Celebrating Twenty Years of Open Source

Jeremy Likness shares his experiences with open source code over two decades.

The recent announcement about CodePlex shutting down spurred me to migrate a few old projects and led to reflection about my past contributions to open source.

The concept of open source has been around for decades. I wrote my first line of code in 1981 and it was only a few years later that the GNU Project was launched with the vision of free software and massive collaboration. Before the Internet became ubiquitous, we would share code through local gatherings called “swap meets.”

Imagine convention halls filled with tables and power cords so computer enthusiasts (I think we were called “geeks”) could drag their twenty-pound towers and fifty-pound monitors around and copy disks from each other. OK, let’s be honest. There may have been a little bit of pirating going on at those meets, too.

Much activity in those days was focused on breaking or “cracking” increasingly sophisticated anti-copy security measures in commercial software. When successful, developers would leave their calling card by programming “intros” with personal brands and “shout-outs.” Many “crews” of developers created longer running “demos” to show off their coding ability. When I was 14 I labored with a good friend through one summer to create a humbly named “8th wonder of the world.”

The capture doesn’t do it justice as much of the flicker is non-existent on a “real” breadbox (what we called the Commodore 64), but I was hardly keeping pace with groups like Crest who were able to write code that tricked the hardware into producing higher resolution graphics than it was supposed to support and could create images with 64k colors on an 8-bit machine that only had a palette of 16.

In those days we shared our creations by swapping disks or going through the painfully long process of uploading and downloading to and from bulletin board systems (BBS).

Open Source Quake

As software evolved through phases like “Shareware” and launched successful franchises like Doom, I continued to stay passionate about programming. After Quake was released, I had a very unique opportunity to dabble in gaming. I had previously avoided it due to a severe weakness with vector math and ray tracing equations, but Quake provided it’s own language and allowed me to focus on game logic rather than worry about trivial effects like 3D graphics and gravity.

I had some initial success with a modification I wrote under the nickname “Nikodemos” called Midnight Capture the Flag. An eager gamer shared the idea with me in a chat room but lacked the programming chops to pull it off, so I rolled up my sleeves and got to work. The concept was great because most modifications required downloading assets over extremely slow connections.

MidCTF was a “server modification” so it could be played without any downloads by the player. It took advantage of the revolutionary 3D audio Quake provided, and used an algorithm to scan levels, turn off all the lights, and equip the player with a flashlight.

Before GitHub and CodePlex we had well known public FTP sites to upload code to, so I started uploading code and posting about it on various news sites. The MidCTF mod went viral (yep, we even had viral those days) and brought me to the attention of a group that was writing a TC (short for “total conversion”) of Quake.

This game, called SWAT Quake, had completely custom gameplay.

I had to write from scratch features that are now commonplace. For example, there were limited team sizes so I had to queue players who connected but couldn’t play yet. To make their lives interesting, I figured out how to anchor “cameras” in levels, use algorithms to determine which cameras had the highest density of players within sight and auto-switch to view the action.

Another fun modification was “climbing gloves.” A fugitive trying to escape security could use these to climb walls. To make this work, I wrote an action to “engage” the claws. While engaged, I shot a vector from the player forward and determined whether they were in contact with a “wall.” If they were, I applied an acceleration to the player that was slightly higher than the reverse of gravity so they would “climb.”

It was a surprisingly realistic effect, because an opponent could shoot a rocket and miss, but the explosion would knock the player away from the wall and cause them to fall quite convincingly. I consider those initial Quake modifications my first “open source” projects that were posted on public servers. But what about business-focused open source?

The Real Job

After SWAT was released, I did the unthinkable: I started dating my soon-to-be wife, and I got a “real job.” This left me little time to focus on my gaming pursuits. At the time, open source was considered by most corporations to be completely incompatible with enterprise apps. I believe there were three driving factors that slowed adoption:

- Share and share-alike … no one wanted to have to share their proprietary “secret sauce” code, and the perception was most libraries required this to be used.

- The perception that open source projects were in perpetual beta, never quite finished, not as polished as professional code and would be a nightmare to support.

- Security concerns.

All three are very valid reasons and haven’t gone away. What has changed however is the momentum with which projects have been adopted and accepted as a part of the enterprise. That would come much later, however. At the start of my professional career, movies like AntiTrust reflected the general sentiments at the time: corporations were greedy, code-mongering organizations who refused to give an inch back to the community, while open source developers worked out of garages with zero income.

For a decade, open source wasn’t even on my radar. Fast forward …

Sterling

On June 28th, 2010 I “checked in” the code to my first open source project to CodePlex. You can view the migrated commit on GitHub here. Like most popular projects, this wasn’t a case of building something I hoped people would use, but rather addressing a need I knew developers had. Sterling was and probably will always be my largest open source effort.

In general, a common complaint about Silverlight was that it had no local database. Although best practices at the time embraced an N-tier architecture that relied on web services to shuttle data to and from the browser, it was difficult to cache assets locally. Fortunately, Silverlight had the concept of “isolated storage” and just needed some help making it easier to store and retrieve data.

At the time I had been experimenting with reflection to dynamically create entities from JSON, and realized that it was not difficult to walk the properties of an object and use a binary writer to serialize them. Classes are just bags of properties, some of which are classes themselves. Sterling would allow you to define a database, register classes, and use lambda expressions to describe keys and indexes.

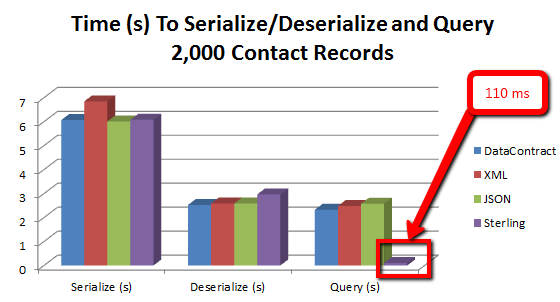

The first iteration of Sterling came fairly quickly, but it was the optimizations that made it unique. I quickly deduced that it would be faster to store properties and fields in a cache rather than use reflection each pass. The algorithms to handle arrays and dictionaries were long and unwieldy until I had a flash of insight that enabled me to refactor about 1000 lines of code that handled only a few cases to 300 lines that handled almost every case.

The introduction of Windows Phone 7 led to a major surge of interest in Sterling. I rewrote the engine to decouple storage from the database logic, so I could use a common “core” then write adapters for the phone vs. Silverlight. This made it easy to write a server-side .NET version for caching as well. I introduced triggers, decoupled logging, provided a way for custom serialization schemes to handle complex types or just make “short cuts” if their serialization was already handled, and allowed “byte interceptors” that could manipulate the stream for compression and/or encryption.

Embracing Open Source

There was no doubt in my mind that Sterling would be open source. This not only enabled adoption and helped solve a real problem developers were having, but also enabled contributions from the community. I had several collaborators do everything from push bug fixes to write new adapters and even port the code over to the Windows Runtime when it came out.

Ultimately, Sterling did well for preserving state and querying small collections but it fell apart with extremely large datasets. Eventually solutions like SQLite were ported over and helped fill the demand. I had one fleeting offer from a major tools vendor to purchase Sterling that fell apart when the technology officer left for another company.

Jounce

On October 4, 2010 I committed the initial build for Jounce, a framework for building Silverlight business applications.

Again, Jounce was not an attempt to create something people would adopt, but a reaction to a problem that needed solving. After delivering dozens of Silverlight presentations, two things became evident to me: first, a lot of developers were building the applications the wrong way. They weren’t taking advantage of built-in features and were locking in code that would make it extremely difficult to migrate and support later on.

Second, although several frameworks like Prism existed, they were overly complicated to most developers and difficult to adopt. Developers were creating dependencies on a framework and then only using 10% of it.

I recognized the several successful Silverlight production projects I wrote, including a social media analytics tool I developed for Microsoft and a pilot slate application for Rooms To Go, had several patterns in common. They leveraged the Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) pattern, used some simple command and messaging patterns, and relied on the Managed Extensibility Framework (MEF) for dependency resolution and dynamic model loading.

I encapsulated these features into Jounce, uploaded it to CodePlex, and created a video to show how easy it was to get started:

Jounce was specifically designed for Silverlight and did not survive Silverlight’s demise just a year later. Some other powerful frameworks designed during that period, however, still live on, like MVVM Light.

Modern Times

The version control systems I used in the past centered around TFSVC. (With one exception: I did install an instance of Darcs at one company and use it for awhile). Git was a mystery to me. Some associates of mine insisted it was the future and that I should get to know it.

In January of 2014 I made my first commit to GitHub with jsEventAgg, a simple pub/sub platform for JavaScript. To really get to learn and understand git, I leveraged it for a talk at a code camp that featured an Angular Health App. I created the application and committed after each major step, then pulled the commits to show each stage of development.

The Angular Health App was a valuable project because I later created a version with Angular 2, a version that uses Redux, and a version written with Babel.js to compare and contrast the different development options.

This was the start of me moving entirely over to GitHub and all of my open source projects have been hosted there since.

The majority of open source projects I publish are proof-of-concepts, demos, and tutorials. There are a few exceptions. For example, jlikness.watch made it possible to see just how bad dirty checking could get in Angular 1.x apps, and qorlate made it easier to coordinate promises and even deal with them like streams (a la RxJs). jsInject is a functional JavaScript dependency-injection module designed to teach how Angular 1.x dependency injection worked, and my most recent module provides service location for microservices as a micro-locator.

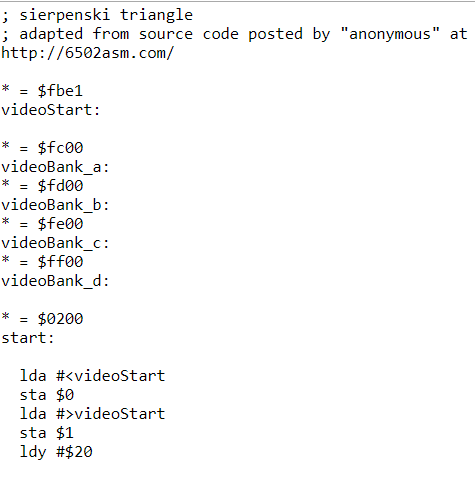

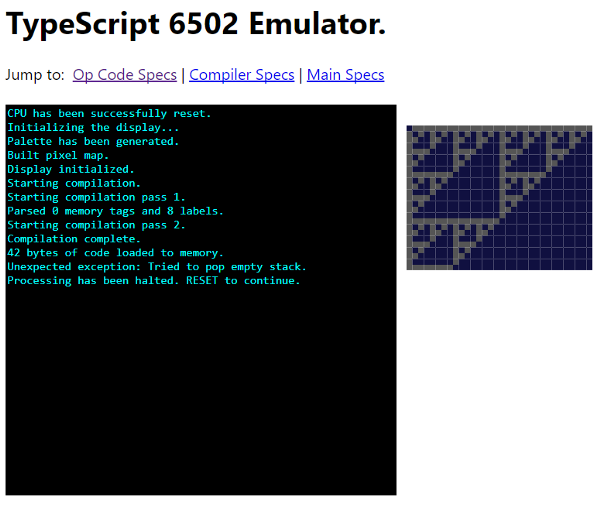

I also did some very involved projects that reflect my nostalgia for 8-bit software. A major example of this is the T6502 emulator, a full emulator of the 6502 CPU. It provides a compiler, has a debug feature, and even connects memory to a canvas element to provide graphics capability. Here’s an instance of the running emulator.

For code snippets, I share JavaScript solutions via jsFiddle.net.

Containers

Perhaps the most amazing evolution of open source to me has been the introduction of containers. Although not necessarily tied to source, they facilitate open source development in ways that were never possible before.

For example, if you work on Angular apps you’ve probably been hit with the migration of the Angular Command Line Interface (CLI) to a new package name. If you’ve installed the latest version and have projects made with the old tool, they won’t work … that is, unless you leverage a solution like this ng2build container. It allows you to mount a path and run the older version of the CLI inside of a container.

As of this writing there are thousands of available containers, and popular ones have been pulled millions of times by developers. Of course, the technology that makes this possible ( Docker) is, well, open source.

Just five years ago I had to ask special permission to use open source tools in enterprise projects. I thought that Microsoft might revoke my MVP status because the technologies I evangelized the most were open source. Today, it is fairly common to see open source in almost every project. Microsoft has it’s own open source, cross-platform IDE in Visual Studio Code, collectively through its employees makes the most open source contributions on GitHub and even has a website dedicated to “the open source discussion.”

20 Years

Although several decades have gone by, one passion of mine has remained consistent. Software development transformed my life and my personal mission continues to be to empower developers to be their best. There has always been a platform for sharing code, best practices, and mentoring developers on new projects, but open source is the catalyst that not only transforms the lives of developers but boosts start-ups and injects new enthusiasm into large corporations that are learning the true meaning of “agile.”

One last bit of advice. I have done very well in my professional programming career, and open source always served to move it forward. There is a myth that “giving away” code somehow may diminish your value, but I disagree. Keep in mind there will always be proprietary algorithms and solutions that are a company’s “secret sauce” and I do not believe all code should be in the public domain. However, embracing open source and sharing common tools and libraries or even custom games gave me unique experiences and enabled me to be a part of programming history that I otherwise would not have had access to. I got to be an active participant in the longest interview.

One door closes, and other doors open. If you are not participating in an open source project or sharing your knowledge with the world, why not start today? You never know just who you might impact or how your contributions may transform technology as we know it. After all, most of the disruptive technologies we know of today (Netflix, Uber, PayPal, etc.) are largely composed of and on open source frameworks, libraries, platforms, and tools.

Related articles:

- Deploy WebAssembly from GitHub to Azure Storage Static Websites with Azure Pipelines (Github)

- From Angular to Blazor: The Health App (Angular)

- The Year of .NET Core, Angular, and Web API Design: 2018 in Review (Angular)

- TypeScript for JavaScript Developers by Refactoring Part 1 of 2 (Typescript)

- TypeScript for JavaScript Developers by Refactoring Part 2 of 2 (Typescript)

- Vanilla.js — Getting Started (Angular)