30 Years of “Hello, World”

This article explores what “Hello, World” looks like in several different languages over the course of 30 years.

I recently took a vacation the same week as the 4th of July and had lots of time to reflect upon my career to date. It was a little shocking to realize I’ve been writing code for nearly 30 years now! I decided to take advantage of some of the extra time off to author this nostalgic post and explore all of the languages I’ve worked with for the past 30 years. So this is my tribute to 30 years of learning new languages starting with “Hello, World.”

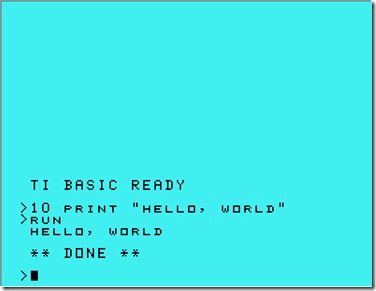

The first programming language I learned was TI BASIC, a special flavor of BASIC written specifically for the TI 99/4A microcomputer by Microsoft. BASIC, which stands for Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code, was the perfect language for a 7-year old to learn while stuck at home with no games. The language organized lines of codes with line numbers and to display something on the screen you “printed it” like this:

1981 — TI BASIC

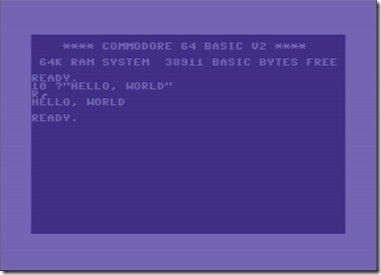

I spent several months writing “choose your own adventure” games using this flavor of BASIC, and even more time listening to the whistles, crackles, and hisses of a black tape cassette recorder used to save and restore data. Probably the most exciting and pivotal moment of my young life was a few years later when my parents brought home a Commodore 64. This machine provided Commodore BASIC, or PET BASIC, right out of the box. This, too, was written by Microsoft based on the 6502 Microsoft BASIC written specifically for that line of chips that also happened to service Apple machines at the time.

1984 — Commodore BASIC

The question mark was shorthand for the PRINT command, and the weird characters afterwards were the abbreviated way to type the RUN command (R SHIFT+U — on the Commodore 64 keyboard the SHIFT characters provided cool little graphics snippets you could use to make rudimentary pictures).

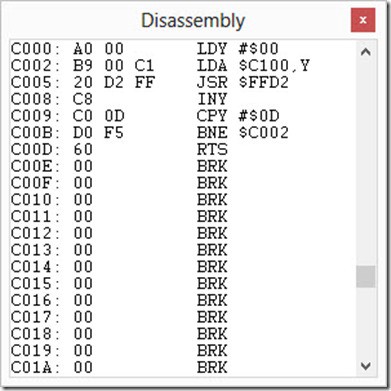

I quickly discovered that BASIC didn’t do all of the things I wanted it to. The “demo scene” was thriving at the time and crews were making amazing programs that would defy the limits of the machine. They would do things like trick the video chip into drawing graphics that shouldn’t be possible or scroll content or even move data into the “off-limits” border section of the screen. Achieving these feats required exact timing that was only possible through the use of direct machine language code. So, I fired up my machine monitor (the name for the software that would allow you to type machine codes directly into memory) and wrote this little program:

1985 – 6502 Machine Code

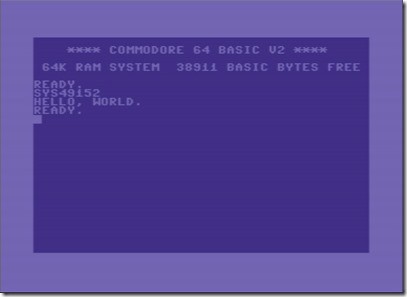

This little app loaded the “Y-accumulator” with an index, then spun through memory starting at $C100, sending the characters one at a time to a ROM subroutine that would print them to the display. This is the equivalent of a for loop (for y = 0; y <= 0x0d, y++) in machine code. The RTS returns from the subroutine. In order to execute the program, you had to use the built-in SYS command that would call out to the memory address (unfortunately, you had to convert from hexadecimal $C000 to decimal 49152, but otherwise it worked like a charm). I had the PETSCII characters for “HELLO, WORLD” stored at memory address $C100 (yes, the Commodore 64 had it’s own special character page). Here is the result:

Of course life got a little easier when I moved from raw machine code to assembly. With assembly, I could pre-plan my software, and use labels to mark areas of memory without having to memorize memory addresses. The exact same program shown above could be written like this:

1986 – 6502 Assembly

* = $C000 ;set the initial memory address

CHROUT = $FFD2 ;set the address for the character out subroutine

LDY #$00 LOOP

LDA HELLO, Y

CMP #$00

BEQ END

JSR CHROUT

INY

BNE LOOP

END RTS

HELLO ASC 'HELLO, WORLD.' ; PETSCII

HELLOEND DFB 0 ; zero byte to mark the end of the stringAbout that time I realized I really loved writing software. I took some courses in high school, but all they taught was a silly little Pascal language designed to make it “easy” to learn how to program. Really? Easy? After hand-coding complex programs using a machine monitor, Pascal felt like a lot of overkill. I do have to admit the syntax for “Hello, World” is straightforward.

1989 — Pascal

program HelloWorld;

begin

writeln('Hello, World.');

endI thought the cool kids at the time were working with C. This was a fairly flexible language and felt more like a set of functional macros over assembly than an entirely new language. I taught myself C on the side, but used it only for a short while.

1990 — C

#include <stdio.h>

main()

{

printf("Hello World");

}The little program includes a library that handles Standard Input/Output and then sends the text on its way. Libraries were how C allowed us to develop cross-platform — the function was called the same thing whether you were on Windows or Linux, but the library itself implemented all of the low-level routines needed to make it work on the target machine. The above code was something I would tinker with on my Linux machine a few years later. It’s hard to describe if you weren’t into computers during this time, but it felt like you weren’t a true programmer unless you built your own custom Linux installation. By “built your own” I mean literally walked through the source and customized it to match the specific set of hardware you owned. The most fun was dealing with video cards and learning about “dot clocks” and all of the nuances of making the motherboard play nicely with the graphics chip. Anyway, I diverge.

C was not really a challenge for me to learn, but I quickly figured out the cool kids were doing something different and following this paradigm known as “object-oriented programming.” Machine code and assembly are probably the farthest you can get from OO, so the shift from procedural to object-oriented was a challenge I was ready to tackle. At the time you couldn’t simply search online for content (you could, but it was using different mechanisms with far fewer hits) so I went out and bought myself a stack of C++ books. It turns out C++ supports the idea of “objects.” It even used objects to represent streams and pipes to manipulate them. This object-oriented stuff also introduced the idea of namespaces to better manage partitions of code. All said, “Hello, World” becomes:

1992 — C++

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

cout << "Hello World";

return 0;

}I headed off to college and was disappointed that the place I went did not have courses that covered the “modern” languages I was interested in like C and C++. Instead, I had to muddle through a course where homework was performed on the mainframe we called “Cypher” using an interesting language called Fortran that actually cares about what column you put your code in! That’s right, the flavor of the language at the time designated column 1 for comments, columns 1–5 for statement labels, column 6 to mark a continuation, and only at column 7 could you begin to write real code. I learned enough of Fortran to know I never wanted to use it.

1993 — Fortran

PROGRAM HELLOWORLD

PRINT *, 'Hello, World!'

ENDBecause I wasn’t much into the main courses I spent most of the evenings down in the computer lab logging onto the massive Unix machines the college had. There I discovered the Internet and learned about the “old school” way of installing software: you pull down the source, build it, inspect the errors, tweak it, fix it, and get a working client. Honestly, I don’t know how you could use Unix without learning how to program based on the way things ran back then so I was constantly hacking and exploring and learning my way around the system. One fairly common thing to do would be execute commands that would dump out enormous wads of information that you then had to parse through using “handy” command line tools. One of the coolest languages I learned during that time was PERL. It doesn’t do the language justice to treat it with such a simple example, but here goes:

1993 — PERL

$welcome = "Hello World";

print "$welcome\n";At the same time I quickly discovered the massive World Wide Web (yes, that’s what we called it back then … the Internet was what all of those fun programs like Gopher and Archie ran on, and the World Wide Web was just a set of documents that sat on it). HTML was yet another leap for me because it was the first time I encountered creating a declarative UI. Instead of loading up variables or literals and calling some keyword or subroutine, I could literally just organize the content on the page. You’d be surprised that 20 years later, the basic syntax of an HTML page hasn’t really changed at all.

1993 — HTML

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello, World</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, World</h1>

</body>

</html>This was an interesting time for me. I had moved from my personal computers (TI-99/4A and Commodore 64 with a brief period spent on the Amiga) to mainframes, and suddenly my PC was really just a terminal for me to connect to Unix mainframes. I also ran a Linux OS on my PC because that was the fastest way to connect to the Internet and network at the time — the TCP/IP stack was built-in to the OS rather than having to sit on top like it did in the old Windows versions (remember NETCOM anyone?) . Most of my work was on mainframes.

I did realize that I was losing touch with the PC world. At that time it was fairly obvious that the wild days of personal computing were over and the dust had settled around two machines: the PC, running Windows, for most of us, and the Mac for designers. That’s really what I believed. I had a roommate at the the time who was all over the Mac and at the time he designed coupons. He had all of these neat graphics design programs and would often pull out Quark and ask me, “What do you have on the PC that could do this?” I would shrug and remind him that I can’t even draw a circle or square so what on earth would I do with that graphics software? I liked my PC, because I understood software and I understood math so even if I couldn’t draw I could certainly use math to create fractal graphics or particle storms. Of course, doing this required having a graphics card and wasn’t really practical from a TELNET session to a Unix box, so I began learning how to code on the PC. At the time, it was Win32 and C++ that did the trick. You can still create boilerplate for the stack in Visual Studio 2012 today. I won’t bore you with the details of the original “HELLO.C” for Win32 that spanned 150 lines of code.

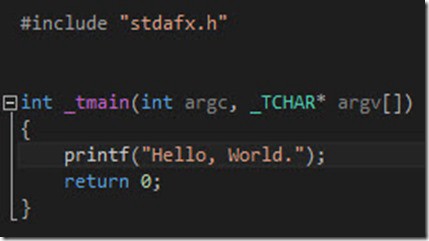

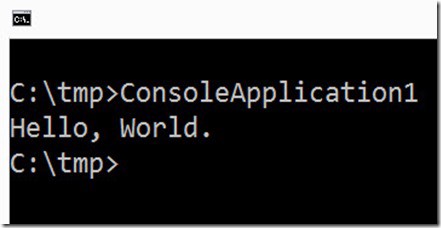

1994 — Win32 / C++ (Example is a bit more recent)

Dropping to the command line and executing this gives us:

My particle streams and Mandelbrot sets weren’t doing anything for employment, however, so I had to take a different approach. Ironically, my professional start didn’t have anything to do with computers at all. I started working for an insurance company taking claims over the phone in Spanish. That’s right. In the interview for a lower wage job that I was “settling for” to pay the bills while I stayed up nights and hacked on my PC I happened to mention I spoke Spanish. They brought in their bilingual representative to interview me and I passed the test, and within a week I was in a higher paid position learning more Spanish in a few short calls than I had in all my years in high school.

I was young and competitive and we were ranked based on how many claims we successfully closed in a day. I was not about to fall behind just because the software I was using tended to crash every once in awhile. It was a completely new system to me — the AS/400 (now called the iSeries) — but I figured it out anyway and learned how to at least restart the claims software after a crash. The IT department quickly caught on and pulled me aside. I was afraid I was in trouble, but instead they extended me an offer to move into IT. I started doing third shift operations which meant basically maintaining the AS/400 systems and swapping print cartridges on the massive printers that would print out policy forms and claims.

When I went to operations the process for swapping printing cartridges took most of the shift. This is because certain forms were black ink only, but other forms had green or red highlights. The printers could only handle one ink profile so whenever a different type of form was encountered, we’d get an alert and go swap everything out. I decided this was ridiculous so I took the time to teach myself RPG. I wrote a program that would match print jobs to the ink color and then sort the print queue so all black came together, all green, etc. This turned an 8 hour job into about a 2 hour one and gave me lots of time to study RPG. The original versions — RPG II and RPG III — were crude languages originally designed to simply mimic punch card systems and generate reports (the name stands for Report Generator). Like Fortran, RPG was a positional language.

1995 — RPG

I 'HELLO, WORLD' C HELO

C HELO DSPLY

C SETON LRNote the different types of lines indicated by the first character (actually it would have been several columns over but I purposefully omitted some of the margin code). This defines a constant, displays it, then sets an indicator to cause the program to finish.

After working in operations I landed a second gig. The month-end accounting required quite a bit of time and effort. The original system was a Honeywell mainframe that read punch cards. A COBOL program was written that read in a file that emulated a punch card and output another file that was then pumped into the AS/400 and processed. After this, the various accounting figures had to match. Due to rounding errors, unsupported transactions, and any other number of issues the figures almost never matched so the job was to investigate the process and find out where it broke, then update the code to fix it. We also had an “emergency switch” for the 11th hour that would read in the output data and generate accounting adjustments to balance the books if we were unable to find the issues. Although I didn’t do a lot of COBOL coding, I had to understand it well enough to read the Honeywell source to troubleshoot issues on the AS/400 side.

1995 — COBOL

IDENTIFICATION DIVISION.

PROGRAM-ID. HELLO.

ENVIRONMENT DIVISION.

DATA DIVISION.

WORKING-STORAGE SECTION.

01 WELCOME-MESSAGE PIC X(12).

PROCEDURE DIVISION.

PROGRAM-BEGIN.

MOVE "Hello World" TO WELCOME-MESSAGE.

DISPLAY WELCOME-MESSAGE.

PROGRAM-DONE.

STOP RUN.It was only a short time later that the top RPG guru came to our company to give us a three day class because the coolest thing was happening in the AS/400 world. Not only were the AS/400 machines moving to 64-bit (and everyone knows that double bits is twice as nice, right?) but the RPG language was getting a facelift and with version IV would embrace more procedural and almost object-oriented principles than ever before. How cool was that? We jumped into training and I laughed because all of the old RPG developers were scratching their heads trying to muddle through this “new style of programming” while I was relieved I could finally get back to the more familiar procedural style I was used to with C and C++ rather than the tight, constricted, indicator and column-based language RPG had been.

Some developers may get a kick out of one of the ‘”features” that really knocked the socks off everyone. The language required the instructions to begin at a certain column, and inputs into the instructions would precede them. This was a very limited space so you could really only load constants of a few characters, otherwise you had to specify them as constants or data structures and read them in. The new language moved the keyword column to the right so there was more room for the “factor one” position. That meant we could now do “Hello, world” in just a few lines. The language was also more “procedural” so you could end a program by returning instead of setting on the indicator (although if I remember correctly, a return on the main program really just set that indicator under the covers).

1996 — RPG/ILE

C "HELLO, WORLD"; DSPLY

C RETURNThe AS/400 featured a database built into the operating system called DB2. For the longest time the database only supported direct interaction via RPG or other software and did not support the SQL syntax. It was rolled out as a special package called SQL/400 but the underlying support was there. I wrote one of my first published (print) articles about tapping into SQL for the AS/400 in 1998 (Create an Interactive SQL Utility). There are probably a million ways to do “Hello, World” in SQL but perhaps the easiest is this:

1998 — SQL

SELECT 'HELLO, WORLD' AS HELLOI apologize for stepping out of chronological order but the SQL seemed to make sense as part of my “main” or “paid” job. At the same time I had been doing a lot of heavy gaming, starting with DOOM (the first game I was so impressed with, I actually sent in the money to purchase the full version), continuing with DOOM II and HEXEN and culminating in Quake. If you’re no familiar with the history of first-person shooters, Quake was the game that changed the history of gaming. It offered one of the first “true” 3D worlds (the predecessors would simulate 3D with 2D maps that allowed for varying floor and ceiling heights) and revolutionized the death match by supporting TCP/IP and using advanced code that allowed for more gamers in the same map than ever before.

It also was extremely customizable. Although I am aesthetically challenged and never caught on to creating my own models or maps, I jumped right into programming. Quake offered a C-based language called QuakeC that you would literally compile into a special cross-platform byte code that could run on all of the target platforms that Quake did. I quickly wrote a number of modifications to do things like allow players to catch fire or cause spikes to ricochet realistically from walls. Someone in a chat room asked me to program an idea that I became famous for which was called “MidnightCTF” and essentially took any existing map and turned off all of the lights but equipped the players with their own flashlight. Quake was one of the first games to support true 3D sound so this added an interesting dimension to game play.

Someone even included a code snippet from one of my modifications in the “Dictionary of Programming Languages” under the QuakeC entry. Nikodemos was the nickname I used when I played Quake. The “Hello, World” for QuakeC is really just a broadcast message that gets sent to all players currently in the game.

1996 — QuakeC

bprint("Hello World\n");By this time I realized the Internet was really taking off. I had been frustrated in 1993 when I discovered it at college and no one really knew what I was talking about, but just a few years later everyone was scrambling to get access (a few companies like AOL and Microsoft with MSN actually thought they could build their own version … both ended up giving in and plugging into THE Internet). I realized that my work on mainframes was going to become obsolete or at best I’d be that developer hidden in the back corner hacking on “the old system.” I wanted to get into the new stuff.

I transferred to a department that was working on the new stuff — an application that was designed to provide visibility across suppliers by connecting several different systems in an application written with VB6 (COM+) and ASP.

1998 — VB6 (COM) w/ ASP

Public Class HelloWorld

Shared Public Function GetText() As String

return "Hello World"

End Function

End Class

<%@ Page Language="VB" %>

<OBJECT RUNAT=SERVER SCOPE=Session ID=MyGreeting PROGID="MyLibrary.HelloWorld"></OBJECT>

<HTML><HEAD><TITLE><%= MyGreeting.GetText() %></TITLE></HEAD>

<BODY><H1><%= MyGreeting.GetText() %></H1></BODY>

</HTML>At the time I had the opportunity to work with a gifted architect who engineered a system that at the time was pretty amazing. Our COM+ components all accepted a single string parameter in the interface because incoming information was passed as XML. This enabled us to have components that could just as easily work with messages from the web site as they could incoming data from a third-party system. It was a true “web service” before I really understood what the term meant. On the client, forms were parsed by JavaScript and packaged into XML and posted down so a “post” from the web page was no different than a post directly from the service. The services would return data as XML as well. This would be combined with a template for the UI (called PXML for presentation XML) and then an XSLT template would transform it for display. This enabled us to tweak the UI without changing the underlying code and was almost like an inefficient XAML engine. This was before the .NET days.

JavaScript of course was our nemesis because we had to tackle how to handle the various browsers at the time. Yes, the same problems existed 15 years ago that exist today when it comes to JavaScript and cross-browser compatibility. Fortunately, all browsers agree on the way to send a dialog to the end user.

1998 — JavaScript

alert('Hello, World.');A lot of our time was spent working with the Microsoft XML DLLs (yes, if you programmed back then you remember registering the MSXML parsers). MSXML3.DLL quickly became my best friend. Here’s an example of transforming XML to HTML using XSLT.

1998 — XML/XSLT to HTML

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<hello>Hello, World!</hello>

<?xml version='1.0'?><xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:template match="hello">

<html>

<head><title><xsl:value-of select="."/></title></head>

<body><h1><xsl:value-of select="."/></h1></body>

</html>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>Const MSXMLClass = "MSXML2.DOMDocument"

Set XSLT = Server.CreateObject(MSXMLClass)

Set XDoc = Server.CreateObject(MSXMLClass) XDoc.load(Server.MapPath("hello.xml"))

XSLT.load(Server.MapPath("hello.xsl")) Response.ClearResponse.Charset = "utf-8"

Response.Write XDoc.transformNode(XSLT)I spent several years working with that paradigm. Around that time I underwent a personal transformation and shed almost 70 pounds to drop from a 44” waist down to 32” and became very passionate about fitness. I started my own company “on the side” and eventually left the company I was at to become Director of IT for a smaller company that was providing translation services to hospitals and had a Spanish-language online diet program. Once again I was able to tap into my Spanish-speaking ability because the translations were from English to Spanish and vice versa. I learned quite a bit about the differences between various dialects and the importance of having targeted translations. I also rewrote an entire application that was using ASP with embedded SQL calls and was hard-coded to Spanish to be a completely database-driven, white-labeled (for branding) localized app (the company was looking to branch into other languages like French). It was an exciting time and while I used the Microsoft stack at my job, the cost of tools and servers led me to the open source community for my own company. That’s when I learned all about the LAMP stack … Linux OS, Apache HTTP Server, MySQL Database, and PHP for development. Ironically this experience later landed me one of my first consulting gigs working for Microsoft as they attempted to reach out to the open source community for them to embrace Silverlight … but that’s a different story.

2002 — PHP

<?php

$hello = 'Hello, World.';

echo "$hello";

?>

Several years passed working on those particular platforms when I had the opportunity to move into yet another position to build the software department for a new company. I was the third employee at a small start-up that was providing wireless hotspots before the term became popular. If you’ve ever eaten at a Panera or Chick-fil-A or grabbed a cup of coffee at a Caribou Coffee then you’ve used either the software I helped write, or a more recent version of it, to drive the hotspot experience. When I joined the company the initial platform was written on Java. This was a language I’d done quite a bit of “tinkering” with so it wasn’t a gigantic leap to combine my C++ and Microsoft stack skills to pick it up quickly.

2004 — Java

public class Hello {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, World");

}

}I’ve got nothing against Java as a language, but the particular flavor we were using involved the Microsoft JVM that was about to get shelved, and a custom server that just didn’t want to scale. I migrated the platform over to .NET and it was amazing to see a single IIS server handling more requests than several of the dedicated Java servers could. I say, “migration” but it was really building a new platform. We looked into migrating the J++ code over to C# but it just wasn’t practical. Fortunately C# is very close to Java so most of the team was able to transition easily and we simply used the existing system as the “spec” for the new system to run on Windows machines and move from MySQL to SQL Server 2005. Note how similar “Hello, World” is in C# compared to Java.

2005 — C#

public class Hello

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("Hello, World!");

}

}Part of what made our company so successful at the time was a “control panel” that allowed us to manage all of our hotspots and access points from a central location. We could reboot them remotely, apply firmware updates, and monitor them with a heart beat and store history to diagnose issues. This software quickly evolved to become a mobile device management (MDM) platform that is the flagship product for the company today. They rebranded their name and came out with the product but our challenge was providing an extremely interactive experience in HTML that was cross-browser compatible (the prior solution used Microsoft’s custom Java applets). We succeeded in building a fairly impressive system using AJAX and HTML but our team struggled with complex, rich UIs when they had to test across so many browsers and platforms. While we needed to maintain this for the hotspot login experience, the management side was more flexible so I researched some alternative solutions.

When I discovered Silverlight, I was intrigued but decided to pilot it first. I was able to stand up a POC of our monitoring dashboard in a few weeks and everyone loved it so we decided to go all-in. At my best guess our team was able to go from concept to delivery of code about 4 times faster using Silverlight compared to the JavaScript and HTML stack. This was while HTML5 was still a pipe dream. We built quite a bit of Silverlight functionality before I left. By that time we were working with Apple on the MDM side and they of course did not want Silverlight anywhere near their software, and HTML5 was slowing gaining momentum, so I know the company transitioned back, but I was able to enjoy several more years building rich line of business applications in a language that brought the power of a declarative UI through XAML to as many browsers and platforms as were willing to allow plugins (I hear those aren’t popular anymore).

2008 — Silverlight (C# and XAML)

<UserControl x:Class="SilverlightApplication1.MainPage">

<Grid x:Name="LayoutRoot" Background="White">

<TextBlock x:Name="Greeting"></TextBlock>

</Grid>

</UserControl>public partial class MainPage : UserControl

{

public MainPage()

{

InitializeComponent();

Loaded += MainPage_Loaded;

}

void MainPage_Loaded(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

Greeting.Text = "Hello, World.";

}

}Silverlight of course went down like a bad stock. It was still a really useful, viable technology, but once people realized Microsoft wasn’t placing much stock in it (pardon the pun) it was dead on arrival — had really nothing to do with whether it was the right tool at the time, and everything to do with the perception of it being obsolete. HTML5 also did a fine job of marketing itself as “write once, run everywhere” and hundreds of companies dove in head first before they realized their mistake (it’s really “write once, suck everywhere, then write it again for every target device”).

The parts we loved about Silverlight live on, however, in Windows 8.1 with the XAML and C# stack. For kicks and giggles here’s a version of “Hello, World” that does what the cool kids do and uses the Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) pattern.

2011 — WinRT / C#

<Grid Background="{StaticResource ApplicationPageBackgroundThemeBrush}">

<Grid.DataContext>

<local:ViewModel/>

</Grid.DataContext>

<TextBlock Text="{Binding Greeting}"/>

</Grid>public class ViewModel

{

public string Greeting

{ get

{

return "Hello, World";

}

}

}While Windows 8.1 has kept me occupied through my writing and side projects, it’s still something new to most companies and they want a web-based solution. That means HTML and JavaScript, so that’s what I spend most of my time working with. That’s right, once I thought I got out, they pulled me back in. After taking a serious look at what I hate about web development using HTML and JavaScript, I decided there had to be a better way. Our team got together and looked at potential ways and found a pretty cool solution. Recently a new language was released called TypeScript that is a superset of JavaScript. This doesn’t try to change the syntax and any valid JavaScript is also valid TypeScript. The language, however, provides some development-time features such as interfaces that help shape API calls and provide rich discovery (without ever appearing in the generated code) while also giving us constructs like classes with inheritance, strongly typed variables, and static modifiers that all compile to perfectly valid, cross-browser JavaScript.

Using TypeScript was an easy decision. Even though it is in beta, it produces 100% production ready JavaScript, so if we found it wouldn’t work well we knew we could yank the plug and just move forward with the JavaScript. It turns out it was incredibly useful — even a few skeptics on the team who were JavaScript purists and hated any attempt to “modify the language” agree that TypeScript gives us an additional level of control, ability to refactor, and supports parallel development and has accelerated our ability to deliver quality web-based code.

2012 — TypeScript

class Greeter {

public static greeting: string = "Hello, World";

public setGreeting(element: HTMLElement): void {

element.innerText = Greeter.greeting;

}

}

var greeter: Greeter = new Greeter();

var div: HTMLElement = document.createElement("div");

greeter.setGreeting(div);

document.body.appendChild(div);…or, as an alternative approach (because, after all, valid JavaScript is valid TypeScript):

alert('Hello, World.');TypeScript wasn’t the only change we made. We also wanted to remove some of the ritual and ceremony we had around setting up objects for data-binding. We were using Knockout which is a great framework but it also required more work than we wanted. Someone on our team investigated a few alternatives and settled on AngularJS. I was a skeptic at first but quickly realized this was really like XAML for the web. It gave us a way to keep the UI declarative while isolating our imperative logic and solved yet another problem. Our team has been happily using a stack with TypeScript and AngularJS for months now and absolutely loves it. I’m working on a module for WintellectNOW because I believe this is a big thing. However, if 30 years have taught me anything, it’s this: here today, gone tomorrow. I’m not a C# developer, or a JavaScript developer, or an AngularJS wizard. Nope. I’m a coder. A programmer. Pure, plain, and simple. Languages are just a tool and I happen to speak many of them. So, “Hello, World” and I hope you enjoyed the journey … here’s to the latest.

2013 — AngularJS

<div ng-app>

<div ng-init="greeting = 'Hello, World'">

{{greeting}}

</div>

</div>“Goodbye, reader.”

Related articles: