.NET Core 2.0 is Ready and Sterling Proves It!

Learn about the features available in .NET Core 2.0 via the Sterling port that depends on binary serialization, reflection, and more.

The challenge of creating a programming model that enables you to share the same code across platforms has existed since computers were invented. Did you know that a virtual machine was created in 1979 that ran on personal computers and was called the “Z-Machine?” When I began building enterprise applications in the 1990s, everyone was confident the perfect Computer-aided Software Engineering (CASE) tool was just around the corner. The main reason I was a strong supporter of Silverlight is because of its promise to enable me to write code once and run it anywhere.

Those dreams were dashed when competitors who happened to produce the most popular smartphones refused to adopt the platform.

Every couple of months the rumours about Silverlight and the iPhone heat up. Get over it people, it's never going to happen.

— Justin Angel (@JustinAngel) June 3, 2010

wanna port WP7 game to iPhone/Android but Joseph fron MonoTouch replied that there is no active plan to support Silverlight yet.. :-/

— Michael Sync (@michaelsync) September 24, 2010

The project Michael referred to, Mono, was launched in 2001 with a goal to bring the .NET framework to Linux. It has a long and fascinating history which I’ll skip here but is easy to find online if you’re interested in learning more. To make a short story boring, the technology eventually led to a product named Xamarin that was acquired by Microsoft in 2016, a full 15 years after the original project began.

Microsoft to acquire Xamarin: https://t.co/brtUL8SxEy pic.twitter.com/h5pvm7SibT

— SD Times (@sdtimes) February 29, 2016

Xamarin empowers developers to create cross-platform mobile apps, but what about Linux? Around 2011 Twitter exploded with discussion about a new framework cleverly named, well, .NET Core. Microsoft announced that the new, truly cross-platform version of .NET would be written from the ground up. Some people wondered why Microsoft bothered preserving the .NET name, but the team was adamant they would support well-known .NET APIs. A few years later, .NET Core was open sourced.

Posted: .NET Core is Open Source -- http://t.co/v7aUFRd4j4

— .NET (@dotnet) November 12, 2014

And finally, in 2016, five years after the online mumbling about this new core thing began, the first “production” version was released.

Announcing .NET Core 1.0 RTM! https://t.co/D3aDhverVn #dotnetcore

— .NET (@dotnet) June 27, 2016

How was it be received?### The Enterprise Waits

The first version of .NET Core addressed “green field” scenarios, or the API surface area most developers would use to build modern day apps. What it did have included:

- True cross-platform support on Linux, MacOS, and Windows

- Plenty of deployment options, including directly to Azure

- Command line tools

- Compatibility across frameworks via .NET Standard

- A compelling web story with ASP.NET Core and MVC

- A powerful database Object-Relational Mapper (ORM) via Entity Framework Core

What was it missing? Unfortunately, a lot.

Trying to translate my project to .Net Core is being a huge pain in the bum. I just want to use an appDomain but I can't have one!

— Jamie Peacock (@JamiePed) November 15, 2016

For this reason, most of the enterprise waited. I also was leery of looking at .NET Core for anything but proof-of-concept projects and purely web-based workloads. In fact, one of my most popular open source projects, an object-oriented database named Sterling, relied on so many missing features it just wasn’t feasible to try to port.

Wondering when @jeremylikness will publish his .NET core (or portable) library for Sterling. LINQ over Windows.Storage pls :-)

— Tim Heuer (@timheuer) September 21, 2011

Sterling was rooted in Microsoft’s long history of bringing .NET to multiple platforms. I originally authored it for Silverlight, based on the lack of viable “local database” options to handle scenarios like caching and querying data without round-tripping to the server. When Windows Phone was released with Silverlight support, I updated the engine to handle Windows Phone and developers adopted it mainly for tombstone support. There is even a newer port that supports the Windows Store apps (“Windows Runtime”) and includes a driver for Azure Table Storage.

The core goal of Sterling was to be non-intrusive. That meant you could wire your Plain Old C# Objects (POCOs) into a Sterling database without using special attributes or deriving from a base class. Most of the code would work “as is” because to create a Sterling database, you described the types and their keys with a fluent interface rather than annotating the classes themselves. Here’s the code to define storage for a class named “CoolColor” that instructs Sterling to use the “Id” property, which is a GUID, as the key.

CreateTableDefinition<CoolColor,Guid>(c => c.Id)

Sterling was also written to abstract away the underlying persistence engine. It is incredibly extensible and allows you to write drivers for storage so that you can support just about anything, including the “in memory” driver that ships with it. This enables scenarios like local storage in phone apps, browser storage in Silverlight apps, and file storage on servers. It also allows extensions to serializing, features triggers and allows for “byte interceptors” to address scenarios like encrypting or compressing the data stream.

To do all this, however, Sterling depends on a few key libraries.

Attempting to build Sterling on the old version (.NET Standard 1.1) resulted in a huge list of errors due to lack of support, such as:

- No support for “BackgroundWorker” class, which is how the original app handles asynchronously saving lists

- No “IsAssignableFrom” in the “Type” class to inspect inheritance

- No “IsEnum” to, well, determine if something represents an enumeration

- No “GetFields” to reflect the fields that exist on a class

- No “GetProperties” to reflect the properties that exist on a class

- Missing “MemoryStream” methods to help serialize/deserialize classes

- Lack of binary serialization (Sterling interfaces to its drivers by passing them a byte array of serialized entities)

In short, it just wasn’t ready. But that was about to change.

.NET Core 2.0 — Fire When Ready

Although .NET Core supported green field scenarios, in my experience as a consultant, the majority of enterprise customers want to migrate their existing code. Many framework and library authors also strive to make their contributions available on as many platforms as possible, but just kept hitting the wall due to the lack of API support. This all changed with .NET Core 2.0.

With support from and for .NET Standard 2.0, the API surface area increased from 13,000 to 32,000. Key scenarios were addressed, spanning serialization (most developers are probably excited about the support for binary and XML-based scenarios), threading, sockets, reflection, Linq, and more. So much has been added that I decided to dust off the old Sterling code and give porting it a whirl. Just about one hour later, I tweeted this in response to Tim’s question:

How about today? https://t.co/p8gXUg7Dw8

— Jeremy Likness ⚡️ (@jeremylikness) August 22, 2017

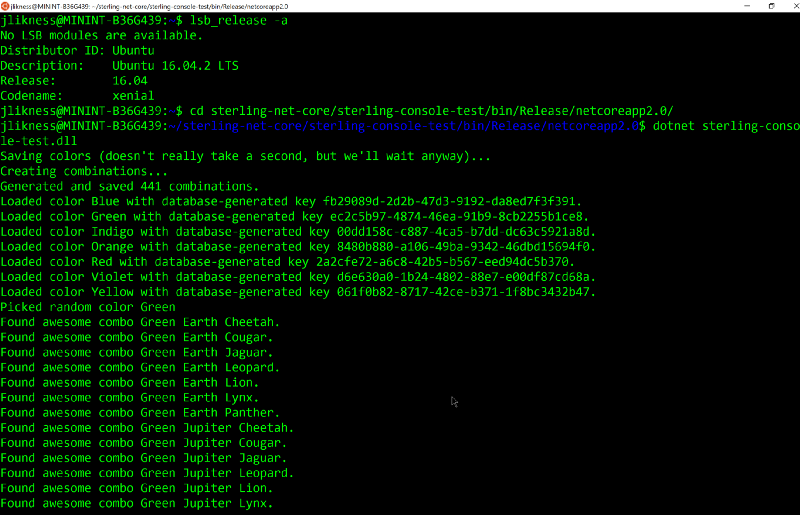

Visit the sterling-net-core repository to pull down a version of Sterling you can work with on Windows, Linux, or MacOS and run the test application. It ships with an in-memory driver and you can always write your own (I do accept pull-requests, in case anyone wants to tackle converting the asynchronous saves from BackgroundWorker to Task). Here’s a quick look at some of the scenarios that .NET Core 2.0 supported with no issues and remain unchanged from the original code.

Binary serialization of decimals

_serializers.Add(typeof (decimal),

new Tuple<Action<BinaryWriter, object>, Func<BinaryReader, object>>(

(bw, obj) =>

{

var bits = decimal.GetBits((decimal) obj);

bw.Write(bits[0]);

bw.Write(bits[1]);

bw.Write(bits[2]);

bw.Write(bits[3]);

},

br =>

{

var bits = new int[4];

bits[0] = br.ReadInt32();

bits[1] = br.ReadInt32();

bits[2] = br.ReadInt32();

bits[3] = br.ReadInt32();

return new decimal(bits);

})

);Dynamically setting a property or field using reflection

public Action<object, object> Setter

{

get

{

if (_propertyInfo != null)

{

return (obj, prop) => _propertyInfo.GetSetMethod().Invoke(obj, new[] { prop });

}

return (obj, prop) => _fieldInfo.SetValue(obj, prop);

}

}Using reflection to parse the attributes (properties, fields) of a type

var isList = typeof(IList).IsAssignableFrom(type);

var isDictionary = typeof(IDictionary).IsAssignableFrom(type);

var isArray = typeof(Array).IsAssignableFrom(type);

var noDerived = isList || isDictionary || isArray;

// first fields

var fields = from f in type.GetFields()

where

!f.IsStatic &&

!f.IsLiteral &&

!f.IsIgnored(_database.IgnoreAttribute) && !f.FieldType.IsIgnored(_database.IgnoreAttribute)

select new PropertyOrField(f);

var properties = from p in type.GetProperties()

where

((noDerived && p.DeclaringType.Equals(type) || !noDerived)) &&

p.CanRead && p.CanWrite &&

p.GetGetMethod() != null && p.GetSetMethod() != null

&& !p.IsIgnored(_database.IgnoreAttribute) && !p.PropertyType.IsIgnored(_database.IgnoreAttribute)

select new PropertyOrField(p);The Test Application

The test application defines three objects, each with their own type of unique identifier:

public class Cat

{

public string Key { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}A “combination class” references all three. Sterling is smart enough to detect when nested classes exist as part of the database, and will only serialize the key field for the nested instance rather than the full instance itself (in this way, the class is serialized with “foreign keys” instead of nested classes).

public class Combo

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public CoolColor Color { get; set; }

public Planet Planet { get; set; }

public Cat Cat { get; set; }

}The database definition returns a list of types to serialize along with their unique keys:

protected override List<ITableDefinition> RegisterTables()

{

return new List<ITableDefinition>

{

CreateTableDefinition<Cat,string>(c => c.Key),

CreateTableDefinition<CoolColor,Guid>(c => c.Id),

CreateTableDefinition<Planet,int>(p => p.Id),

CreateTableDefinition<Combo,int>(co => co.Id)

};

}Then it creates arrays with different colors, planets, and cats and generates a list with every possible combination.

public static void PopulateDatabase(ISterlingDatabaseInstance db)

{

var colors = new [] { "Red", "Orange", "Yellow", "Blue", "Green", "Indigo", "Violet"};

var cats = new [] { "Panther", "Cougar", "Lynx", "Jaguar", "Leopard", "Cheetah", "Lion"};

var planets = new [] { "Mercury", "Venus", "Earth", "Mars", "Jupiter", "Saturn", "Uranus", "Neptune", "Pluto"};

var colorItemList = colors.Select(c => new CoolColor { Name = c }).ToList();

Console.WriteLine("Saving colors (doesn't really take a second, but we'll wait anyway)...");

db.SaveAsync<CoolColor>(colorItemList); // returns a background worker if we want it

Thread.Sleep(1000); // just pause a bit because we're not monitoring the background worker

Console.WriteLine("Creating combinations...");

var planetId = 1;

var comboCount = 0;

foreach(var colorItem in colorItemList)

{

foreach(var cat in cats)

{

var catItem = new Cat { Key = $"CAT-{cat}", Name = cat };

db.Save(catItem);

foreach(var planet in planets)

{

comboCount++;

var planetItem = new Planet { Id = planetId++, Name = planet };

db.Save(planetItem);

var comboItem = new Combo { Id = comboCount, Cat = catItem, Planet = planetItem, Color = colorItem };

db.Save(comboItem);

}

}

}

Console.WriteLine($"Generated and saved {comboCount} combinations.");

}The main console app pulls and shows the list of colors, then queries for all combinations that contain a random color and outputs them to the console. The query returns a list of special “lazy loadable” items that aren’t deserialized until accessed. This was designed for scenarios that involve searching extremely long lists to find small subsets of values and avoids the cost of loading entities that aren’t needed. If there are properties you may query often, you can define custom indexes that enable you to filter to a set of keys without deserializing the full entities.

var combos = db.Query<Combo, int>()

.Where(c => c.LazyValue.Value.Color.Id == colorList[idx].Id) // filter

.Select(c => c.LazyValue.Value); // project to lazy-loaded value

var comboList = combos.Select(c => $"{c.Color.Name} {c.Planet.Name} {c.Cat.Name}");

foreach(var combo in comboList.OrderBy(c => c))

{

Console.WriteLine($"Found awesome combo {combo}.");

}… and that, my friend, is history.

On June 29th, 2010 I made my initial check-in.

Initial Sterling check-in · JeremyLikness/SterlingNoSQL@bbdd05c

On August 22nd, 2017, thanks to .NET Core 2.0, I was able to write a port that enables it to run everywhere, including Linux, MacOS and Windows!

It’s Time to Take a Serious Look

My motivation for porting Sterling was to get an idea of how far the API surface area has come in .NET Standard 2.0 by using a “real world” application. The port took less than an hour and most of that was from me updating namespaces and porting a resource file to a static class. Outside of those changes, compiling it “just worked” and I was amazed to see the test application up and running in minutes, even using a custom trigger to generate unique GUIDs for the color class.

If you were reluctant in the past to consider .NET Core due to the potential pain of migration, it’s time to reconsider and take a serious look. It has come far and .NET Standard 2.0 provides thousands of new APIs. You and fellow .NET developers can truly leverage their existing C# skills to build and deploy cross-platform apps that will run on Windows, in containers, or even on Azure as Linux apps.

Do you have a .NET Core success story? Please share it by leaving a comment. Are you still encountering pain points? Share them because the .NET Core team is dedicated to making this product great and wants to hear about the scenarios you need addressed so that you can be successful.

Related articles:

- Azure Cosmos DB With EF Core on Blazor Server (Azure)

- Blazor State Management (.NET)

- Deep Data Dive with Kusto for Azure Data Explorer and Log Analytics (Azure)

- Inspect and Mutate IQueryable Expression Trees (.NET Core)

- Look Behind the IQueryable Curtain (.NET Core)

- What is a Cloud Developer Advocate? (Microsoft)