem>(Collections.GetCollectionName<FoodItem>());

var findFluent = query.Find(fi => fi.Description.Contains(search));

var projectedQuery = findFluent.Limit(100).Project(projection);

await projectedQuery.ForEachAsync(item => { // do something });

What about dynamic queries? Instead of using the strongly typed C# class, dynamic queries use the more dynamic “BsonDocument” type to specify sorts and projections. Here’s the code to find the top 100 items sorted by highest amount of a specific nutrient based on its tag.

var sort = Builders<BsonDocument>.Sort.Descending($"NutrientDoc.nutrients.{tag}.amount");

var projection = Builders<BsonDocument>.Projection

.Include("_id")

.Include("FoodGroupId")

.Include("ShortDescription")

.Include("Description")

.Include($"NutrientDoc.nutrients.{tag}");

var query = coll.Find(_ => true)

.Project(projection)

.Sort(sort)

.Limit(100);

await query.ForEachAsync(fi => { // do something });

Note that the only difference in the results is that each item is a “BsonDocument” instead of a “FoodItem” but can easily be cast/transformed from one to the other.

Regardless of the property name you use for the unique identifier in your C# model, the database will always internally store the identifier property with the name “_id”.

The refactored query returns results in milliseconds instead of timing out as it did before.

Putting it all Together

As developers it’s important to recognize when we are trying to solve the wrong problem. I spent a day trying to optimize the sub-query that scanned the nutrients by amount before I realized I was approaching a document database problem with a relational-database mindset. The solution wasn’t to keep hammering at the query, but instead to take advantage of the nature of the document database and store the documents differently.

In a way, object-relational mappers (ORM) tools like Entity Framework Core provide a similar solution. The ORM maps a relational entity to a domain entity, whereas the solution I detailed here maps a dynamic document-based entity to a strongly-typed domain entity. The result is the difference between queries lasting seconds or minutes and taking only milliseconds to complete.

The driver and tips here will work with any Mongo compatible database. If you want to stand up your own database quickly in the cloud that is capable of scaling to massive workloads and can geo-replicate across the globe with the click of a button, take a look at CosmosDB. If you have other tips and tricks for dealing with document databases in C#, leave them in the comments below!

Thanks,

Related articles:

- Inspect and Mutate IQueryable Expression Trees (.NET Core)

- Managing Data 📈 in the Cloud ☁ (Mongodb)

- NoSQL and Azure Cosmos DB in 20 Minutes (Cosmosdb)

- Play the Chaos Game to Understand WebAssembly Memory Management (Programming)

- Say “Yes” to NoSQL for .NET SQL Developers (Mongodb)

- Using LINQ to Query Dynamic Schema-less Cosmos DB Documents (NoSQL)